Diabesity surgery

Morbid obesity is a chronic, lifelong, multifactorial, constitutional disease with negative medical, psychological, physical, social and economic side-effects. Obesity-related secondary diseases are Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension or sleep apnoea.

Report: Holger Zorn

With more than 300 million cases estimated worldwide, the World Health Organisation regards obesity as an epidemic in developed and developing countries. Extreme forms are barely controlled by diet, behaviour therapy or medication. No matter which conservative therapy is chosen, there is a recurrence rate of up to 90%.

In 1991, the American National Institute of Health stated: ‘Gastric restrictive or bypass procedures could be considered for well-informed and motivated patients with acceptable operative risks’ [NIH Consens Statement 1991 Mar 25-27;9(1):1-20]. Naturally, such a statement attracted the attention of the industry: With over 11 million morbidly obese and over 90,000 weight loss surgeries performed annually in Europe, the market potential is very high.

Meanwhile many clinics began surgical programmes – and there is evidence to do that: The 2007 published Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study, a prospective, controlled cohort study with 4,047 patients in 25 surgical departments and 480 primary healthcare centres, includes 2,010 patients who underwent a bariatric surgical procedure and 2,037 patients who were treated conventionally. While the average weight change in the control group was only ± 2%, the patients in the three surgical subgroups -- gastric bypass, vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG) and gastric band -- had an average weight loss of 32%, 25% and 10% after two years and of 25%, 16% and 14% after 10 years [N. Engl J Med 357:741-52].

It should be noted that the VBG or Mason procedure, developed in 1980, is now obsolete while the newer sleeve gastrectomy was not included in that study. Current surgical interventions are, in order of invasiveness, Gastric Balloon, Gastric Band, Gastric Bypass, Biliopancreatic Diversion and Sleeve Gastrectomy.

The gastric balloon

This is made of soft silicone, deflated inserted into the stomach via the mouth and filled with liquid, thus lowering the stomach volume, reducing the amount of food the stomach can hold and causing the patient to feel fuller faster. As the balloon can be left in place for up to six months, this is a temporary procedure and often used as a first step for conditioning the patient for further interventions, e.g. aiming to reduce 10% of weight within six month.

This is useful not only in the bariatric surgery but also for weight loss before a knee or hip replacement. Once removed, the stomach returns to normal. The balloon is also suitable for those patients who won’t tolerate an invasive procedure or who are inoperable because of cardiac insufficiency or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The gastric band

The band is placed laparascopically around the upper section of the stomach. This limits food intake and stimulates the sense of feeling full, resulting in a marked weight loss for the patient.

Johannes Heimbucher, chief surgeon at Maria Hospital Kassel: ‘The gastric band is associated with the lowest short-term risks as well as the fewest side effects long-term.’

The operation gives an expected weight loss of 40% to 50% loss of surplus weight and an improvement in obesity-related secondary disease. Further, it is a reversible technique: if the patient wants, the band may explanted during a minor keyhole surgical intervention. This makes the procedure suitable for a stage concept: if necessary, a more invasive operation can be performed later.

Adjustable bands require that the patient regularly visits an outpatient clinic. If the patient fails to attend the outpatient controls, the practical consequence is that no weight is lost.

The gastric bypass

Developed in 1966 at the University of Iowa, by Edward Mason MD, in this procedure first, a large part of the stomach is cut so that the oesophagus ends in a small mini-stomach and the original stomach volume is reduced. The (large) rest, where the hunger stimulation hormone ghrelin is produced, remains ‘set down’ in the body, and is bypassed without normal function.

The small intestine is then cut at one point and directly connected to the truncated small stomach. The digestive juices will also be diverted and meet the digested food far into the small intestine.

The procedure thus leads the food past most of the stomach and a part of the duodenum, thus considerably reducing fat digestion, food absorption and appetite.

As a result, the patient can then only eat small meals , since the small, new stomach can only hold 20 to 30 ml. Simultaneously the operation presumably reduces the absorption of nutrients.

