Pediatrics

Technology reveals fetal brain activity

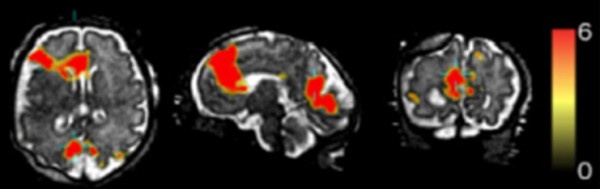

NIBIB-funded researchers at the University of Washington have pioneered an approach to image functional activity in the brains of individual fetuses, allowing a better look at how functional networks within the brain develop. The work addresses a common problem of functional MRI; if the subject moves during the scanning, the images get distorted.

By creating a way to correct for motion, the team was able to make a four-dimensional reconstruction of brain activity in moving subjects, opening the door for studies on subjects that don’t stay still for long, like fetuses and small children. The new strategy enables investigations into both normal brain development and the effects of a mother’s diet or environment on the functional development of the fetal brain.

The new work focused on the default mode network—a collection of regions that are active when the brain is at rest, when someone is daydreaming or letting their mind wander, not concentrating on a specific task. Fetal brains are in default mode for much of the time, but it is not very well known how this network develops.

“This is one of the first papers to take individual fetuses and look at the naturally developing default mode network in the human fetal brain,” says Vinay Pai, Ph.D., director of the Division of Health Informatics Technologies at NIBIB. Since movement of the baby or the mother is no longer an issue, “It allows you to look at more natural developmental stages.”

In the new study researchers aimed to create a four-dimensional movie of fetal default mode network activity. To do this, they used functional MRI—a technique that detects brain activity based on blood flow; active regions have higher levels of blood flowing to them. Besides blurring the image, the problem with movement—either from the fetus moving or the mother’s breathing—is that it shifts the focus, making it hard to locate where any signals of activity are coming from. While typically just one measurement is collected for each position at each time point, the team collected multiple measurements, each providing slightly different perspectives. Using the multiple measurements, they were able to reposition the images to create an estimate of what the activation over a period of a few minutes would look like.

The team first tested their method on adults by telling them to purposely move their head in the scanner. After showing they could successfully quantify brain activity in moving subjects, they then scanned eight fetuses between 32 and 37 weeks of pregnancy, as infants born prematurely at that age have been shown to have active default mode networks. The resulting images were compiled to create a four-dimensional view of each of the brains over a five-minute time window.

“It really hasn’t been explored when these activity networks—these collections of brain areas that start to work together in the brain—emerge and what types of cells and tissues they emerge in,” says Colin Studholme, Ph.D., a professor with joint appointments in pediatrics and bioengineering at the University of Washington and senior author of the paper. “What this is leading to is not just collecting data from individual babies but also understanding and building a four-dimensional map of brain activity and how it should emerge in a normal baby.”

The technique can also be used to compare differences in brain development in premature and full-term babies; the effects of alcohol, drug use, or stress during pregnancy; or if there are any prenatal differences in babies that go on to develop neurodevelopmental disorders like autism. And it is not restricted to imaging the brain; Studholme also plans to study the placenta and how its development influences the brain.

But the immediate application—for squirmy babies—is promising in itself. “Techniques that minimize the effect of motion resolve a lot of problems,” says Pai. “In fetal imaging, you don’t have too many options.”

Source: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering

19.10.2016