Image courtesy of Tyler Van Buren, University of Delaware

News • Hemolysis monitoring

Measuring blood damage in real-time

Scientists at the University of Delaware and Princeton University have developed a method to monitor blood damage in real-time.

“Our goal was to find a method that could detect red blood cell damage without the need for lab sample testing,” said Tyler Van Buren, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Delaware with expertise in fluid dynamics. The researchers recently reported their technique in Scientific Reports, a Nature publication.

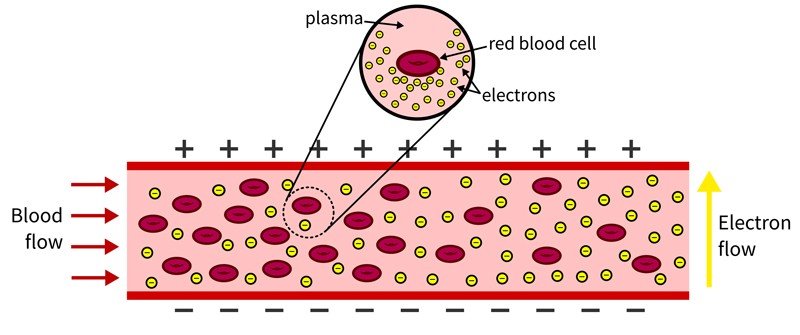

In the body, red blood cells float in plasma alongside white blood cells and platelets. The plasma is naturally conductive and is efficient at passing an electric charge. Red blood cells are chock-full of hemoglobin, an oxygen-transporting protein, that also is conductive. This hemoglobin is typically insulated from the body by the cell lining. But as red blood cells rupture, hemoglobin is released into the bloodstream, causing the blood to become more conductive. “Think of the blood like a river and red blood cells like water balloons in that river,” said Van Buren. “If you have electrons (negatively charged particles) waiting to cross the river, it is more difficult when there are a lot of water balloons present. This is because the rubber is insulated, so the blood will be less conductive. As the water balloons (or blood cells) break, there are fewer barriers and the blood becomes more conductive, making it easier for electrons to move from one side to the other.”

We are not doctors, we’re mechanical engineers. This technique would need a lot more vetting before being applied in a clinical setting.

Tyler Van Buren

In dialysis, a patient’s blood is removed from the body, cleaned, then recirculated into the body. The researchers developed a simple experiment to see if they could measure the blood’s mechanical resistance outside of the body. To test their technique, the researchers circulated healthy blood through the laboratory system and gradually introduced mechanically damaged blood to see if it would change the conductive nature of the fluid in the system. It did. The researchers saw a direct correlation between the conductivity of the fluid in the system and the amount of damaged blood included in the sample.

While this issue of damaged blood is very rare, the research team’s method does introduce one potential way to indirectly monitor blood damage in the body during dialysis. The researchers theorize that if clinicians were able to monitor the resistance of a patient’s blood going into a dialysis machine and coming out, and they saw a major change in resistance — or conductivity — there is good reason to believe the blood is being damaged. “We are not doctors, we’re mechanical engineers,” said Van Buren. “This technique would need a lot more vetting before being applied in a clinical setting.” For example, Van Buren said the method wouldn’t necessarily work across patient populations because an individual’s blood conductivity is just that, individual.

In the future, Van Buren said it would be interesting to evaluate whether conductivity also could be used in place of lab sampling for applications outside of dialysis. For example, this might be useful in research aimed at understanding how blood cells may be damaged, both inside and outside of the body, and possible methods for prevention. He also is curious whether this method could be used to evaluate and identify compromised blood samples on-site, saving time and money for hospitals or diagnostic laboratories, while eliminating the need for patients to make multiple trips to have blood drawn if there is a problem.

Source: University of Delaware

23.05.2020