A gastric bypass leads to a weight loss of approximately 60% to 70% of the overweight and cures or improves secondary diseases. Markus Buechler, head of General, Visceral and Transplant Surgery at Heidelberg University Hospital and President of the German Society for General and Visceral Surgery, actually prefers this procedure. ‘The gastric bypass is technically challenging, but can be performed very safe in experienced hands. The success of this operation is impressive,’ he explains.

The biliopancreatic diversion (BPD)

Developed in 1976 by Nicola Scopinaro in Genoa, this is similar to the gastric bypass procedure but surgically very demanding. The stomach is reduced to a residual volume of 200-250 ml, the small intestine is bypassed and an approximately 50 cm long common digestive tract (common channel) is formed in which food, bile and pancreatic juice are mixed. This leads to a highly effective malabsorption of fat, a rapid and long-lasting excess weight loss of 65-75% with proven results for 25 years – and in 20% of cases to gall stones.

The BPD with duodenal switch is an enhanced procedure, introduced into clinical practice for weight loss surgery in 1988 by Douglas Hess, from Bowling Green, Ohio, using the duodenal switch developed by Tom DeMeester from Los Angeles to treat bile reflux.

Here, the pylorus is preserved, the duodenal stump is closed, the postpyloric duodenum is connected to the ileum, and the built common channel 100 cm long. Thus, the BPD-associated gastric dumping syndrome may avoided -- the rapid gastric emptying that happens when the duodenum expands too quickly due to the presence of sweets or hyperosmolar food from the stomach and leads to nausea, vomiting, sweating, cramping, dizziness or fatigue.

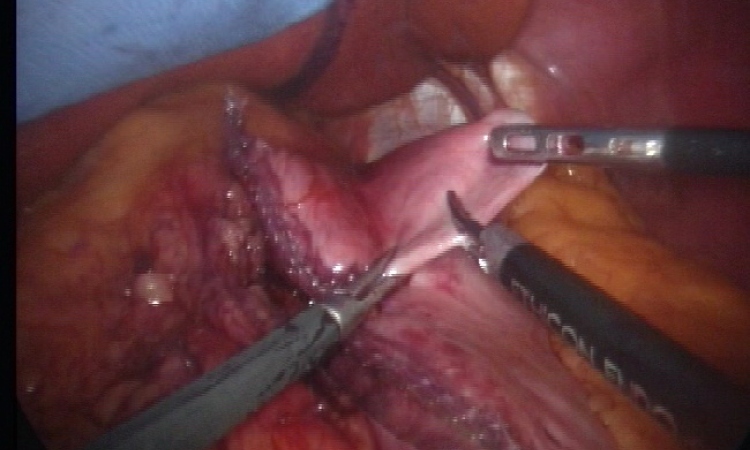

The sleeve gastrectomy

Sleeve gastrectomy for obesity surgery is derived from the very similar Magenstrasse-Mill procedure developed in the 1970 by David Johnston from Leeds and was performed as part of the open duodenal switch procedure 1988 by Doug Hess from Bowling Green, Ohio, and laparascopically as single-stage procedure 1997 by Michel Gagner from Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

Here the biggest part of the stomach is removed. What remains is a two to three inches slim, banana-shaped stomach tube with a volume of 150–200 ml. The stomach is filled faster, the patient feels satiated after small quantities of food. In addition, appetite is reduced because of a drastic decrease of ghrelin from pre-operative 109.6±32.6 fmol/ml down to 35.8±12.3 fmol/ml the first postoperative day (p=0.005), an effect that remains at least six month [Obes Surg (2005) 15:1024-9].

Actually, sleeve gastrectomy is the most increasing bariatric procedure in Germany with about 2,400 procedures in 2010 versus 1,440 in 2009 – a plus of 67%. One reason: sleeve gastrectomy is technically less complex than gastric bypass while the possible excess weight loss is similar to that procedure.

The advantages: There is no anastomosis or new connections made between the stomach and small intestine in this procedure, no rerouting of the intestine, no malabsorption and no dumping syndrome.

Post-surgical lifelong care

A common feature of all surgical procedures is that the patient must take life-long additional vitamins, micronutrients and protein because the organism is put in a deficiency state. For example, iron deficiency may cause anaemia.

