EASD 2010 review

Meike Lerner reports

7,000 people from 120 countries met in Stockholm this September to hear international experts discuss the progress, solutions and challenges of one of our greatest healthcare burdens. Prevention, self-monitoring, surgery, guidelines, economic problems, drug-safety, and co-morbidities – these are just a few of the problems associated with the care of about 55 million diabetics in Europe.

Diabetic care consumes up to 10% of healthcare budgets – rising to over 18.5% in some countries (Source: International Diabetes Federation, Diabetes Atlas, 4th edition. 2009). However, despite huge scientific and other efforts to tackle the problem, a report funded by the European Commission, coordinated by EURADIA -- a unique alliance that advocates increased diabetes research in Europe -- found a significant deficit in the level of diabetes research funding across the EU. The estimated research sum is €500,000,000. The estimated spend on diabetic care is an astounding €50 billion -- annually. These figures, as well as a comprehensive strategy for European diabetes research, were presented during EASD by DIAMAP - a project funded under Framework Programme 7.

DIAMAP – a roadmap for research and a coordinated research platform

If adopted by European funding organisations and researchers, DIAMAP will help to improve treatments for both type 1 and type 2 diabetics; it will also produce the first online resource (www.DIAMAP.eu) for funders and scientists to view potential areas of collaboration, skills and resources among other diabetes research teams.

During the report presentation, the DIAMAP coordinator, Professor Philippe Halban, said: ‘Europe has historical strength in diabetes research, but such expertise is underexploited through lack of vision, poor coordination and inadequate funding. The major outcomes of this road map strategy will be to ensure that research is focused on the individual with diabetes, leading to improved treatment and prevention of this devastating disease. Research would be coordinated to exploit regional expertise in particular and improve competitiveness. Funding would need to be in proportion to the costs of the disease, with closer collaboration between academia and industry. DIAMAP is a battle plan to combat the diabetes crisis. If there is no significant increase in research investment, the numbers of people with diabetes will continue to rise and become increasingly costly, especially in younger people, for whom the impact of complications is even more devastating with a correspondingly greater impact on the economy.’

Drug development guidelines: Reducing cardiovascular risk

The case of Avandia, the diabetes drug recently banned from European pharmacies by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), reveals another huge topic to be finally tackled: the safety aspects in the development of new diabetes drugs. Avandia, a real diabetes blockbuster from GlaxoSmithKline, was suspected of significantly increasing the risk of heart attacks for a long time before the EMA stopped the drug’s use (September). According to the British Medical Journal, reporting at the beginning of that month, the first hints that the benefit of Avandia could not be sufficiently proved had already appeared during the accreditation phase in 1999. In 2007, a first study indicated the risk of a heart attack. The problem was that accreditation studies showed that HbA1c could be reduced by 1%, but the long-term consequences had not been considered.

To improve drug safety, at the beginning of 2010, the EMA published draft guidelines on clinical investigation of medicinal products to treat diabetes mellitus. Those guidelines were issued and commented on by the EASD Panel on Global statements, which was presented at the congress. In particular, the EMA wish to ensure that add-on and combination studies compare against established agents and that there is robust analysis of success based on therapeutic targets, non-responders and hard outcomes.

The EASD welcomes the consideration on safety aspects of new drugs and its requirement for cardiovascular outcomes and long-term safety to be assessed. It is of note that both major cardiovascular events and other major events, including heart failure, must be evaluated. The EMA’s position is that a reduction of insulinaemia, or insulin dose, can be of clinical interest but is not considered a sufficient measure of efficacy unless accompanied by a favourable evolution of HbA1c. For future developments, the research programme undertaken by pharmaceutical companies should provide sufficient data to support the lack of a drug-induced excess cardiovascular risk, from both a clinical and a regulatory perspective. In this respect, the EMA requires studies on patients with an over five-year diabetes duration, and an analysis of outcomes in those with microvascular and/or macrovascular complications.

Measuring, educating and treating diabetics

The congress symposia and exhibition underlined massive efforts undertaken to improve quality of life for diabetics from several directions. We can present just a few:

Sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy

A long-term and large, randomised, controlled study of sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy in type 1 diabetes showed that patients using this type of technology (Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm Real-Time System) achieved better glucose control without an increase in hypoglycaemia, compared to multiple daily insulin injections. The STAR 3 trial (Sensor-Augmented Pump Therapy for A1C Reduction) data also shows a statistically significant reduction in glycated haemoglobin (A1c) levels. The reduction of the A1c levels was four times greater than the multiple daily injection (MDI) group (0.8% vs.0.2%). The mean decrease was from a baseline of 8.3% to 7.5% in the sensor-augmented pump therapy group, compared to only 8.3% to 8.1% in the MDI group. In addition, for the adult participants, there was a full 1% reduction of the A1c levels.Every percentage point drop in A1c can reduce the risk of microvascular complications by 40%.

