Centralising critical care to save funds

Professor Timothy Evans, a leading intensive care specialist believes regionalising critical care into major centres across England and Wales is an ‘inevitable step’ as the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) seeks to make the best use of resources, Mark Nicholls reports.

Along with regionalising critical care into major centres, Timothy Evans, Professor of Intensive Care Medicine at Imperial College London and Medical Director and Consultant in Intensive Care and Thoracic Medicine at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Trust, in London, also maintains such a restructure will offer patients greater access to excellent quality intensive care that will be consistently available 24/7.He will lead the ‘Should we regionalise intensive care?’ debate at the International Symposium of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine (ISICEM) in Brussels (20-23 March).

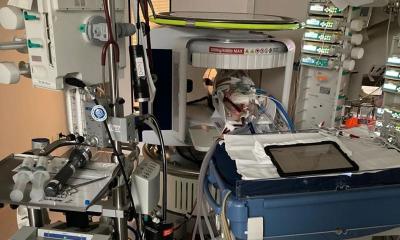

Speaking ahead of the conference, he said, ‘In my view, we do need to regionalise critical care in the same way that there is an increasing focus on regionalising many specialist services; whether that is vascular surgery or cardiothoracic surgery or anything else. As the services that intensive care supports move into regional centres, then the need for advanced critical care support in community or district general hospitals will subside.’ He also pointed out that some of the advanced technologies that are now run by intensive care – such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) - can only be offered in larger units with specific expertise and enough staff to operate them.

An important consideration in moving intensive care from smaller centres into fewer larger centres is the response from the public, who may be dismayed at losing a ‘local’ service. Professor Evans also warned that once intensive care is taken out of a hospital, its future could be in jeopardy. ‘We need to be aware of the consequences – we cannot just say we will regionalise because that has a knock-on effect for all sorts of services. Respiratory physicians might say, for example, that if there is no intensive care, they will not be able continue providing acute respiratory services on a site.’

He said that it was no longer feasible to provide a comprehensive service in every town or city and to receive first class intensive care, patients will have to travel to better-equipped, larger regional centres. ‘The advantage of bigger and better equipped regional centres at this time is that it offers more effective utilisation of resources.’ As said, at these there will be – 24/7 – access to MRI scanners, surgeons, imaging and laboratory services and highly-trained consultants on hand in A&E departments.

However, Professor Evans said that if such changes are introduced, the benefits will have to be clearly communicated to patients. ‘We can’t just say “we’ll close your hospital but you will get something better”, we have to say what it is that’s better and I think that is where the debate needs to come in.’ There are already examples of regionalisation in the UK; children’s services are already centralised and parents are prepared to travel to get a first class service for their child.

‘I regard regionalisation of intensive care as inevitable,’ he added, ‘and if you want excellence in care, that is what is going to have to happen. We are almost saying we need to redefine what constitutes a modern quality service.’ Professor Evans will use data from the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) reports to support his case that change is needed.

He also pointed out that medical leadership in the UK and organisations representing health professionals are starting to acknowledge this pattern of regionalised intensive care will be part of the future of the NHS.

23.02.2012