Hence, patients must continue to change their lifestyle and food patterns, and life-long aftercare is necessary to maintain the weight loss. Moreover, massive weight loss of ≥15 BMI units results in surplus skin in those regions of the body where the volume of weight loss was greatest. These are typically the stomach, chest, thighs and upper arms, but may also include the face, neck, back and buttocks.

Additionally, there may be residual fat deposits and male mammary gland development that do not go away in association with weight loss. Mostly, plastic surgery is required following weight loss surgery. Indications range from physical difficulties (e.g., skin problems as a consequence of poor skin anchoring) through psychosocial indications (problems in sex life, sport and leisure activities, as well as problems finding clothes that fit over the surplus skin folds) to purely cosmetic indications. Patients often describe themselves as less attractive than before their large loss of weight.

Diabetes surgery on the horizon

Obesity is directly correlated with Type 2 Diabetes mellitus. However, the treatment of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is still a domain of internal medicine.

The therapy consisted of changes in diet, intake of blood sugar-lowering drugs and the injection of insulin. For some time, the above described surgical procedures, bypass and sleeve, have shown that an operation may be an option: The aforementioned SOS study showed that, two years after the bariatric procedure, almost three-quarters of affected patients no longer have diabetes.

In 2009, Henry Buchwald from the University of Minnesota – often called the ‘father of metabolic surgery’ – and his co-workers got the same result in a systematic review and large meta-analysis: The dataset includes 621 studies with 888 treatment arms and 135,246 patients; 103 treatment arms with 3,188 patients reported on resolution of the clinical and laboratory manifestations of Type 2 diabetes.

Nineteen studies with 43 treatment arms and 11,175 patients reported both weight loss and diabetes resolution separately for the 4,070 T2DM patients in these studies. At baseline, the mean age was 40.2 years; body mass index was 47.9 kg/m2; 80% were female, and 10.5% had previous bariatric procedures.

Meta-analysis of weight loss overall was 38.5 kg or 55.9% excess body weight loss. Overall, 78.1% of diabetic patients had complete resolution, and T2DM was improved or resolved in 86.6% of patients. Weight loss and diabetes resolution were greatest for patients undergoing biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch, followed by gastric bypass, and least for banding procedures. Insulin levels declined significantly postoperatively, as did glycohaemoglobin HbA1c and fasting glucose values.

Weight and diabetes parameters showed little difference at less than two years and at two years or more [Am J Med 122(3):248-256.e5]. As in the SOS study, the sleeve gastrectomy was not included in this work.

But in 2008, Vidal and co-workers demonstrated in a randomised controlled study of 91 patients that with sleeve gastrectomy, at least short term, the same anti-diabetic effect can be achieved as with the gastric bypass procedure: At 12 months after surgery, subjects undergoing SG and GBP had lost a similar amount of excessive weight (SG 63.00±2.89% vs. GBP: 66.06±2.34%; p=0.413).

On that evaluation, T2DM had resolved, respectively, in 33 out of 39 (84.6%) and 44 out of 52 (84.6%) subjects after SG and GBP (p=0.618). A shorter DM duration (p<0.05), a DM treatment not including pharmacological agents (p<0.05), and a better glycaemic control (p<0.05), were significantly associated with T2DM resolution in both surgical groups [Source: Obes Surg 18(9):1077-82].

Often the diabetes immediately disappeared after surgery, even though the patients have not yet lost much weight. Rubino and Marescaux from the IRCAD institute in Strasbourg reproduced this observation in an animal study in 29 normal-weight rats with diabetes. After gastric bypass, the diabetes mellitus has been improved, although the animals gained weight after the surgical procedure [Ann Surg (2004) 239:1-11].

Meanwhile, at individual centres, diabetics without severe obesity have been surgically treated and the results are promising. Lee and co-workers from Min-Sheng General Hospital, Taiwan, compared the anti-diabetic effect of a gastric bypass in 201 patients with BMI less than 35 and 619 patients with BMI more than 35 one year after the operation. The treatment goal of T2DM, defined by HbA1C<7.0%, LDL<150 mg/dl and triglyceride<150 mg/dl, was met in 76.5% of BMI < 35 and 92.4% of BMI > 35 patients (p=0.059) [J Gastrointest Surg (2008) 12(5):945-52].

