Video • Wolbachia

Little-known bacteria might grind Zika and dengue infections to a halt

A Vanderbilt team took the next leap forward in using a little-known bacteria to stop the spread of deadly mosquito-borne viruses such as Zika and dengue.

Wolbachia are bacteria that occur widely in insects and, once they do, inhibit certain pathogenic viruses the insects carry. The problem with using Wolbachia broadly to protect humans is that the bacteria do not normally occur in mosquitoes that transmit Zika and dengue. So success in modifying mosquitoes relies on the bacteria’s cunning ability to spread like wildfire into mosquito populations. Wolbachia do so by hijacking the insect reproductive system in a process called cytoplasmic incompatibility, or CI. This makes the sperm of infected fathers lethal to eggs of uninfected mothers. However, if infected fathers mate with infected mothers, the eggs live, and the infected mothers carrying Wolbachia will also infect all her offspring with it. Then those offspring pass on Wolbachia to the next generation, and so on, until they eventually replace all of the resident mosquitoes. As Wolbachia spreads in the population, the risk of dengue and Zika virus transmission drops.

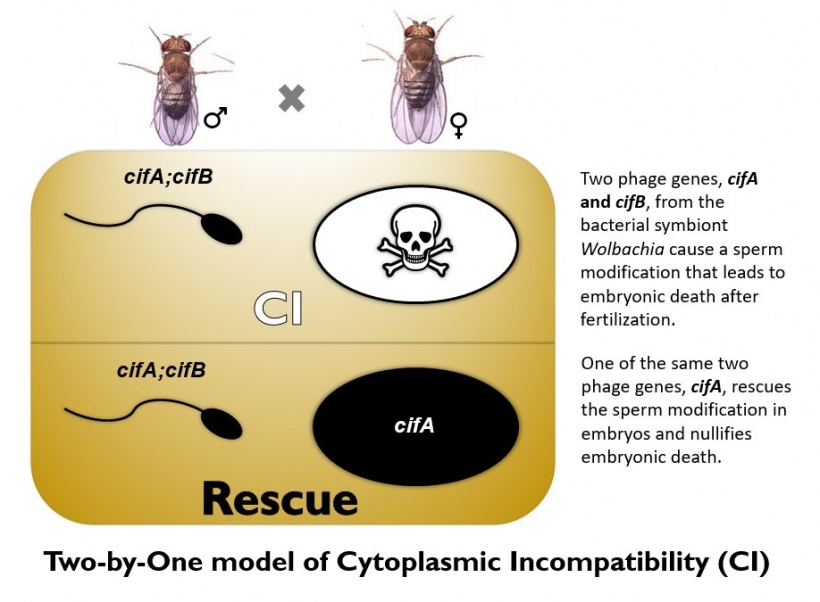

How that sperm and egg hijacking worked in infected fathers and mothers remained a mystery for decades, until Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Seth Bordenstein and his team helped solve it. They set out to dissect the number and types of genes that Wolbachia use to spread with the long-term goal of harnessing that genetic ability for protecting humans against diseases transmission. “In this new study, we’ve dissected a simple set of Wolbachia genes that replicate how Wolbachia change sperm and egg” Bordenstein said. “There are two genes that cause the incompatibility, and one of those same genes rescues the incompatibility. Engineering mosquitoes or Wolbachia for expression of these two genes could enhance or cause the spread of Wolbachia through target mosquito populations.” Their achievement is based on inserting genes into the genome of fruit flies. It is described in a paper appearing today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “A single prophage WO gene rescues cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila melanogaster.”

In a previous study last year, the team identified the two genes in Wolbachia — named cytoplasmic incompatibility factors cifA and cifB — and learned that they modify the sperm to kill eggs. Now they solved the other half of the genetic mystery: cifA single-handedly can protect embryos from death. “It’s a microbial encryption and de-encryptyion system that ensures Wolbachia spread through insect populations so they can adequately block the transmission of viruses and ultimately save lives” Bordenstein said.

Source: Vanderbilt University

24.04.2018