© Charité/Frauke Schreiber

News • Focus on ILC immune cells

Research reveals cause for lupus kidney damage

A team led by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, German Rheumatology Research Center (DRFZ) and Max Delbrück Center have defined key cells behind severe kidney damage in lupus.

The research, published in Nature, could inform future antibody therapies.

A Berlin-led research team has uncovered critical regulators of severe kidney damage in patients with lupus, an autoimmune disorder affecting an estimated five million people worldwide, most of which are young women. A small, specialized population of immune cells – called innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) – trigger an avalanche of effects that cause harmful kidney inflammation, also known as lupus nephritis.

These ILCs are really amplifiers in this system. They are small in population, but they seem to fertilize the whole process

Andreas Diefenbach

The research upends conventional wisdom that attributes the main hallmarks of lupus nephritis primarily to autoantibodies, which mistakenly attack healthy tissues. “While autoantibodies are required for tissue damage, they are by themselves not sufficient. Our work reveals that ILCs are required to amplify the organ damage,” says Dr. Masatoshi Kanda, one of the three senior paper authors who was a Humboldt Fellow at Max Delbrück Center and is now at the Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Sapporo Medical University in Japan.

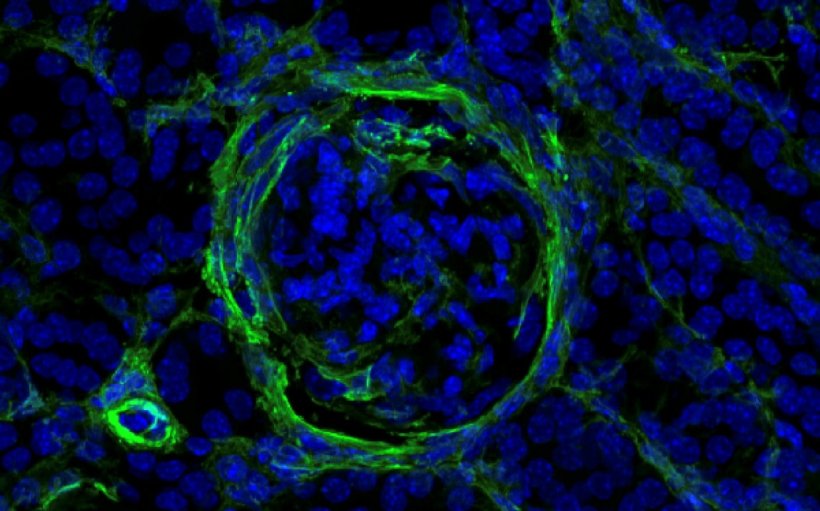

Lupus, technically called systemic lupus erythematosus, is most often diagnosed in women between the ages of 15 and 45. Symptoms can range from mild to severe. But what causes some patients to develop kidney damage – some to the point of requiring dialysis – while others do not, has been unclear. “The role of ILCs in lupus or lupus nephritis was entirely unknown,” says Prof. Antigoni Triantafyllopoulou, a senior paper author at Charité’s Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology and Liaison Group Leader at the DRFZ, an institute of the Leibniz Association. “We have now identified most of the circuit controlled by ILCs by looking at the whole kidney at single-cell resolution.”

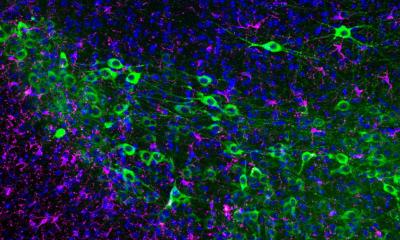

ILCs are a small group of immune cells that live in a specific tissue or organ. “They are in the tissue all the time, from the time of embryonic development, which makes them very different from other immune cells that circulate throughout the body,” says Prof. Andreas Diefenbach, a senior paper author and director of the Institute of Microbiology, Infectious Diseases and Immunology at Charité. Diefenbach’s lab was among those that discovered ILCs in the mid-2000s. Most of his research is focused on ILCs in the gut and how they modify tissue function. In this study, Triantafyllopoulou and Kanda teamed up with his group and Dr. Mir-Farzin Mashreghi at the DRFZ to find out whether ILCs were present in the kidney and what role they might play in lupus nephritis.

To unravel this mystery, the team turned to single-cell RNA sequencing, which reveals what single cells are doing by identifying genes that are turned up or down. Often in immunology, researchers focus on particular immune cell types of interest. This team took a much broader approach, sequencing nearly 100,000 individual kidney and immune cells of various types and functions for this project. Kanda developed a specialized protocol for single-cell RNA sequencing of mouse and human kidneys. “Masatoshi’s protocol was very good at pulling out and preserving multiple types of kidney cells, which gave us a much more complete overview of how lupus affects the whole kidney,” explains Triantafyllopoulou.

Through many experiments, the team learned that a subgroup of ILCs with a receptor called NKp46 must be present and activated to cause lupus nephritis. When NKp46 is activated, this subgroup ramped up production of a protein called GM-CSF, which stimulates growth of invading macrophages. Macrophages are large immune cells that gobble up dying cells and microbes. In the kidney, a flood of incoming macrophages caused severe tissue damage and buildup of scar tissue, called fibrosis. “These ILCs are really amplifiers in this system,” Diefenbach says. “They are small in population, but they seem to fertilize the whole process.”

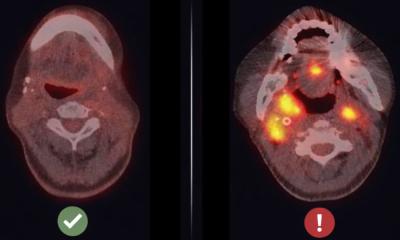

When the team blocked NKp46 with antibodies or the receptor was genetically removed, kidney tissue damage was minimal. They also blocked GM-CSF with similar anti-inflammatory effects. “Critically, autoantibody levels did not change when NKp46 was inhibited, but kidney tissue damage was reduced, which shows autoantibodies are not directly responsible for kidney inflammation,” Triantafyllopoulou explains.

Much of the work was done in mouse models because it is very difficult to conduct this type of mechanistic study in people, especially when it involves experimental antibodies that have not been approved for human use. The team compared the results to sequencing data from human patients with lupus and found ILCs present, though more work is required to fully understand how to target ILCs in human kidneys. The insights gained through these detailed studies pave the way for the development of new antibody therapies for patients with severe forms of lupus, with the aim of preventing the need for kidney dialysis.

Source: Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

17.08.2024