Curse or blessing?

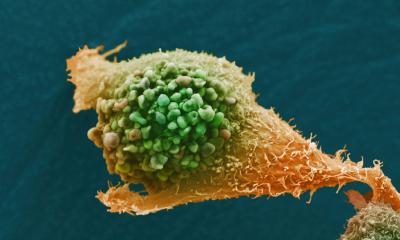

A small prick to sample blood instead of complex pathological or other diagnostic procedures – this is how early cancer diagnosis will be in the near future. Blood tests to diagnose tumorous diseases early are already being researched for clinical use.

However, the results of those tests are not always clear and of benefit for patients. One such negative example is the PSA test to detect prostate cancer, which continues to be controversial due to its frequent false positive and false negative results.

For Professor Roland Repp, Head of the Medical Clinic for Haematology and Medical Oncology at Bruderwald Hospital in Bamberg, blood tests to detect cancer early are of much scientific interest, but their current clinical use is not yet advisable. ‘With the current state of play, I believe it would be highly problematic to use the procedure for therapy control, screening or prediction of therapy response. Should a one-off detection of changes in the blood really be equated with a clinically relevant tumour?’ Prof. Repp asked, during our European Hospital interview.

The professor sees over-diagnosis as a major problem. After all, the body’s own defences may well be able to deal with individual, abnormal cells in the blood but, based on blood test results a patient might end up being labelled as a tumour patient, with all the diagnostic and personal consequences this entails, yet possibly be completely unnecessary. Therefore, this leading oncologist insists that the most valid parameter, i.e. proof of mortality being lowered, must be met before blood tests can be used for screening. There is no doubt that there are indications that abnormal cells can be detected early and that even, in the case of isolated tumours, tumour cells can be found in other parts of the body, and can also circulate in the blood. This appears to have an impact on the patient’s prognosis as well as being useful as an early parameter for therapy response.

Various laboratories are working with procedures that make it possible to detect and purify circulating tumour cells, and even to sequence the entire genome for individual tumour cells. ‘Admittedly, this is fascinating, but we also know it means there are many questions we still have to answer,’ Prof. Repp points out. The most important question is: Does the cell or DNA found in the blood really reflect the driving changes in the tumour cells or is it just a sub-clone or a derivative that is not truly representative of the tumour character?

A positive example

Dr Martin Grimm, an Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon from Tübingen, is much more optimistic about the use of these new tests. He hopes to be able to use the EDIM blood test, trialled in a study for the early detection of prostate, breast and oral cancers, in clinical routine in just a few months’ time. The results of the study, recently published in BMC Cancer, point towards the blood test being utilised as a further diagnostic tool. ‘At the moment, all we can say is that our blood test really does identify cancer patients. In the study, 90% of the tumour patients were correctly, positively identified as such, and the specificity, i.e. the number of non-tumour patients detected, was also around 90%,’ explains the head of the study.

The blood test, which was jointly trialled by Tübingen University Hospital, the German Cancer Research Centre in Heidelberg and the Clemenshospital in Muenster, uses phagocytes that have absorbed enzymes from the tumour and confirms their existence via flow cytometry. According to Dr Grimm, the long-term objective of the procedure is to monitor patients, i.e. more precise therapy control, which manifests as an increase or decrease in recirculating Apo 10 protein and transketolase-like protein 1 (TKTL1). A positive blood test result can also help to facilitate the use of further diagnostic steps. ‘Before scheduling a PET/CT examination at a cost of €1,000 it would be much cheaper to check whether there might be an indication of a tumorous disease with the help of the blood test,’ he points out.

Ultimately, the entire diagnostic and therapeutic procedure will not be impacted, because it will continue to conform to the S3 guidelines for the respective tumour entity. ‘It’s an additional diagnostic tool, and we have shown that it works.’ The procedure has limitations and must not be used for patients with immune suppression, i.e. patients with HIV, or organ transplant recipients. For all other patients the EDIM test is 95% concordant with PET/CT, as shown in a study published in Future Oncology in 2012.

Prof. Repp believes that, in the future, this procedure could compete with PET/CT in terms of sensitivity. However, he points out that, despite many publications, in Germany PET is not yet used to monitor early therapy response of tumours in clinical routine, except i for Hodgkin lymphoma. ‘It’s likely,’ he predicts, ‘that we will have to expect similar delays for the use of blood tests to detect cancer.’

Profile:

Professor Roland Repp is Head of the Medical Clinic V at the Bruderwald Hospital in Bamberg and Extraordinary Professor at the Christian-Albrechts University of Kiel. He also heads the Bamberg Oncology Centre and is speaker for the working groups on ‘Haematologic Neoplasms’ and ‘Clinical Studies’ at the Oberfranken Tumour Centre.

11.03.2014