Chip predicts progression of cancer therapy

So called circulating tumor cells (CTC) seem to be an indicator of the progression and therapy outcome for cancer patients. US- and UK-researchers have shown concurrently that blood tests of CTC's are as reliable as painful biobsies to predict how well patients respond to therapy.

At the ESMO Conference Lugano (ECLU) organized by the European Society for Medical Oncology, researchers showed that changes in the number of circulating tumor cells (CTC) predicted the outcome after chemotherapy in this hard to treat cancer. While investigators from The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in the UK counted the number of tumor cells circulating in the bloodstream of patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer, their colleagues from the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) analyzed cancer cells to determine the genetic signature of lung tumors. Both procedures can accurately predict how well patients are responding to treatment.

CTCs or Circulating Tumor Cells are living solid-tumor cells found at extremely low levels in the bloodstream. "The results add to a growing body of evidence showing that counting these cells is a valuable method for predicting survival and for monitoring treatment benefit in these patients", said Dr. David Olmos from The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in the UK. The british researcher team focused on patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer.

They collected circulating tumor cells from 119 men with castration-resistant prostate cancer at baseline and after 1 and 2 cycles of chemotherapy. Analysing the samples it became clear, that median overall survival was greater than 30 months in patients with less than 5 circulating tumor cells at baseline. A circulating tumor cell count greater than 5 at all time points was significantly associated with shorter overall survival. Change in circulating tumor cell counts at all evaluated post-treatment time points showed that increasing counts predicted worse outcome while decreasing counts predicted better outcome.

Moreover, prediction of overall survival based on circulating tumor cells was "in keeping with prediction based on time-to-progression," Dr. Olmos and colleagues report. "We have observed that patients with declining numbers of circulating tumor cells can see a change in their initial prognosis, reflecting a potential benefit from therapy," he added .

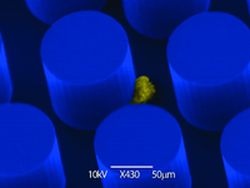

Chip for cancer

The American researcher choosed a more sophisticated way. They demonstrated that a CTC-microchip develop at the MGH, detects and analyzes tumor cells in the bloodstream. Having the genetic signature, physicians can identify those those cells approbiate for target treatment. But the chip is also useful to monitor the genetic changes that occure during the therapy, accordingt to a study that will published on the July 24 New England Journal of Medicine and is receiving early online release.

The researchers around Leica Sequist Sequist of the MGH Cancer Center wanted to find whether the chip could by detecting CTCs helping analyze the genetic mutations in a key protein, the epithilial growth factor receptor (EGFR). It can make a tumor sensitive to treatment with targeted therapy drugs, called tyrosin kinase inhibitors (TKI). Also the response of sensitive tumors to those drugs can be swift and dramatic, eventually many tumors become resistant to the drugs and resume growing

The researchers tested blood samples from patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the leading cause of cancer death in the U.S. The CTC-chip was used to analyze blood samples from 27 patients - 23 who had EGFR mutations and 4 who did not - and CTCs were identified in samples from all patients. Genetic analysis of CTCs from mutation-positive tumors detected those mutations 92 percent of the time. In addition to the primary mutation that leads to initial tumor development and TKI sensitivity, the CTC-chip also detected a secondary mutation associated with treatment resistance in some participants, including those whose tumors originally responded to treatment but later resumed growing.

"Patients found to have resistance mutations before treatment probably won't benefit as much or as long from single-agent TKI therapy as those without such baseline mutations," says Lecia Sequist of the MGH Cancer Center, a co-lead author of the NEJM paper. For those patients oncologist may need to consider other modes of therapy, including combinations of targeting agents or second-generation TKIs that can overcome the most common resistance mutation.

"The CTC-chip opens up a whole new field of studying tumors in real time. If tumor genotypes don't remain static during therapy, it's essential to know exactly what you're treating at the time you are treating it," says Daniel Haber, MD, director of the MGH Cancer Center and author of a pilot study. Something that biobsies taken at the time diagnosis can never tell about changing emerging during a therapy. "When the device is ready for larger clinical trials, it should give us new options for measuring treatment response, defining prognostic and predictive measures, and studying the biology of blood-borne metastasis, which is the primary method by which cancer spreads and becomes lethal."

Picture: Images courtesy Massachusetts General Hospital BioMEMS Resource Center

16.07.2008