Surgery

Virtual Reality helps in surgical planning

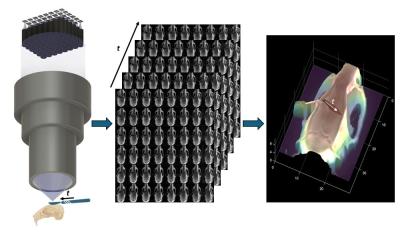

Before an operation, surgeons have to obtain the most precise image possible of the anatomical structures of the part of the body undergoing surgery. University of Basel researchers have now developed a technology that uses computed tomography data to generate a three-dimensional image in real time for use in a virtual environment.

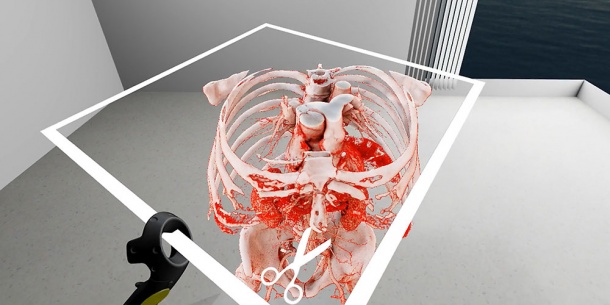

The planning of a surgical procedure is an essential part of successful treatment. To determine how best to carry out procedures and where to make an incision, surgeons need to obtain as realistic an image as possible of anatomical structures such as bones, blood vessels, and tissues.

Researchers from the University and University Hospital of Basel’s Department of Biomedical Engineering have now succeeded in taking two-dimensional cross-sections from computer tomography and converting them for use in a virtual environment without a time lag. Using sophisticated programming and the latest graphics cards, the team led by Professor Philippe C. Cattin succeeded in speeding up the volume rendering to reach the necessary frame rate. In addition, the SpectoVive system can perform fluid shadow rendering, which is important for creating a realistic impression of depth.

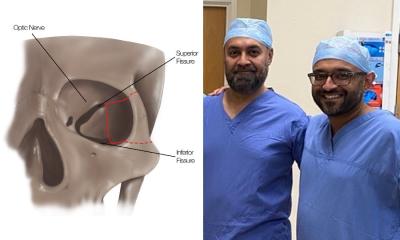

For example, doctors can use the latest generation of virtual reality glasses to interact in a three-dimensional space with a hip bone that requires surgery, zooming in on the bone, viewing it from any desired angle, adjusting the lighting angle, and switching between the 3D view and regular CT images. Professor Cattin explains the overall benefits: “Virtual reality offers the doctor a very intuitive way to obtain a visual overview and understand what is possible.”

“This brand-new technology smoothly blurs the boundary between the physical world and computer simulation. As a doctor, I am no longer restricted to looking at my patient’s images from a bird’s eye view. Instead, I become part of the image and can move around in digital worlds to prepare myself, as a surgeon, for an operation in detail never seen before,” says ophthalmologist Dr. Peter Maloca.

“I have found that these new environments continue to guide me and have helped rewire my senses, ultimately making me a better doctor. Those who stand to gain the most here are doctors, their patients, and students – all of whom can share in this new information,” adds Maloca, who works at University Hospital Basel’s OCTlab and at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London.

Source: University of Basel

21.12.2016