News • Responsive or not?

Breast cancer: Near-infrared light shows chemo beneficiaries

A new optical imaging system developed at Columbia University uses red and near-infrared light to identify breast cancer patients who will respond to chemotherapy.

There is currently no method that can predict treatment outcome of chemotherapy early on in treatment, so this is a major advance

Andreas Hielscher

The imaging system may be able to predict response to chemotherapy as early as two weeks after beginning treatment. Findings from a first pilot study of the new imaging system—a noninvasive method of measuring blood flow dynamics in response to a single breath hold—were published in Radiology.

The optical imaging system was developed in the laboratory of Andreas Hielscher, professor of biomedical engineering and electrical engineering at Columbia Engineering and professor of radiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “There is currently no method that can predict treatment outcome of chemotherapy early on in treatment, so this is a major advance,” says Hielscher, co-leader of the study, who is also a member of the Breast Cancer Program at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. His dynamic optical tomographic breast imaging system generates 3D images of both breasts simultaneously. The images enable the researchers to look at blood flow in the breasts, see how the vasculature changes, and how the blood interacts with the tumor. He adds, “This helps us distinguish malignant from healthy tissue and tells us how the tumor is responding to chemotherapy earlier than other imaging techniques can.”

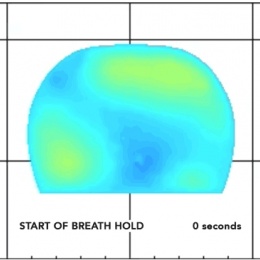

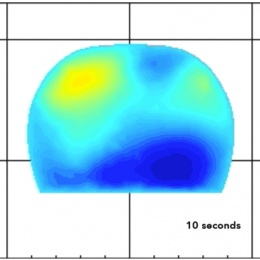

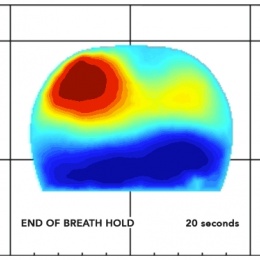

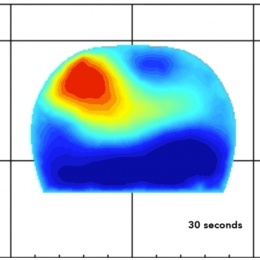

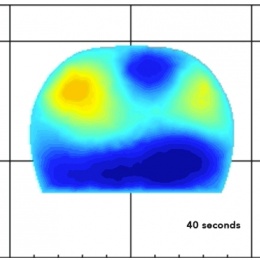

How the breast cancer optical system works. These series of images are cross sections of a breast with a tumor, taken during a breath hold. As a patient holds their breath, the blood concentration increases by up to 10% (seen in red). Researchers at Columbia found that analyzing the increase and decrease in blood concentrations inside a tumor could help them determine which patients would respond to chemotherapy. (Click images to enlarge)

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, given for five to six months before surgery, is the standard treatment for some women with newly diagnosed invasive, but operable, breast cancer. The aim of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is to eliminate active cancer cells—producing a complete response—before surgery. Those who achieve a complete response have a lower risk of cancer recurrence than those who do not. However, fewer than half of women treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy achieve a complete response. “Patients who respond to neoadjuvant chemotherapy have better outcomes than those who do not, so determining early in treatment who is going to be more likely to have a complete response is important,” says Dawn Hershman, MD, leader of the Breast Cancer Program at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia and co-leader of the study. “If we know early that a patient is not going to respond to the treatment they are getting, it may be possible to change treatment and avoid side effects.”

The researchers had suspected that looking at the vasculature system in breasts might hold a clue. Breast tumors have a denser network of blood vessels than those found in a healthy breast. Blood flows freely through healthy breasts, but in breasts with tumors, blood gets soaked up by the tumor, inhibiting blood flow. Chemotherapy drugs kill cancer cells, but they also affect the vasculature inside the tumor. The team thought they might be able to pick optical clues of these vascular changes, since blood is a strong absorber of light. The researchers analyzed imaging data from 34 patients with invasive breast cancer between June 2011 and March 2016. The patients comfortably positioned their breasts in the optical system, where, unlike mammograms, there was no compression.

This imaging system may allow us to personalize breast cancer treatment and offer the treatment that is most likely to benefit individual patients

Dawn Hershman

The investigators captured a series of images during a breath hold of at least 15 seconds, which inhibited the backflow of blood through the veins but not the inflow through the arteries. Additional images were captured after the breath was released, allowing the blood to flow out of the veins in the breasts. Images were obtained before and two weeks after starting chemotherapy. The researchers then compared the images with the patients’ outcomes after five months of chemotherapy. They found that various aspects of the blood inflow and outflow could be used to distinguish between patients who respond and those who do not respond to therapy. For example, the rate of blood outflow can be used to correctly identify responders in 92.3 percent of patients, while the initial increase of blood concentration inside the tumor can be used to identify non-responders in 90.5 percent of patients. “If we can confirm these results in the larger study that we are planning to begin soon, this imaging system may allow us to personalize breast cancer treatment and offer the treatment that is most likely to benefit individual patients,” says Hershman, who is also a professor of medicine and epidemiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Researchers are also studying other imaging technologies for breast cancer treatment monitoring, such as MRI, X-ray imaging, and ultrasound, but Hielscher notes that these have not yet shown as much promise as this new technology. “X-ray imaging uses damaging radiation and so is not well-suited for treatment monitoring, which requires imaging sessions every two to three weeks,” he says. “MRIs are expensive and take a long time, from 30-90 minutes, to perform. Because our system takes images in less than 10 minutes and uses harmless light, it can be performed more frequently than MRI.”

Hielscher and Hershman are currently refining and optimizing the imaging system and planning a larger, multicenter clinical trial. They hope to commercialize their technology in the next three to five years.

Source: Columbia University School of Engineering and Applied Science

12.02.2018