News • Contamination

Painful knee prosthesis: loose, infected or both?

The implantation of knee and hip joints is considered one of the success stories of recent years. But periprosthetic joints infections (PJI) are one of the severe complications, with an infection rate of 2%. The probability of revision surgery increases with concomitant diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, with fracture prosthesis or after previous surgery.

Report: Beate Wagner

Topical treatment with antibiotics is becoming increasingly important.

Professor Georg Matziolis MD

The challenges in diagnosis include low-grade infections, small colony variants, contamination of samples, mixed-species colonisation and increasing development of resistance: Apart from MRSA the other problematic pathogens include gram-negative bacteria (MRGN) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE).

Treatment is impacted by old age and multimorbidity. ‘Often, high concentrated antibiotics cannot be administered,’ says Professor Georg Matziolis MD, Senior Consultant at the Clinic for Orthopaedics and Emergency Surgery at the Eisenberg Waldkrankenhaus. ‘Topical treatment with antibiotics is becoming increasingly important.’

‘Firstly, it is important to establish whether a PJI or aseptic loosening is present,’ explains Professor Johannes Holinka MD, from the Medical University of Vienna. In 25% of cases a PJI is the reason for revision and, in 16%, it’s mechanical loosening.’ The anamnesis, followed by radiological and clinical examination along with laboratory diagnosis of blood, synovial fluid, tissue and histology provide the indications required.

Microbial detection as the primary objective of the diagnosis of low-grade infections often proves difficult. ‘In up to 30% of cases no micro-organism can be cultivated,’ Holinka points out. The specificity of microbiological cultures increases with the number of samples. ‘Three to six intraoperative samples are ideal, and in cases of low virulence organisms or after previous administration of antibiotics we require up to ten.’

Sonification is more significant than a tissue culture. As a biomarker, Alpha-defensin facilitates the detection of a PJI because it is not impacted by antibiotics. Quantitative measurements have shown a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 97% respectively. The procedure only has one disadvantage: ‘Although the diagnosis is as good as certain it does not provide microbial detection,’ Holinka says. On the other hand, Multiplex-PCR (mPCR) of synovial fluid with Unyvero ITI for instance is often decisive for treatment.

‘The analysis can be carried out with minimal effort and with no need for specialist staff trained in molecular biology or a special infrastructure,’ he adds. ‘Microbial detection including resistance markers is available after five hours, even for low virulence organisms that normally take 14 days to cultivate.’ Combined with the culture grown, the sensitivity is around 90%.

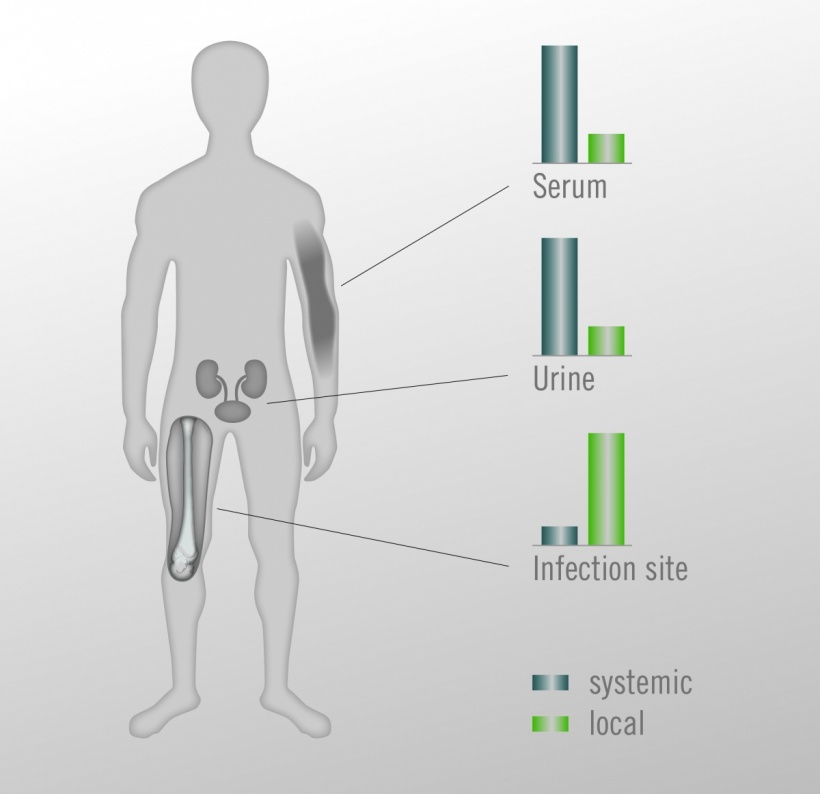

Treatment of a PJI is carried out via one- or two-stage revision and high-dose antibiotics. With an eradication rate of 89.2% and 90.6% respectively the effectiveness of both procedures is very close. ‘Successful one-stage exchange requires microbial confirmation, radical debridement and effective antibiosis with systemically and locally applied antibiotics,’ says Dr Akos Zahar, orthopaedic specialist at the Helios Endo-Klinik, in Hamburg. The key to success for the one-stage procedure lies in the close multidisciplinary cooperation between surgery, microbiology and infectiology. ‘For one-stage exchange the use of industrially manufactured, antibiotic-loaded bone cement (such as Copal G+C or Copal G+V) is recommended to achieve the high concentrations required for local antibiotics therapy without actually having to add antibiotics yourself. ‘This avoids turning the doctor into a manufacturer of medical products,’ the expert underlines. With cemented one-stage exchange, antibiotical treatment can be cut from several weeks to 14 days.

Two-stage exchange is the gold standard worldwide. This is indicated in cases of negative bacterial culture, difficult-to-treat pathogens as well as in the case of soft tissue defects that require a step-by-step approach. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement is used as a spacer during the prosthetic-free interval and for the re-implantation during the second operation. ‘Dynamic spacers (such as those made from Copal knee moulds) are more effective than static ones,’ Zahar points out. ‘They offer more patient comfort, are easier to re-implant and the functionality is better,’ adds Matziolis.

Dynamic spacers (...) are more effective than static ones. They offer more patient comfort, are easier to re-implant and the functionality is better.

Dr. Akos Zahar

The abrasion of cement and ceramics particles appears clinically irrelevant. There is currently little evidence available for mobile spacers compared to static spacers. However, the advantages of mobile spacers for dead space management and local antibiotics treatment prevail. Two meta-analyses have shown that the range of motion (ROM) for the mobile spacer is better by +8 degrees. It is also superior regarding lower re-infection rates, reduced bone loss and easier re-implantation.

Matziolis talked about the superiority of spacers made from industrially manufactured, antibiotic-loaded bone cement compared to alternatives with antibiotics added manually. The release rate of the antibiotics gentamicin and clindamycin from a spacer made with industrially manufactured bone cement (Copal G+C) is higher at all points in time.

The team around Mike Reed at Northumbria Health Care (UK) confirmed a reduction of infections with the use of antibiotic-loaded cement in the prosthetic care of femoral neck fractures in a randomised examination. The study proves that dosage and release are decisive. Standard cement (Palacos R+G) was compared to high dose dual antibiotic cement (Copal G+C). The reduction in the infection rate for deep-lying infections was 3.5% with Palacos R+G; for Copal G+C it was only 1.1%.

15.12.2016