Dose reduction for pregnant patients with thromboembolic disease

Suspicion of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in a pregnant patient will quickly bring a radiologist to a choice, where the next step holds potentially significant consequences for both the mother and unborn child.

At ESTI 2012, Fergus Gleeson, MD, from the Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals NHS Trust, will present colleagues a way forward for these cases, which are not frequently encountered in practice, yet represent a leading, preventable cause of maternal mortality.

“It is simply not possible to treat pregnant patients suspected for pulmonary embolic disease in the same manner as those who are not pregnant, and the investigation needs to be approached with care,” he said. “The standard D-dimer test that has a high negative that is a CT with lower but diagnostic image quality, is now obtained with 20 mGy.cm in a standard patient. Converting 20 mGy.cm into effective dose, we reach 0.3 to 0.4 mSv, which predictive value for non-pregnant patients is of no use here, as the levels are elevated in pregnancy,” he said. The physiologic changes in pregnancy mimic pulmonary embolic disease with swollen legs, pelvic pain, and possibly rib pain, he is the upper range of typical doses for chest radiographs. In babies, low-dose cardiac CT can

be obtained with only 2 mGy.cm,” the Belgian radiologist says.

New iterative reconstructions, which are available with the four main CT manufacturers, can be delivered with a reconstruction speed of more than 20 images per second – sufficient for routine CT scanning. Despite the technological progress, the radiologist’s skills are still needed to lower the dose while obtaining an image quality that allows a confident diagnosis. The first important step is to understand how the CT works in terms of dose modulation. The second step, optimisation, requires a certain amount of time.

“As long as you are satisfied with your image explained, making it difficult for a referring physician to make a clinical assessment. Yet concerned they may miss a potentially fatal case of VTE, and with the threshold for suspecting the diagnosis lowered, there is a potential for over-diagnosis.

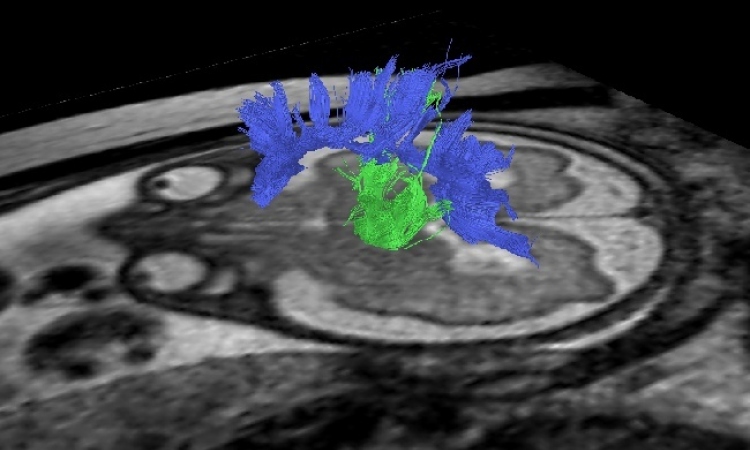

To exclude a chest infection or pneumothorax, the radiologist can proceed with confidence in ordering a chest x-ray. In a second step, compression ultrasonography of the lower limb is required to exclude deep vein thrombosis. “The diagnostic yield for this examination will be low”, Gleeson said, “but it has the advantage that if a clot is found, it points to appropriate treatment without having exposed either the mother or the fetus to any risk of further radiation.” With inconclusive results to this point, the radiologist moves onto uncertain ground in considering a computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA), which is considered the gold standard test for patients who are not pregnant and radionuclide scintigraphy. Both tests expose the mother to a high dose of radiation with a risk of latent carcinogenic effects for radiosensitive breast tissue and uncertain effects for the fetus.

Yet, while it is important to avoid ionizing radiation exposure during pregnancy, the risks of an undiagnosed pulmonary embolism (PE) are much greater than the theoretical risk to the fetus from diagnostic imaging. Gleeson and colleagues at the Oxford Radcliffe NHS Trust in Oxford conducted a number of studies testing different algorithms for patients with suspected pulmonary emboli to determine which produces the highest yield with the lowest radiation dose to both the mother and the baby. First published in Clinical Radiology in 2006, their protocol calls for half-dose perfusion scintigraphy as the first line investigation in pregnant women with suspected PE.

Evidence subsequently published in 2010 in The Lancet found this approach results in “excellent diagnostic accuracy in pregnant patients with a low non-diagnostic rate.” In his presentation at ESTI, Gleeson said he is “going to discuss using the best test in the best order and reducing dose. And I will discuss the limitations of each of the tests, chest x-ray, ventilation perfusion scanning, and CT pulmonary angiography.” “Up to a third of pregnant women risk being exposed to radiation for no measurable benefit if CTPA is used first-line,” he said. Adding that CTPA should be reserved for the small number of pregnant patients with underlying lung disease or a non-diagnostic lung scintigram.

” Where the incidence of non-diagnostic scans with lung scintigraphy is high in nonpregnant patients, mainly as a result of chronic lung disease, “a great advantage we have is that women who are pregnant are young, fit, and often have good cardio-respiratory reserve,” he said. “That really stacks the odds in our favor. It means we can do simple tests that, if normal, will exclude pulmonary emboli.” “All of us in thoracic imaging will come across pulmonary emboli in pregnant women, and it is a difficult topic,” said Gleeson. “This presentation will review the current status of available information, will provide a discussion of the significance of the evidence, and will propose imaging algorithms that are highly useful.”

Profile

Fergus Gleeson was appointed Consultant Radiologist at the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust in 1992 and Professor of Radiology, Oxford University, in 2010. He has written over 150 papers and book chapters on Thoracic Imaging. He was editor of the British Journal of Radiology and is currently on the scientific committee boards of the European Society of Thoracic Imaging, European Congress of Radiology, and the American College of Chest Physicians. He is currently the Director of Imaging for the Oxford NIHR Biomedical Research Centre and the Director of Academic Radiology in Oxford.

25.06.2012