Women in Radiology

Although Europe has many female paediatric and gastrointestinal radiologists, few women become interventional radiologists. Professor Malgorzata Szczerbo-Trojanowska is among that minority. When the former ECR President Professor Helen Carty retired from the congress, Prof. Szczerbo-Trojanowska became the only female Member of the Board of the European Congress of Radiology. Daniela Zimmermann, Executive Director of European Hospital journal, asked the professor about her choice of career and future prospects for women in this field

Member of the Board of the ECR Professor Malgorzata Szczerbo-Trojanowska, is Chairman of the Department of Radiology and Head of the Department of Interventional Radiology, at the University Medical School, in Lublin, Poland. The professor has carried out research in Italy, the UK, Sweden and Germany and is a member of many Polish radiological organisations, as well as the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe and the International College of Angiology. 172 of her papers, and 11 monographs, have been published in scientific journals

Women radiologists are not rare in Poland, Professor Szczerbo-Trojanowska explained. ‘They became interested in the field many years ago, when only X-ray machines were available. Due to the X-ray exposure, the job description stipulated shorter hours and two weeks extra holiday time. Today, given advances in equipment, and therefore reduced X-ray exposure, I expect, and hope for changes because, many radiologists who work those short hours opportunistically seek additional jobs elsewhere.’

Are women radiologists well accepted by male counterparts in Poland, or are they perceived as a potential threat?

‘Those who achieve a high standard in their practice or performance are fully accepted. They are so very much involved in the profession that they don’t want to compete with the men, or take their places. However, there are quite a number of women in leading positions - as heads of departments and chairs of societies,’ she pointed out, adding: ‘However only few women chose interventional radiology. Being an interventional radiologist, is hard work. You have to stay in the operating theatre or cath-lab for many hours, wearing heavy aprons, mask and cap. So it is a stressful, hard job.’

For a year before becoming the only woman ECR Board Member, she had enjoyed the presence of the former ECR President Professor Helen Carty. ‘Professor Carty’s professionalism was so high that there wasn’t a single problem that could arise because she’s a woman. If you want to compete with a man you must be a good radiologist and an open minded, tolerant person. Professor Carty has such a great personality that she managed the Board and complex European issues smoothly. I really admired the way she ran the ECR Board as its chairman. She was very diplomatic, and absolutely excellent. It’s probably something I could not achieve. She had another advantage: we use the English language for discussions. If that’s your mother tongue you can be very precise and sometimes when things are very difficult you need a lot of diplomacy to find the right word to express thoughts, or a way to argue with someone, so as not to offend him. Professor Carty had a very delicate way of convincing opponents. Also, I think women generally are more tender, cautious, delicate and diplomatic than men. Along with diplomacy they pay more attention to details, because excellency is made of small details. Men will often go straight forward, not caring about particulars. This may lead to failures,’ she pointed out.

Does Professor Szczerbo-Trojanowska want to become ECR President?

‘Ambitions always run high. We say: If you go step by step then you gain an appetite. But you should develop a way of waiting and looking and talking to people and to make your way slowly. Some individuals are driven by too high ambitions, I favour modesty and criticism in modulation of ambitions. I am convinced that success of ECR should come before ambitions of an individual. Quite early on, in Poland, I became head of a department, and then quite soon took a chair of radiology at the university where I work. Then I had the great honour and pleasure to be the first woman to become president of the Polish Radiological Society, It all happened in a natural way. I suppose I did not compete with the men, but I was simply promoted higher and higher step by step. I gained experience in being in a society, working first on a Board, then in various sections, then becoming chairman of small sections, and so on. And I had a few new ideas. I had observed my society for many years and thought it is time to change many things - the statutes, for example - which a lot of people actually wanted, because my election occurred along with the political and economic changes in Poland. Traditionally, the presidents served two terms up to 6 years, so a society did not develop as quickly as it should. The first year is for running in, the second you have to do something, but then, if you are to be routinely re-elected, you think there’s no need to make a big effort. So I introduced changes; one was to have no re-election. The president has one term and knows that it is the only period he or she can contribute to the society, introduce new ideas. Then someone else takes over.

‘I succeeded with most of my ideas. We changed a lot of paragraphs in our statutes. I convinced most of the Board Members that it was a good way to change a society. For example, we changed our journal, quickly. In one year an old-fashioned journal became a very modern one. We also radically changed our education system, radiology specialisation and examination. So, in a short time, many things occurred that convinced people that this was a good direction in which to proceed. I was not forcing the changes - I had the feeling that almost 100 percent of the board wanted and supported changes, and everyone came up with their own ideas. It was time to become up-to-date.’

The ECR is of course very different from a national society. It deals with radiologists in the diverse countries of Europe. ‘For many years, especially before we changed our system, we knew that countries such as Poland and Hungary could not have adequate presence in European radiology, due to politics and economics. Europe was divided,’ the professor observed. ‘Since most countries are now joined in one Europe I thought it would be easier for radiologist from Eastern countries to appear on the scene, but I thought this process would be quicker. At the ECR there are not enough moderators of sessions or members of sub-committees from East European countries; most are from Western Europe. I’ve had lots of discussions with presidents and Board Members about this, and was told that nominations come from sub-committees and sub-specialisation societies.

