Interventional procedures relieve pain in pleural effusion

In a Special Focus Session, experts addressed the necessity to perform palliative interventional techniques in cancer treatment and they insisted that interventional radiologists should become more than just technicians.

All images provided by Prof. Afshin Gangi from Strasbourg Hospital, France.

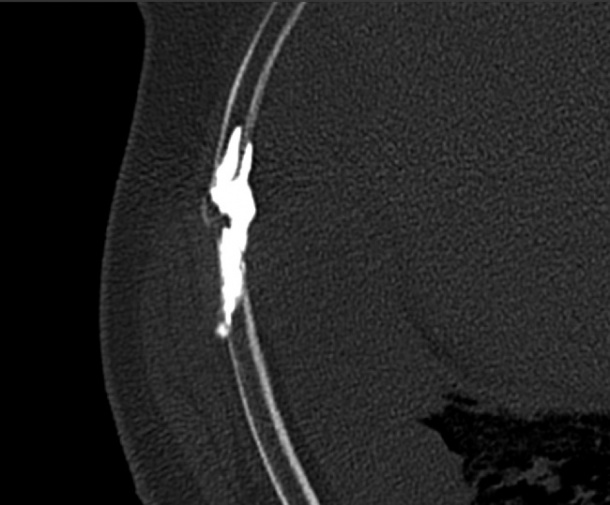

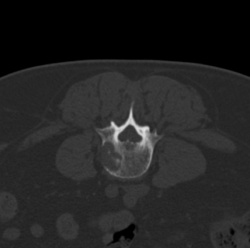

Prof. Afshin Gangi, an interventional radiologist from Strasbourg Hospital, France, focused on cementoplasty during the session’s first lecture. Cementoplasty is a procedure indicated for painful, lytic bone metastasis especially when there is a risk of compression fracture in the spine, condyles or acetabulum. The procedure consists of injecting acrylic cement or glue directly into lytic bone metastasis. With cementoplasty, interventional radiologists can control pain and consolidate bone, but they cannot treat the tumour.

Gangi explained how and when to use cementoplasty, a technique he believes should be considered in the context of the whole patient. “Patients need to be seen before and after the procedures and interventional radiologists need to be responsible for the patient from A to Z. The patient is not just a metastasis,” he said. Cementoplasty may be performed after an ablation. It must always be considered alongside other anti-cancer therapies and techniques when planning a patient’s disease management.

Gangi also focused on the broader aspects of disease management in his talk. He insisted on the need for interventional radiologists to be more than technicians. They need to be complete clinicians, and this is currently a weakness of interventional radiology, he believes.

Patients referred for cementoplasty are usually under the care of a chain of clinicians and sometimes certain treatment options can be overlooked due to a lack of communication between the links in the chain. Patients with renal cell carcinoma and bone metastases exemplify this scenario. The pain and fragility of these metastases can be treated with cement but they continue to grow very quickly inside the spinal canal causing paraplegia. “Here you need to consolidate the vertebral body to treat pain and then use therapy to control the tumour too,” Gangi recommended.

Another talk, by Prof. Fergus Gleeson, a radiologist working at Churchill Hospital, Headington, Oxford, U.K., focused on issues around the management of pleural effusions, highlighting ways of managing pleural effusion in patients. Gleeson explained that a cancer, whether inside or outside the chest, can be associated with pleural fluid either by direct invasion or by seeding along the surface that creates fluid.

“Palliative care aims to treat symptoms, most notably breathlessness. Patients can also present with pleural effusion when a cancer has not been diagnosed. Often the first symptom of cancer in these patients is breathlessness caused by pleural effusion. Symptoms are the same whether the patient presents de novo or has a known cancer,” he said.

Diagnosis of pleural effusions can be made by sampling pleural fluid and this method provides a diagnosis of malignancy in 60 percent of patients, Gleeson said. In the other 40 percent, and also in patients with mesothelioma, there is less fluid, and the number of cases where the cause of the pleural effusion has been diagnosed may be as low as 30 percent.

Gleeson recommends a simple chest x-ray to diagnose pleural effusion, and then an ultrasound scan to locate the fluid and remove it, followed by a CT scan to determine if the effusion is due to cancer including its extent and primary source. He will also address an ongoing debate about the number of fluid removals required for a reliable diagnosis, and whether medical thoracoscopy should be used to determine malignancy in addition to tissue biopsy.

10.03.2013