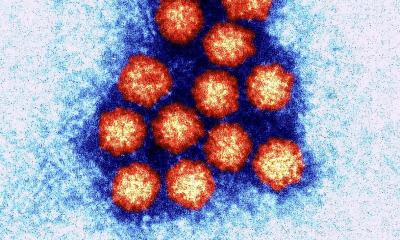

Investigating the HFN1 virus

Dutch virologist Ron Fouchier and his colleagues around the world stopped their research into the bird flu virus H5N1 for a whole year to allow an international debate surrounding the benefits and risks of their work.

Since mid-February, Dr Fouchier and team, who work in the high security laboratories at the Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam, have resumed their research into the transferability of the virus to mammals. The international influenza research community is agreed that these studies are rightful and important, he emphasised during the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Society for Virology in Kiel, Germany. During this meeting in early March 2013, around 1,000 participants, mostly from Germany, Austria and Switzerland, discussed current findings and developments in the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of viral infectious diseases. Dr Fouchier’s research was among the key topics.

The hosting Society for Virology, the largest scientific society in Europe in this field, supported the re-uptake of research into the transferability of the H5N1 virus in principle, confirmed the society’s President Professor Thomas Mertens, medical director at the Institute of Virology, University Hospital Ulm. ‘We are convinced that the scientific findings and social benefit of such studies outweigh the risk of danger, assuming adherence to the appropriate safety precautions are adhered.’

By introducing the H5N1 bird-flu virus to lab ferrets, the Dutch team studied which mutations need to be present in order for mammals (or humans) to contract the virus. Unlike the swine flu virus H1N1, which caused a worldwide pandemic in 2009, H5N1 is not transferable from human to human. However, there is no guarantee that it will remain so: ‘We know that flu viruses jump from animal species to humans on average every 20 years,’ Dr Fouchier said, during a European Hospital discussion. ‘And, every time this happens they acquire the ability to become airborne.’

Precisely how that change – which is decisive for transmission – occurs as yet is completely unclear. This knowledge would be a prerequisite for the ability to identify dangerous types of viruses and to fight their transmission systematically. These findings would also be valuable for the development of vaccines and medication – making the respective studies also of great importance for hospitals, Dr Fouchier pointed out. ‘If we ever see a pandemic with a virus like H5N1, clinical management will rely on laboratory experiments like those we did.’ Incidentally, the question is not if but when the next pandemic will occur and how severe it could be, said the scientist, who is considered to be one of the world’s leading experts on highly pathogenic influenza viruses.

‘Maybe next time we are not as lucky as we were in 2009.’ The trigger for the controversy that caused Dr Fouchier and colleagues to interrupt their research into the H5N1 virus early in 2012 was an evaluation by the US National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB), which advised Science magazine against publishing Dr Fouchier’s research findings in their entirety. Allegedly, there was a danger that terrorists could use this knowledge to create a ‘killer virus’ for use as a biological weapon. This then unique event alarmed the media as well as the political world. Dr Fouchier himself has often explained that he considers the NSABB’s position on this matter wrong. On one hand the ‘reproduction’ of an H5N1 virus, which may possibly be able to reproduce in human hosts, and to trigger a pandemic, would require solid, specialist knowledge.

On the other hand, numerous viruses occur naturally and they could lead to fatalities at a higher rate of transmission. The lack of publication led to the controversy, which has not always been professionally handled. ‘Since we were not allowed to disclose details of our work and explain the benefits, the only thing left to discuss was risk.’ Meanwhile, the findings have now been published. The safety of the laboratories at the Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam was never officially doubted, Dr Fouchier pointed out. Therefore, there was also no need for any changes before research in to the H5N1 virus resumed. ‘Our laboratories were specifically designed for this work; they were already extremely safe and well secured. Scientists working there have very extensive training and are re-evaluated for their knowledge and ability to respond to incidents every year.’

In addition to the license from the responsible Dutch ministry, the safety of the facilities is also checked by the US government, which finances the research. In the Netherlands the study’s publication will have legal reper cussions. A court will investigate whether the work could indeed be perceived as an instruction for the creation of biological weapons. If the judges share this view, each individual EU government would be given the option to censor scientific work at will, Dr Fouchier fears.

PROFILE

In 2012, Time Magazine listed Dr Ron Fouchier among the 100 most influential people. In the Department of Virology at Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam his research focuses on the evolution and molecular biology of respiratory viruses in humans and animals, with special emphasis on influenza virus zoonoses and pandemics and hMPV. In 1995, Dr Fouchier received his PhD in Medicine at the University of Amsterdam for his studies on molecular determinants of HIV-1 phenotype variability at the Department of Clinical Viro-immunology, Sanquin Research. From 1995-1998 he was a post-doctoral fellow at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia, where he studied the function of the HIV-1 Vif protein and nuclear transport of HIV-1 pre-integration complexes. Subsequently he set up a new group at Erasmus MC to study the molecular biology of respiratory viruses, particularly the influenza A virus. As a fellow of The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, he studied influenza virus zoonoses and pathogenicity. Recent achievements of his team include the identification and characterisation of several ‘new’ viruses; the human metapneumovirus (hMPV), a human coronavirus (hCoV-NL), the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and a new influenza A virus subtype (H16).

22.05.2013