New systems for insulin delivery: ‘patch-pumps’ and artificial pancreas

Focusing on Engineering the future of Diabetes Care: from Insulin Pumps to Nanomedicine, during the Eli Lilly Symposium, John Pickup, Professor of Diabetes and Metabolism at King's College London School of Medicine, Guy’s Hospital, UK, said that a major impact in improving diabetes care lies in three areas: insulin delivery, glucose sensing and attempts to build an artificial pancreas. Whereas insulin pumps are already known to be beneficial in Type 1 diabetes, new ‘patch-pumps’ are likely to be smaller, more convenient, and may open up insulin therapy to selected type 2 diabetics. However, present uptake of insulin pump therapy varies and, in the future, needs to be more widely available throughout the world.

A partially closed-loop system connecting continuous glucose monitoring to an insulin pump has already entered clinical practice, whereby basal insulin delivery is automatically suspended for up to two hours if glucose falls below a hypoglycaemic threshold.

The barrier to a safe, effective, fully artificial pancreas for everyday use is considered to be the present lack of a sufficiently reliable and accurate glucose sensor. ‘We are researching a new generation of glucose sensors, based on glucose-induced changes in fluorescence lifetime, rather than electrochemistry. Glucose sensors, using a glucose receptor based on engineered bacterial glucose-binding protein labelled with an environmentally sensitive fluorosphore, can be encapsulated in nano-engineered membranes, for potential implantation in the skin or, alternatively, incorporated in a fibre optic probe for monitoring of subcutaneous interstitial glucose concentrations. The long term aim is to use this technology to engineer an artificial pancreas.’

Structured self-monitoring of blood glucose

William H Polonsky PhD, Associate Clinical Professor in Psychiatry, Behavioural Diabetes Institute, University of California, San Diego, and principal investigator of the STeP study (Structured Testing Protocol) presented the results of an expanded self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG). The aim of the 12 month prospective randomised, multi-centre study was to determine whether the use of the Accu-Chek 360 View Blood Glucose Analysis System, a novel SMBG data collection tool from Roche, can positively influence glycaemic control when used as part of a comprehensive intervention in which primary care physicians and patients work collaboratively to address glycaemic abnormalities. Indeed, it could be shown that the use of this new diabetes management concept, including structured SMBG, data visualisation, pattern analysis and derived therapy adjustments, can significantly contribute to a reduction of HbA1c values and improved glycaemic control in non-insulin treated type 2 diabetics and, at the same time, help to reduce diabetes-specific psychological distress and depression levels.

SMBG needs to be tailored for diabetics

According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) guidelines, ‘SMBG should be considered because it is currently the most practical method for monitoring post-meal glycaemia.’ However, during a Bayer Healthcare conference, Professor Oliver Schnell, of the Diabetes Research Group at the Helmholtz Centre in Munich, reported and acknowledged that SMBG protocols should be individualised to address each diabetic’s specific educational, behavioural and clinical needs. ‘The optimal intensity and frequency of SMBG protocols depend on a variety of factors, such as the type of diabetes, chosen therapy options, individually set target ranges for the long-term marker HbA1c indicating the average blood glucose level over a period of weeks or month, as well as pre- and postprandial results. Therefore, SMBG is an effective strategy but needs to be complemented by treatment approaches tailored to patients.´

Innovative blood glucose meters offering meal-marker functions, integrated software and different levels of personalisation definitely support those aims, but as Professor Louis Monnier, of the Laboratoire de Nutrition Humaine Institut, Universitaire de Recherche Clinique, in Montpellier, France, stressed: ‘Given the relatively high costs of SMBG, it would be remiss to ignore the economic implications of SMBG. The potential benefits of SMBG must therefore be balanced against its costs, especially when such expenditure may come at the expense of other treatment modalities.’

To provide an adapted diabetes education, healthcare providers are therefore eager to gain better understanding of their patients needs. Recent studies show a significant relationship between existing information gaps, motivational deficits and limitations with regard to behavioural skills and the reported frequency of SMBG. ‘Patients often show poor motivation to measure their values regularly if testing is not explained sufficiently, or meters, strips or lancets are not reimbursed by the healthcare system,’ Prof. Monnier said. ‘SMBG is an effective tool and essential for people with diabetes to obtain accurate blood sugar results, but gaining the full benefit from it takes knowledge, skills and willingness.’

