In the era of Big Data radiology is left behind

There is a wealth of information in every radiology exam, but even a phalanx of super-computers at the National Security Agency (NSA) could not extract it.

There is a wealth of information in every radiology exam, but even a phalanx of super-computers at the National Security Agency (NSA) could not extract it.

Image by courtesy of IBM

Referring physicians, and even other radiologists, have a hard time figuring out if a given report is positive or negative. ‘If all a radiologist did at the end of the report was to say if it was positive or negative for the reason it was done in the first place, that would be a major advance in radiology archives,’ said Eliot Siegel MD, Chief of Imaging at Veterans Affairs Maryland Healthcare and Director of the Maryland Imaging Research and Technologies Lab.

‘Every time we do an examination, for example for CT pulmonary angiography, when we issue a report saying we do not see any pulmonary emboli, we are not including hundreds of different types of data that we could include for computer algorithms to be able to discover in the future,’ he told French radiologists at the Sixth Computed Tomography Symposium (Nancy, France).

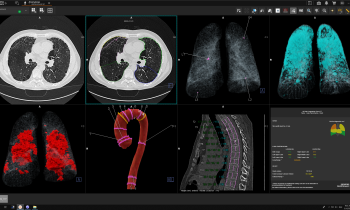

During a single-shot thoracic scan that takes a few seconds, the CT captures images that can be converted to quantifiable data for lung nodules, breast masses and calcifications, cardiac chamber size, aortic size, coronary artery calcifications, rib fractures, liver texture, lung texture, bone mineral density, loss of height of vertebral bodies, renal function and renal volume.

In an ideal world, the raw data set from this scan would be stored with meta tags and automated mark-up language, making it discoverable for current health policy information or future research.This data could also be shared locally among other support systems in a hospital for treating patients. Instead, once the radiology report is issued, the data is irretrievably lost, ironically the very moment it is sent to cloud storage.

‘We radiologists need to reinvent ourselves,’ Dr Siegel emphasised. ‘If radiology is going to be important, then just as with lab and genomic data, we need to make our data discoverable, indexed and tagged.’

Much is at stake, starting with incomes earned by radiologists or approvals of capital equipment expenditures for new equipment.

In the United States, he suggested, as the concept of Meaningful Use becomes more sophisticated, healthcare administrators are going to impose reimbursement for a radiology exam based on providing to the healthcare system basic, discoverable types of information.

‘In the era of Big Data, people are looking for benefits and outcomes they can prove with data,’ he pointed out. ‘If we can’t give answers to basic questions, we cannot demonstrate the value of the data in radiology. It’s going to become increasingly difficult for radiologists to get reimbursement and funding if people cannot find the data that’s hidden inside our scans, and even inside our reports.

‘What we issue are reports that are analogue in a digital age. It is essentially a tweet that responds to a specific question; but, unlike a tweet, it is not in a form that can be recognised by a computer.’

If loss of income from hospital administrators is not a sufficient driver to move radiologists to structured reporting, then perhaps armies of liability lawyers can help.

Currently, radiologists often make recommendations, such as a follow-up exam. Yet there is no way of knowing if the referring physician read the report or acted on the findings. ‘Radiologists make recommendations all the time but practically no one in radiology follows up to see if the recommendations have been carried out,’ Dr Siegel explained. ‘Legally, the radiologist is held accountable for the recommendations where there are untoward consequences or adverse events, such as a tumour that grows. Courts have an expectation that recommendations have been carried out.’

Closing the communications loop with digital information input to automated systems would improve the ability to track liability associated with error and could accelerate the movement to structured reporting. Eliot Siegel has been out on the leading edge of radiology for 30 years, advocating change for a profession firmly entrenched for 100 years in a tradition of providing consultative free text interpretations of images. In the 1980s he created the world’s first filmless, digital radiology archive for the VA system in Maryland. ‘The entire storage capacity we had was one terabyte and it cost us $800,000, the same terabyte capacity I can buy today at any Best Buy store for $45,’ he said.

He was responsible for the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Cancer Image Archive and served as Workspace Lead for the caBIG In Vivo Imaging Workspace.

At radiology events, such as the one in Nancy, he pushes for adoption of the Annotation and Image Markup (AIM) developed by NCI that creates a single standard format to store computer-discoverable image annotations.

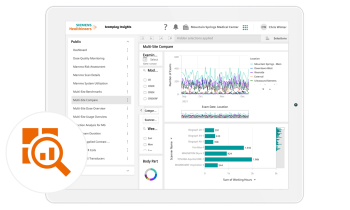

He also preaches a vision that speaks to the potential of radiology information joining the full power of Big Data. A first advance would be receiving responses to queries in seconds, not days, he said.

Increasingly, pixel interpretation of structures could be compared and matched with other biomedical information, leading to a definition of imaging biomarkers for disease and its progression.

Yet, he sees the true potential in fulfilling the greater promise of personalised medicine, where a patient’s imaging can be assigned, cross-referenced and correlated with genomic or histological data, and compared to similar cases to make predictions on treatment and outcomes.

06.03.2014