Image source: Pexels/Pranidchakan Boonrom

News • The hidden 'fingerprint' of liver cirrhosis

Routine blood tests could be key to stopping 'silent killer'

New research has shown that results of blood tests routinely performed by GPs everywhere contain a hidden fingerprint that can identify people silently developing potentially fatal liver cirrhosis.

The researchers have developed an algorithm to detect this fingerprint that could be freely installed on any clinical computer, making this a low-cost way for GPs to carry out large scale screening using patient data they already hold.

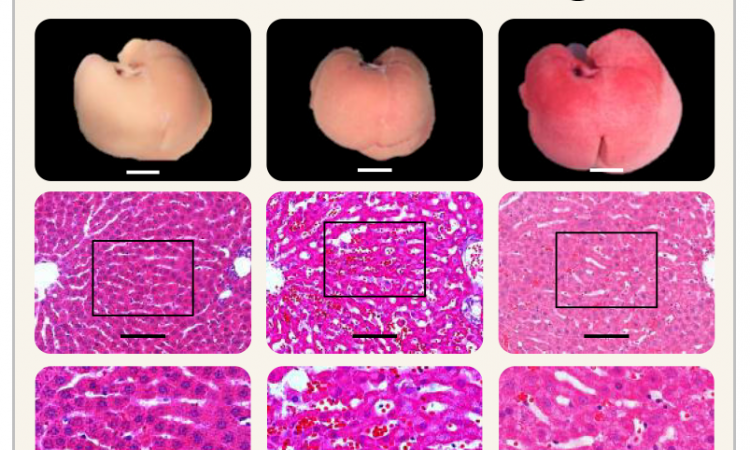

Liver cirrhosis is the second leading disease causing premature death in working-age people (after heart disease). It develops silently and most patients will have no signs or symptoms until they experience a serious medical emergency and the first admission is fatal in one in three patients. Unlike most major diseases, the mortality rate for liver cirrhosis continues to increase and is now four times higher than forty years ago.

In this new study, published in the journal BMJ Open, a team of researchers developed the CIRRUS algorithm (CIRRhosis Using Standard tests) which they then used to analyse anonymised NHS data on blood test results taken in primary and secondary care for nearly 600,000 patients. The algorithm was able to pick up over 70% of people with cirrhosis, months or years before they had their first emergency admission with liver disease. The accuracy rate of the test was around 90%.

In most cases the data needed to find these patients already exists and we could give patients the information they need to change their lifestyle

Nick Sheron

The research was led by Professor Nick Sheron of the Foundation for Liver Research, who started the study whilst working at the University of Southampton. Prof Sheron said: “More than 80% of liver cirrhosis deaths are linked to alcohol or obesity, and are potentially preventable. However, the process of developing liver cirrhosis is silent and often completely unsuspected by GPs. In 90% of these patients, the liver blood test that is performed is normal, and so liver disease is often excluded. This new CIRRUS algorithm can find a fingerprint for cirrhosis in the common blood tests done routinely by GPs. In most cases the data needed to find these patients already exists and we could give patients the information they need to change their lifestyle. Even at this late stage, if people address the cause by stopping drinking alcohol or reducing their weight, the liver can still recover.”

Pamela Healy OBE, Chief Executive of the British Liver Trust said, “The UK is facing a liver disease crisis. Three quarters of people are diagnosed at a late stage when it is often too late for treatment of intervention yet liver disease does not get the same attention as the other major killers such as heart disease and diabetes. We are delighted to support this important study that could dramatically improve early detection rates. The challenge now is to ensure that early detection is embedded in NHS practice.”

Co-author Michael Moore, Professor of Primary Health Care Research at the University of Southampton added, “Whilst we are all preoccupied with the coronavirus pandemic we must not lose sight of other potentially preventable causes of death and serious illness. This test using routine blood test data available, gives us the opportunity to pick up serious liver disease earlier which might prevent future emergency admission to hospital and serious ill health.”

Recommended article

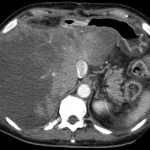

Interview • Diffuse liver diseases

The liver is a master of deception

Professor Dr Thomas Kröncke, Medical Director of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology at Klinikum Augsburg, has been dealing with liver diseases for 17 years. Talking to European Hospital he explains which diseases the liver tends to mask and why fatty liver has become a public health issue.

If implemented, the research team believe that the algorithm could be used in two ways. Firstly, incorporating it within existing GP systems could flag up warnings on an individual basis as tests are carried out. Secondly, a scan could be run across all patient data and those identified as being at risk would be invited back to the surgery for a confirmatory test. Teresa Hydes from the University of Southampton who was also part of the research team added, “This test is free in many cases as a large proportion of UK adults will have already had a blood test at some point which would provide enough data to run the CIRRUS algorithm. The algorithm is freely available to GP practices or networks to install and therefore offers a low cost way to identify at risk individuals without using up limited NHS time and resources.”

Professor Sheron concluded, “Liver cirrhosis is a silent killer, the tests used most by GPs are not picking up the right people, and too many people are dying preventable deaths. We looked at half a million anonymous records and the data we needed to run CIRRUS was already there in 96% of the people who went on to have a first liver admission. With just a small change in the way we handle this data it should be possible to intervene in time to prevent many of these unnecessary deaths.”

Prof Guruprasad Aithal, President, British Association for the Study of the Liver, commented: “In a proportion of people who are overweight, have diabetes or drink alcohol in excess, liver scarring builds up without any symptoms. Even when there is advanced liver scarring, the problem is often picked up too late only when liver fails. Prof Nick Sheron and colleagues have developed an algorithm using routine blood tests, which can pick up liver scarring well ahead of time before it leads to liver failure. This means that ‘alerts’ can be set up whenever blood tests are done to identify those who are on the path of progressive liver damage. Early recognition helps to put in place help to prevent future health problems.”

Dr Steven Masson, Alcohol Lead at British Society of Gastroenterology and Consultant Hepatologist at Freeman Hospital, Newcastle, said: “The BSG has been advocating for the development of tools which help identify and detect those with alcohol-related harm, particularly liver disease, at an earlier stage. Therefore, this tool, which uses blood tests which are readily available and routinely measured in primary care, has huge potential clinical utility. Unfortunately, currently most people with alcohol-related liver disease are identified late, as its remains silent until complications of portal hypertension or liver failure develop, when mortality is high. This month, the ONS report that the alcohol-specific death rate reached its highest peak in 2020 (since the data series began in 2001). The impetus for early detection, intervention and/or referral to specialist services has therefore never been greater.”

Dr Richard Piper – Chief Executive , Alcohol Change, added: “Alcohol harm is so much more extensive that most of us believe – causing untold damage to individuals, families, communities and wider society. But the good news is that it is completely avoidable. Alcohol-related liver diseases are far and away the most significant cause of alcohol-specific deaths, yet currently the vast majority of people find out that their liver is diseased way too late. What is needed is a reliable means of alerting doctors and their patients to potential liver disease as early possible. The CIRRUS process shows real promise and we want to see it further developed, tested and implemented, to help to save hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of lives.”

Source: University of Southampton

01.04.2021