Diabetes nurse Magdalena Annersten Gershater, from the Department of Endocrinology at University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden, has daily experience of the challenges involved in diabetic education. By offering psychological support, expert advice and guidance, she empowers patients to take over the decision-making role and control their disease in a self-determined way. ‘By evaluating individual requirements, such as the level of knowledge and education, as well as analysing problems perceived by the patients on a physical, psychological or social level, diabetes educators approach existing, underlying conditions and counteract them by offering proper information on blood glucose measurements or the effects of lifestyle changes,’ she pointed out. At the end of the day, she added, no one can be forced to perform SMBG and live a life considering the changes that consequently arise from the SMBG results – the task of Diabetes Nurses is to outline clearly that this might be related to a shorter life.

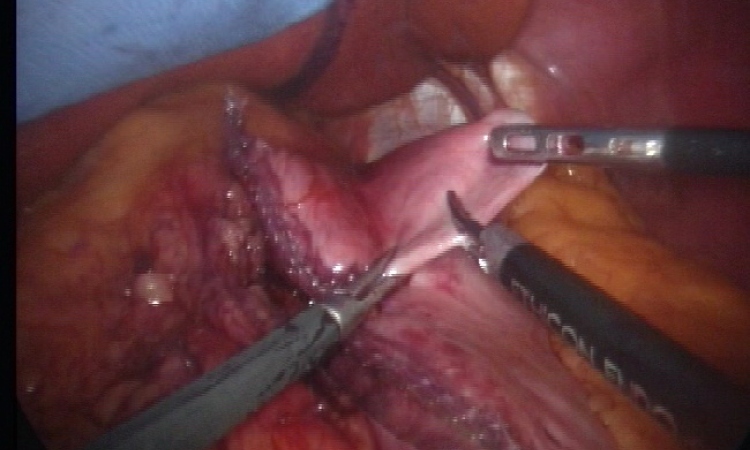

Metabolic surgery

Bypass, gastric band or – the relatively new ‘sleeves’. Surgery can also be an effective weapon in the fight against diabetes.

During the Ethicon Endo-Surgery Johnson & Johnson symposium, Professor Andreas Hamann, senior consultant, medical director and specialist for internal medicine and endocrinology at the Diabetes Clinic Bad Nauheim discussed the Metabolic effects of bariatric surgery with special focus on the outcomes on Type II Diabetes Mellitus. ‘The effect of so called metabolic surgery, that is, the use of surgical means with the objective to improve metabolism, has the largest effect in the case of diabetes.’

Moreover, lipid metabolism and blood pressure – i.e. all components of the metabolic syndrome – are also affected. Not only the weight loss leads to this result, he pointed out. ‘It’s the change in the secretion of various intestinal hormones in particular that is important for diabetes, and specifically the secretion of the incretins. The GLP 1 increases drastically after food stimuli, which affects the glucose metabolism favourably. However, we are still at the very beginning when it comes to researching and explaining these mechanisms, and have some way to go with our research work.’ This is also why there is no satisfactory answer as yet to the question of why diabetes improves only a few days after gastric bypass surgery, whereas the effect of the gastric band depends exclusively on the resulting weight loss, and therefore takes several months.

Generally, a bypass is the most common surgical intervention today and, as proven by numerous studies, is superior to the gastric band in terms of weight loss and metabolic effects. Therefore, in people with a BMI over 45 the gastric band should not be fitted; advice that is often still not followed.

With the gastric sleeve, the situation is different; here about two thirds of the stomach is removed. Latest studies have shown that, in the medium-term, the sleeve has comparable effects on diabetes to those of a bypass. However, as the professor pointed out, this surgery is not reversible, ‘… and as it is a relatively new procedure we also don’t yet have any studies on the long-term effects.’

Which method makes sense for which patient depends on various factors, such as the initial weight, and this must be individually assessed. Metabolic surgery is definitely an effective means to treat diabetes, but it does have risks and side effects. ‘There is a basic risk associated with all surgery. Because of the decreased absorption of food after bypass surgery, essential nutrients, such as vitamins, can no longer be absorbed and must be substituted,’ Prof Hamann pointed out. ‘Both types of intervention therefore require a comprehensive follow-up.’

Many patients are also put off by the high costs of the intervention which, in some countries, is not covered by medical insurers – despite the fact that the costs of treating diabetes can be lowered or even avoided by this type of surgery.

03.11.2010