3-D mammography: Utilising eye to brain characteristics

Films with vivid 3-D images draw millions to cinemas – regardless of the plot. This technology, which is based on a stereoscopic effect, is not only entertaining but also medically relevant, as demonstrated by the Amulet three-dimensional digital mammography system produced by Fujifilm.

This technology also utilises particular characteristics of the human eye: the left and right perceiving the world from different angles. The two images coming together result in spatial representation – even if what is looked at is not three-dimensional.

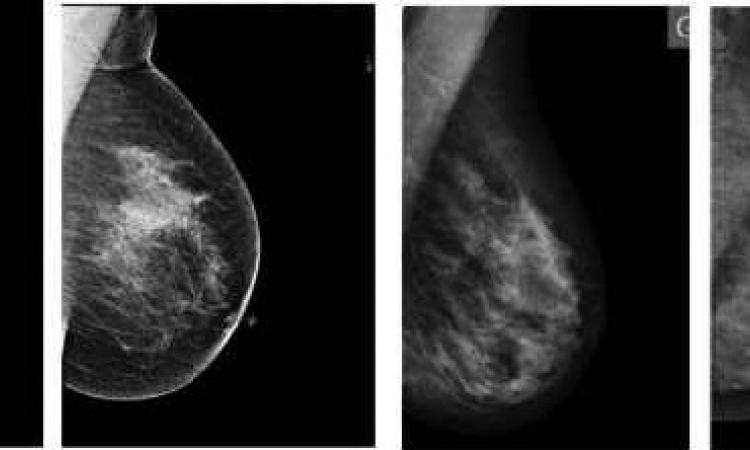

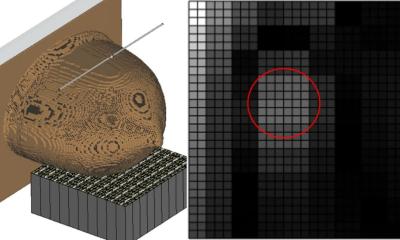

‘With the Amulet we produce images on two levels. However, we actually use a trick: after the first image is taken we immediately produce another one with the X-ray tube slanted by four degrees. Thanks to these second images we can produce three-dimensional images of the breast on the monitor,’ explains Dr Dirk Stoesser, from the Joint Practice for Radiology, Neuroradiology and Nuclear Medicine in Duisburg-Dinslaken, Germany. Since the beginning of 2011, Dr Stoesser and his colleagues have been among the first to trial the prototype of this innovative technology.

‘Real’ volume images of the breast are based on studies of at least 15 images and a wealth of information that streams together into a 3-D image on the monitor – in so-called 3-D tomosynthesis. ‘The biggest disadvantage of this approach is the high radiation dose required for imaging the volume. With the Fuji mammography equipment we generate this 3-D image with a dose of less than one millisievert,’ adds practice partner Dr Cord Neitzke.

The first image is taken with a dose rate of 70%, with the second image -- which is responsible for the 3-D effect -- only generating 30%. ‘Added together, the sum of the dose is about 10-15% lower than the national, average dose generated by a 2-D mammography image,’ Dr Stoesser explains.

With the current model special glasses, with different polarisation of light for each eye, are needed to view the images. However, in future models, it is expected that 3-D could become visible without glasses. Opportunities for characterisation and quantification are also to be adapted, allowing depth and volume measurements alongside distance measurements.

‘So far we have only been able to measure distance, but even this gives us an enormous diagnostic advantage compared to the 2-D view. In the case of dense breast tissue, the 2-D image makes it difficult to distinguish between a primary and a projection phenomenon. Moreover, the 3-D image makes it easier to see the outer limits of a primary growth,’ says Dr Neitzke, who views this as confirmation of the added value of this procedure for his practice, because, ‘Just as with every other new procedure there’s the important question as to whether false-positive, but especially also false-negative results, can be reduced -- and whether women will benefit from this. The recall rate must be lowered so that women do not become unnecessarily anxious.’

The assessments of 36 cases of breast cancer carried out by the Duisburg radiologists showed a statistically significant result, which confirms that the 3-D imaging procedure can help to reduce the rate of false-positive results significantly.

Both experts also see this development as a critical point for the mammography screening programme, the benefits of which, based on the latest studies, is now doubted. ‘Although imaging procedures are excellent, it is only conventional mammography that’s being covered by the programme. The budget does not even allow for an ultrasound scan. What this can lead to is something that we see here in curative mammography every day in the case of women who were screened half a year ago with no diagnosis, but who have now developed breast cancer,’ says Dr Stoesser, who would like to see enhanced reimbursement of costs in the context of the screening programme.

20.10.2011