Endovascular thrombolysis

Neurologists keenly debate the value of mechanical reopening of blocked blood vessels in the brain, as demonstrated during the 21st World Congress for Neurology (WCN) in Vienna this September. Theoretically, endovascular thrombolysis can only be considered for 20-30% of all incidents of stroke.

In reality, only 0.2% of stroke patients in Europe are treated endovascularly, as a study presented at the WCN by the EFNS Stroke Scientist Panel showed.

Mechanical blood clot removal comes with several options, as Professor Heinrich P Mattle MD, head of the University Clinic for Neurology at Bern University Hospital (Switzerland) explains: ‘The easiest and most successful method is thrombus aspiration with simultaneous proximal flow arrest. If this isn’t possible there are various instruments available to grab the blood clot and remove it. The most success with recanalisation can be achieved with retractable stent retrievers.’

A good argument for endovascular thrombolysis: In the case of large blood clots or proximal arterial occlusions, for example carotid T occlusion, standard treatment, i.e. intravenous thrombolysis, only rarely dissolves the blood clot and reopens the blood vessel. ‘In this situation there is a good chance of reopening the vessel with a stent retriever and to improve the patient’s condition,’ Prof. Mattle explains.

Following the first promising experiences with this innovative procedure, expectations were very high. However, recently the euphoria was a little dampened when results of studies published so far have not yet allowed clear recommendations. Prof. Mattle summarised the available data as follows: In the case of proximal occlusion of the middle cerebral artery, three randomised studies with pro-urokinase and urokinase have shown that endovascular pharmacological therapy is superior to placebo treatment.

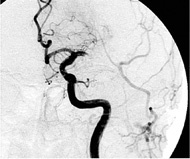

In a Swiss cohort comparison for media occlusions and a hyper-dense artery sign on the CT scan, endovascular therapy (Bern cohort) was superior to intravenous treatment (Zurich cohort). The outcome of a randomised study (synthesis expansion) was neutral, and showed neither superiority of the intravenous nor the endovascular treatment. However, more than half of the patients in synthesis expansion had suffered mild strokes, so are not in the target group for endovascular treatment.

Two further studies, IMS III and MR RESCUE, compared intravenous thrombolysis and the combination of endovascular therapy after intravenous therapy. Again, no difference in outcome was seen between the two treatments. On the one hand treatment was carried out at a late stage and, on the other, almost no stent retrievers were used. Furthermore, the DEFUSE-2 Study showed that an intervention is only advantageous for those patients whose scans showed a mismatch - and therefore cerebral tissue that can be saved. ‘Several further studies where stent retrievers are being used are currently on-going and in a few years’ time will hopefully bring more clarity as to which patients will benefit from endovascular treatment and which method benefits them the most,’ the Swiss neurologist points out.

In his lecture at the WCN, Prof. Mattle also answered the frequently asked question as to who is responsible for endovascular therapy: ‘It is important for the interventionist to have good knowledge of, and skills in, endovascular therapy not for stroke treatment alone, and that they can coil aneurysms and treat AVMs. Whether the interventionist initially specialised in neurology or radiology is of secondary importance – and some specialist associations create unnecessary barriers here. The most important thing is for the doctor to have good interventional skills and be carrying out these interventions frequently.’

‘At Bern University Hospital our well-rehearsed team, with neurologists and neuroradiologists as well as stroke nurses, MTRAs and anaesthetists, works really well,’ the professor emphasises. The neurologist carries out the initial treatment and the follow-on treatment and the neuroradiologist carries out imaging and the actual intervention. The indication for the procedure is jointly decided. ‘It is important that the treatment process, from emergency admission to imaging and intervention, as well as the follow-on treatment is organised and defined in a standardised manner.’

Profile:

Professor Heinrich Mattle MD is Senior Consultant and Assistant Director of the University Clinic for Neurology at Bern University Hospital, Switzerland. He also heads the Neurological Polyclinic and is co-head of the Stroke Unit and Neurovascular Laboratory at the hospital.

18.11.2013