The same author now reports a series of 24 male and 38 female consecutive patients (age 43.1 ± 10.8 years) with T2DM and a BMI of 23-35 who underwent gastric bypass. The mean HbA1c decreased from 9.7 ± 1.9% to 5.8 ± 0.5% in one year and 5.9 ± 0.5% in two years. Complete remission of T2DM was achieved in 57% in one year and 55% in 2 years after surgery [Obes Surg (2011) Apr 17, Epub ahead of print].

De Paula and colleagues from Goiania, Brazil, achieved in 20 diabetic patients with a BMI of 21-34, i.e. with normal weight or class I obesity, two years after surgical intervention even in 90% of cases a good control of T2DM. Bariatric surgery becomes metabolic surgery [Surg Obes Relat Dis (2010) 6(3):296-304].

As a potential mechanism they assume that laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy induced changes on T2DM by mechanisms in part distinct from weight loss, principally involving restoration of insulin sensitivity and improvement of ß-cell function [J Gastrointest Surg (2011) May 10, Epub ahead of print].

All these results lead to a reasonable assumption that bariatric surgery evolves to metabolic surgery. Professor Markus Buechler: ‘Thus, the diabetes is no longer the domain of internal medicine but requires multidisciplinary management. This is especially relevant in light of the frequency of the disease and the associated comorbidities and costs.’

According to the German health report Diabetes 2008 about one in three Germans suffers Diabetes mellitus in the course of his or her lifetime. Presently, around eight million people are diabetic and two million need daily insulin injections.

After the United Kingdom, Germany is the European country with the most diabetics. According to the 2005 published Cost of Diabetes mellitus study, the average annual direct cost per treated diabetic were at €5,262 in 2001, compared with €2,755 for treated the non-diabetic.

In the case of diabetes-related complications, e.g. stroke, kidney failure or severe arteriosclerosis, these costs rise quickly to 20,000 € and more. There are also the additional indirect costs of disability and early retirement in the average amount of €5,019 for diabetics, compared with €3,691 for non-diabetics. Extrapolated to eight million people with diabetes, the annual costs in Germany are € 20 billion.

Therefore, surgery as a therapy option is particularly interesting. A single operation may be cheaper than life-long insulin therapy.

Hence, the first International Diabetes Surgery Summit (DSS), held at the Catholic University of Rome in 2009, called careful interdisciplinary scientific work on this topic: The cut-off of current guidelines -- only patients with severe obesity and an obesity-related condition or morbid obesity are considered candidates for bariatric surgery - was rather arbitrary than supported by scientific evidence.

Gastric electro stimulation to treat obesity and Type 2 diabetes

The gastric stimulator is an almost 20-year-old idea that now becomes a promising interventional approach for the treatment of obesity as well as Type 2 Diabetes mellitus. Actually, there are two CE certified devices in the market: The abiliti system from IntraPace Inc, Mountain View, CA, to treat severe and morbid obesity, and the Diamond system from MetaCure Inc., Kfar Saba, Israel, to treat T2DM with moderate obesity.

The Diamond system

Formerly marketed as Tantalus system, this is a gastric stimulator for inducing comprehensive glycaemic and metabolic control in T2DM. DIAMOND stands for Diabetes Improvement and Metabolic Normalisation Device.

The system consists of an implantable stimulator, a set of electrodes and an external charger. Under general anaesthesia, the electrodes are implanted laparascopically in the stomach muscle.

The system includes a unique and robust eating detection mechanism that, without being inserted into the stomach, senses when the patient eats and induces the non-excitatory stimulation of the stomach causing the stomach to contract stronger. As opposed to gastric pacers the Diamond system only enhances the natural physiological response to a meal at the correct physiological context.

Since 2007, the system is CE approved for treating T2DM. Wolfgang Karl, Managing Director for Germany, about the clinical results: ‘Implanted in over 230 Type 2 diabetics who have exhausted pharmacological options, 90% of the patients benefit by HbA1c or weight reduction, 43% experience a reduction of 1% or over in HbA1c, and 40% reach HbA1c levels of below 7.0%. This is accompanied by a significant reduction in blood pressure, blood lipid profile, and some reduction in weight and waist circumference – with minimal compliance from patients and without the need for an accompanying exercise and diet regime.’

