Article • Anti-infection strategies

Antibiotic stewardship programmes bear fruit

Today’s dilemma for hospitals and institutions are increasingly multi-resistant bacteria and decreasingly effective antibiotics to beat them. New substances to fight pathogens are not on the horizon. What can be done? Professor Constanze Wendt, microbiology and infection biology specialist at MVZ Labor Dr. Limbach & Kollegen GbR, in Heidelberg, Germany, describes current anti-infection strategies in German hospitals.

Antibiotic stewardship in clinical routine

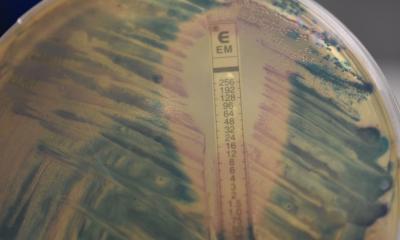

The German guideline to ensure rational use of antibiotics in a hospital, drafted in 2013, led to so-called antibiotic stewardship programmes being implemented in most hospitals. These programmes aim to optimise the use of antibiotics by appropriate selection, dosage, application and length of therapy, so as to slow down resistance development while maintaining best outcomes. For this purpose interdisciplinary hospital task forces have been established to collect and analyse internal data. They look at which antibiotics have been subscribed in what doses; which type of resistances occurs most frequently and which antibiotics can be used against what types of pathogens in a targeted fashion. Based on answers to those questions the task force can draft tailor-made therapy guidelines, taking into account the facility’s complexity, clinical disciplines and patient population. The results are promising. Even though a comprehensive evaluation still needs to be done, individual hospitals could reduce the use of antibiotics.

An interdisciplinary approach

The German guideline mandates specific structures and qualifications to implement the antibiotic stewardship programmes. In addition to microbiologists, infectiologists, hospital hygiene specialists and clinicians, each task force needs an antibiotic expert. The curriculum-based training is certified. ‘These preconditions demanded by the guideline need to be met before the task force can go ahead,’ Wendt explains. The professional associations, various medical associations and the German Society are offering this training programme for Hospital Hygiene.

Targeted therapy

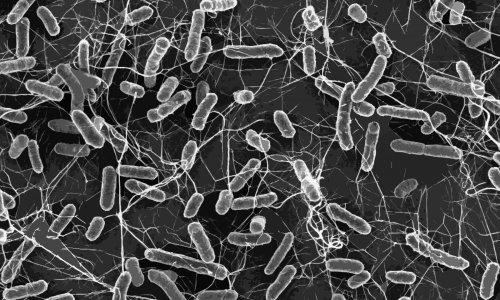

Standards developed in individual hospitals allow the physicians to target the therapies more precisely. Whereas patients frequently had received a broad-spectrum antibiotic, today the approach is far more differentiated. The data collected in-house show which bacteria are to be expected with which infection and which bacteria have turned out to be resistant. The selection of a medication is as ‘narrow’ as possible and as broad as necessary to provide the patient with an ideal therapy. Since samples are analysed in the lab to identify the bacterium, therapy can be adjusted if necessary after two or three days.

Hygiene

We are working on spreading the hygiene culture

Constanze Wendt

Strategies to combat bacteria include preventive hygiene measures. To avoid contagion, it is recommended that high-risk patients be washed with an antiseptic. Initial evaluations of this measure are underway but the current data do not yet warrant overall implementation. ‘Theoretically we all know what to do in terms of hygiene. Nevertheless, we are working on spreading the hygiene culture. While this sounds trivial it is in fact the most difficult task,’ Wendt points out. In general, hospital hygiene procedures are complied with; nevertheless, in times of staff shortages and extreme workload they may tend to be watered down. Thus multimodal training approaches are required that continue to drive home the issue and trigger sustainable behavioural changes. This involves presentations such as posters, role models, observation and feedback on hygiene behaviour as well as compliance checks – a long-term task, no doubt, but one with high chances for success as Wendt concludes: ‘With an infection rate of three to five percent we could increase safety to a very high level, since this translates to 95 percent of patients moving through the hospital without acquiring an infection.’

Research lags behind

For many years, antibiotics have been a very effective and fast therapy. Today, however, bacteria are developing resistance faster than research teams can develop new antibiotics. The situation is spiralling beyond control. Moreover, antibiotics launched in the past ten to twenty years contain hardly any truly innovative active ingredients. They were mostly modifications of existing drugs rather than entirely new ones – consequently the bacteria ‘knew’ them and could develop resistance even faster. Whilst many reasons exist for the lack of innovation, it is undisputed that the development of new drugs is time-consuming, fraught with setbacks and thus expensive. Professor Constanze Wendt warns: ‘We’re running out of time. There are only a few antibiotics left that we can use. It is crucial for us to develop new strategies.’

Profile:

With a Master of Science degree in Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health Professor Constanze Wendt MD is also a specialist physician for hygiene and environmental medicine as well as microbiology and infection epidemiology. As head of the hygiene department at Limbach Gruppe SE, MVZ Labor D. Limbach & Kollegen, in Heidelberg, Germany, with her team she advises hospitals, from primary to maximum care, as well as out-patient surgery centres, dialysis centres and rehabilitation facilities on all hygiene management issues.

15.06.2017