Obviously for years scientists from Western countries were well known. But when I looked at statistics I found that for example the number of abstracts accepted from Poland ranked in the first ten countries with highest contribution, but it did not correspond with the involvement as moderators or sub-committee members.

As a member of the Board I feel it is my responsibility to stress existence and potential of Central and East European radiology. I am convinced that their increased involvement will strengthen ECR.

Asked whether radiologists in Poland must become more management oriented as in other EU countries, the professor explained that the healthcare system has not changed that much in her country in the last few years. ‘We have a domination of the national health care. Private services are growing but still very limited. Private insurance is planned for the future. Procedures in my department are paid via national healthcare insurance, and their number is strictly limited. You may have limit of a hundred procedures a month, but there are 150 to do. That’s a problem. It can be dramatic, because I must decide whether to do a certain procedure for a patient immediately or place him on a waiting list. This is a very uncomfortable situation.’

Has she ever considered a political career?

‘Definitely not! However my position in the Polish Society was in a way political. We had meetings in the Ministry of Health, and that’s how we tried to improve radiological services. We wrote a lot of letters and reports on current situation. We were pointing to the necessity of establishing standards of radiology in various departments, in big and small cities.

The professor points out to the Health Minister many of the standards and ideas operating in European countries. ‘I say: “Have a look. We should follow those well functioning solutions”. These are the arguments used, she said. ‘However, up to now, the consequences are not satisfactory. But if we make at least some steps in the right direction, progress will come. In ten years we could not reach the same level of solutions as Western Europe. We not only needed to change the system of politics and economics, but also people’s mentality, because fifty years in Eastern Block covers more than one generation. So it will take time, but it will come.’

What does she consider the most exciting radiological development today?

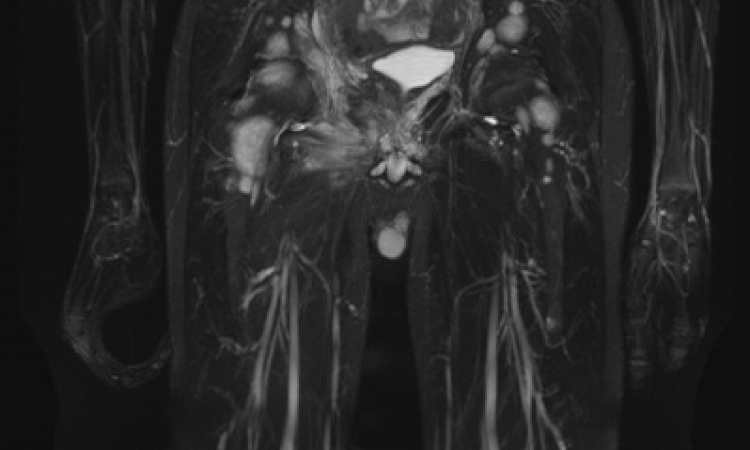

‘Molecular imaging, because present imaging reached anatomical and morphological accuracy close to that of anatomy lab. It means that again radiology will go beyond typically diagnostic imaging of organs to cellular and functional imaging, having a major impact on medicine in future. Radiology will again push the development of treatment. We did not expect this years ago.

‘Interventional radiology, introduced by vascular radiologists, promoted radiology into treatment. We can now offer attractive alternatives to surgical interventions and completely new therapeutic solutions. I think radiology is at the moment one of the most exciting specialities.’

Finally, we asked why the professor had chosen this field, since initially she had hoped to become a surgeon, because her father was one. ‘When I married a neurosurgeon the thought of one more surgeon in the family led me elsewhere,’ she replied. Inspired by a tutor who had a vision that interventional radiology would flourish in the future, the professor said she realised this field was a little akin to surgery and felt she had found the right compromise. I also felt I would have more contact with patients than other radiologists.’

In 1970, at Lublin’s Medical University, she qualified with distinction as a physician, and in 1976 gained her PhD and became a Board Certified specialist in diagnostic radiology. In 1977 she became an assistant professor at the Department of Interventional Radiology, University Hospital Lublin.

How did her father react to her work?

‘When I told him in early seventies that it is better to do a percutaneous nephrostomy rather than an open nephrostomy, he asked: How could you puncture a renal pelvis through the kidney, just percutaneously, just under fluoroscopy? You should open it, he said, you should take a look. Then he said: Try it! He was very impressed when we did the first nephrostomy and it worked.

Now aged 58 years, the professor reflected: ‘My father and husband have always been supportive, because, as a radiologist I provided diagnoses to neurosurgeons - and now we even co-operate closely, because I treat patients with vascular lesions of the brain, such as aneurysms, AVM’s, percutaneously, doing embolisations. So the number of the patients who have open surgery to clip an aneurysm is decreasing, but we can propose the best treatment option for each patient.’

Does her intensive work plus society and political involvements encroach on her family life?

‘It’s impossible for a doctor to close the hospital door and stop thinking about patients. There are many difficult cases to think about every day, day and night,’ Professor Szczerbo-Trojanowska observed. ‘However, being a family of two doctors makes it easier to understand each other and easier to accept that a telephone call in the night means one of them has to leave home to treat an urgent case. It has also been accepted by my two sons.’

02.08.2006