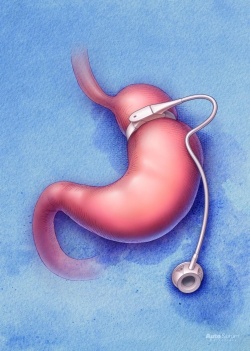

The abiliti gastric stimulator

CE approved for obesity treatment since 2011, this consists of a pacemaker-like implant that is placed on the outside of a patient’s stomach using standard laparoscopic instruments.

The device detects food via sensors placed in the top of the stomach wall and exercise using an integrated accelerator. When the system detects an eating or drinking event, it delivers a series of low-energy electrical impulses to the stomach to create a feeling of fullness, thereby encouraging reduced food intake.

Chuck Brynelsen, CEO of IntraPace, explains: ‘Unlike restrictive procedures, the abiliti system does not impose limits on the type of food a person can consume. Nor does it cause nausea or vomiting should a patient eat too much.’

Information from the food detection sensor provides a detailed picture of food and drink consumption, while the activity sensor tracks exercise and can determine calories burned through various activities.

Using a simple wireless connection, the doctor and patient can view this critical consumption and exercise data, which help support behaviours that lead to sustained weight loss. Further, through an online resource, patients are connected to a valuable support network – a community of individuals helping one another to reach their weight loss goals. Patients in the first clinical study who completed at least 12 months of therapy lost an average of 21% of their excess weight. Based upon an analysis of these data, IntraPace has developed a screening methodology to assist physicians in identifying patients most likely to benefit from the abiliti therapy. Again Brynelsen: ‘When applied to subjects from our first clinical trial, those subjects that would have passed the screening lost an average of 38% of their excess weight, or 18 kg. This tool was employed in the company’s second trial, results that will be presented in August at the IFSO congress suggest it has benefit.’

Thomas Horbach MD, from Municipal Hospital Schwabach, Germany, is among the world’s first to have large experience with both surgical and interventional procedures and explains the rebirth of gastric electrical stimulation: ‘Former products, e.g. the IGS from Transneuronix Inc., were of limited efficacy due to their continuous stimulation. In contrast, the Diamond system stimulates only when a stomach strain stimulus is detected. Thus, a habituation or fatigue effect is avoided.’

This March, Horbach implanted the first CE certified abiliti device after being the principal investigator of the clinical studies leading to a CE certification. His opinion: ‘Not only food and liquid intake is detected by the stomach sensor but also physical activity with the inbuilt accelerometer. This is the first time that I have the chance to guide a patient, to control his compliance. And that's even possible using inbuilt telemetry.’

Thus, new promising tools are available to broaden the surgeon’s arsenal. ‘Each technique has its indication, whether surgically or interventional,’ Horbach says, and cites examples: ‘The pilot of an airline, the self-employed roofer, the taxi driver, daily repeated injections of insulin would mean for all three the end of their professional life. And an irreversible surgical procedure like gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy is not for everyone.’

A comprehensible statement: The latest, as yet unpublished data from the German bariatric surgery registry suggest that staple line insufficiency is up to 7%. By contrast, electrical stimulation is less invasive, less aggressive -- and potentially as effective as surgery without making any changes to the anatomy of the digestive system. However, the long-term result still remains unclear.

No more unclear are the results and value of surgical procedures. Regarding the excessive weight loss, biliopancreatic division seems more effective than sleeve gastrectomy, sleeve more than or similar to gastric bypass, and bypass more than gastric band.

As there is no ideal procedure, new surgical techniques are developed. Recently, Pujol Gebelli from the University Hospital of Bellvitge, Barcelona, presented the laparoscopic gastric plication, a reversible technique derived from sleeve gastrectomy. Because morbid obesity is strongly associated to Type 2 diabetes, about 90% of diabetics may benefit from a surgical procedure, even in cases of moderate obesity. Further, fully T2DM remission seems possible. To describe these facts, the term ‘diabesity’ has been coined.

14.06.2011