Article • Cancer Diagnostics

Liquid biopsies challenge imaging

Novel blood or urine tests can now detect a tumour and but might in future be able to say what type of cancer is developing in which organ.

Report: John Brosky

During the meeting of United European Gastroenterology, Sarah Bohndiek PhD was tasked with arguing against the rapidly emerging class of liquid biopsies that are challenging traditional imaging diagnostics techniques. But, she just couldn’t bring herself to do it. ‘Liquid biopsies are incredibly relevant,’ said Bohndiek, a Group Leader at the University of Cambridge, England, who, as a physicist, was expected to promote the merits of scanners over chemistry kits.

‘The evidence for these tests is building. The technologies are increasingly sensitive and there is evidence that, through epigenetics, we may even be able to work out the specific organ of origin,’ she said.

The term liquid biopsies covers an ever-widening number of diagnostic test kits, some using blood samples, others urine samples. Thanks to the convergence of powerful computer processing with the discoveries of genomic, proteomic and metabolomic biomarkers, these simple tests have the potential to identify a specific cancer and even stage the severity of tumour development.

There is a veritable gold rush underway as companies complete clinical phase testing of novel assays, including Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen Diagnostics and Genomic Health in the United States, MDxHealth based in Herstal, Belgium and Berlin-based Epigenomics.

In the pathology of colorectal cancer alone, a successful liquid biopsy test could capture a market opportunity estimated at US$2 billion. Bohndiek believes that, as these tests are likely to become more widely adopted for first-line screening than traditional diagnostics such as X-ray mammography, while using whole body imaging or endoscopy to detect tumors will become a second line of testing.

Shifting image for imagers

There are very long waiting lists at specialised centres

Sarah E Bohndiek

‘There will be a bit of a shift in how we see ourselves as imagers, perhaps the imaging community will see the advances of these liquid biopsies as an affront in coming years,’ she said. ‘Traditionally, we have been the go-to technology for early diagnostics in screening programmes, but I think it is likely that a liquid biopsy of some sort will become the go to technology.’

The benefit to healthcare systems will be cost savings as patients migrate from specialised centres back to the primary care setting where these tests can be administered.

For example, colorectal cancer screening using the gold standard of colonoscopy creates long queues of patients, especially in public payer systems, such as the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, she pointed out. ‘There are very long waiting lists at specialised centres, which is not very good if our goal is to detect cancer early.’

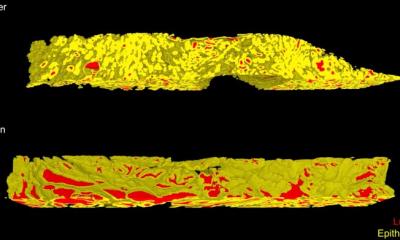

This is where the two diagnostics are complimentary and not competitive, she said, allowing a rapid movement for the patient through the pathway. Once disease is detected the role of imaging is to specifically the map the tumors, determine those with a high risk of progression, then guide interventions and monitor the effectiveness of treatment. About a third of the work in the Cambridge lab that Bohndiek directs is dedicated to developing endoscopic technology.

Profile:

With a doctorate in radiation physics and postdoctoral work in molecular imaging, Sarah E Bohndiek has led Cancer Research at the Cambridge Institute in the United Kingdom since 2014, working through the VISION Laboratory, also known as the ‘Bohndiek Lab’. In her own words, she describes her group as ‘a small, highly interactive and international research team, whose passion is using new technological innovations to improve our understanding of metabolic processes in disease. We hope to use these innovations to improve cancer patient survival, by finding routes to overcome drug resistance and eventually enabling earlier cancer detection.’

30.03.2017