Article • prenatal diagnostics

Ultrasound is indispensable in prenatal exams

‘In prenatal diagnostics, particularly in the first trimester, ultrasound continues to be the modality of choice when looking for malformations,’ says Professor Markus Hoopmann, deputy director of prenatal medicine and gynaecological ultrasound at the Women’s Health Clinic in Tübingen University Hospital. This case for ultrasound is significant because today fetal DNA that circulates in the maternal blood, can be screened for trisomy 21, or Down’s syndrome. ‘When this blood test was introduced, many experts predicted the demise of prenatal screening, particularly in the first trimester.’ He strongly rejects a swansong.

The trisomy 21 blood test offers 99 percent sensitivity. A success rate, Hoopmann concedes, ultrasound first trimester screening will never achieve. Nevertheless, he adds, ‘many people forget that the cell-free fetal DNA test is a screening test, not a diagnostic test. For a full diagnostic work-up representative fetal cells are needed that can only be obtained by punction.’

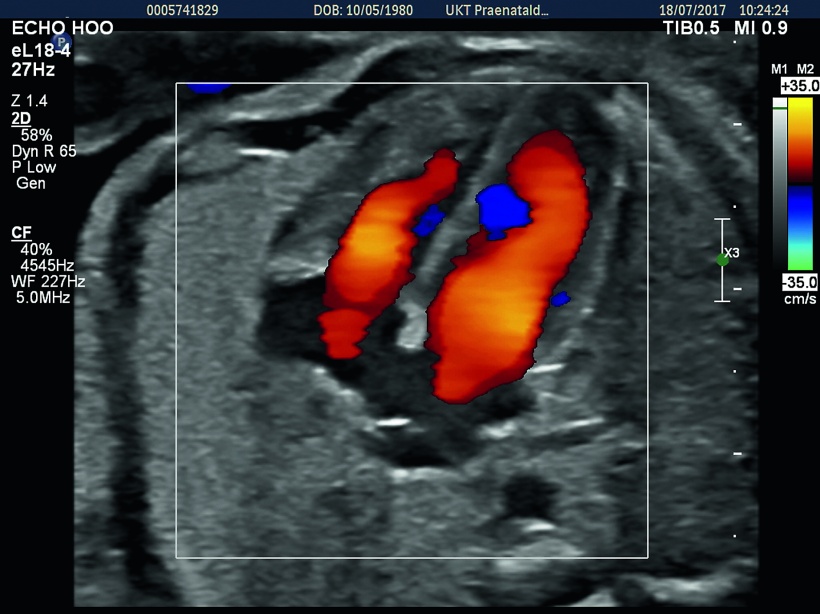

However, an even more important misconception is the widely held view that trisomy 21 screening equals prenatal diagnostics. ‘Chromosomal anomalies account for a mere 10 percent of all malformations – and of those 10 percent only half are trisomy 21,’ he explains. Far more frequent are structural anomalies, such as congenital malformations of the heart, anenzephaly or holoprosencephaly. ‘50 percent are clearly visible in ultrasound during the first trimester. Today, even spina bifida can be detected much better due to specific changes in the posterior fossa: Modern ultrasound systems offer increasing resolution which means that more and more anatomical detail is visible.’

Another alleged or real innovation in ultrasound that he is not keen on, especially in prenatal diagnostics, is artificial intelligence, inter alia in automated nuchal translucency measurement: ‘Automated measuring processes by no means replace quality assurance.’ The positioning of the measuring points to measure fluid in the neck at 11-13 weeks pregnancy is not crucial but correct setting of the planes on the ultrasound system. ‘Deviating only a few degrees can significantly compromise your results. The sagittal plane has to be set manually,’ Hoopmann explains, In prenatal ultrasound diagnostics, ‘at no point is a human body, from the little finger to the mitral valve, examined more thoroughly and in its entirety as in the first trimester.

‘No machine can handle this complexity. But maybe I’m just not as utopia-inclined as other people.’

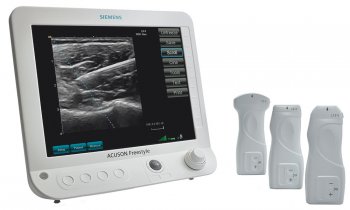

3-D ultrasound is another issue where Hoopmann’s feet are firmly on the ground: ‘So far all endeavours to establish 3-D prenatal ultrasound as a superior method have failed.’ He does about 95 percent of his diagnoses on 2-D images. Nevertheless, he says, 3-D can be helpful in certain cases, for example in the evaluation of cerebellar vermis. For a few weeks now, Hoopmann has been using an innovative transducer, the eL18-4 by Philips, which does offer the desired results. ‘This transducer delivers best resolution in first trimester exams with abdominal access,’ he reports.

Older linear probes tend to lack penetration. Albeit, the new transducer also has its limitations: as soon as a foetus is larger than 8 cm it becomes difficult to generate a whole-body image. Thus, this particular probe can play out its strengths during the first trimester when the foetus is still small.

Profile

Since 2006, gynaecologist/obstetrician Markus Hoopmann MD has focused on specialised obstetrics and perinatal medicine and chaired the working group Ultrasound Diagnostics in Gynaecology/Obstetrics (ARGUS). In 2009, he became deputy director of prenatal medicine and gynaecological ultrasound at the Women’s Health Clinic, University Hospital Tübingen, Germany. This April he was appointed extraordinary professor at Eberhard Karl University Tübingen.

03.11.2017