© AG Reinhardt/UME

News • Good killer cells

Cellular immunotherapy: a new approach against cancer

Aggressive lymphomas – colloquially known as cancers of the lymph nodes – are the fifth most common cause of death from cancer in Germany. Can their treatment be improved via cellular immunotherapy?

This is a possibility Prof. Dr Christian Reinhardt and his team are investigating at the Department of Hematology and Stem Cell Transplantation. In addition, they are developing further interdisciplinary therapeutic concepts and new procedures.

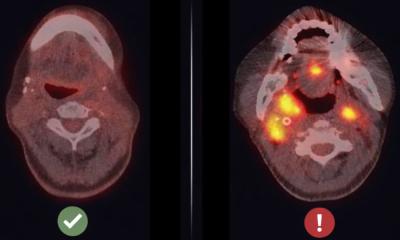

How, in a few words, does this novel immunotherapy work? ‘We’re speaking here about living drugs that dock specifically onto the cancer cells and act against them as killer cells’, answers Christian Reinhardt, professor for internal medicine (hematology). The approach involves extracting T cells (T lymphocytes) from cancer patients, similar to a blood donation, and genetically modifying them on an individual basis: In the lab, they are given a surface molecule that later binds to lymphoma cells in the body, the so-called chimeric antigen receptors (CAR). This enables the genetically modified T cells to kill off the lymphoma cells in the body of the cancer patient.

If we identify the specific drivers of cancers, we can block them. In addition, we are interested in understanding how cancer cells can ward off an attack from the body’s own immune system

Christian Reinhardt

The complex procedure takes two to five weeks, depending on how much time passes between extraction and reinfusion. The method is still quite complex and, at around 300,000 euros per treatment, rather expensive. It is still not always covered by the health insurance schemes, but the positive results speak for themselves, and the processes will be refined further in the coming years. At present, these CAR T cells are used particularly for lymphomas, myelomas, and acute leukemias. ‘Together with the teams from the Department of Internal Medicine (cancer research) and the Department of Dermatology, we conduct clinical trials to analyse whether cellular immunotherapies could later also be used to treat solid tumours, such as lung cancer or melanomas’, reports the expert.

Reinhardt wants to help even more people suffering from cancer – of the lymph nodes, the tonsils, and the spleen, for example. The 46-year-old is therefore in the process of expanding the lymphoma department at the University Hospital Essen (UK Essen) and recruiting even more experts.

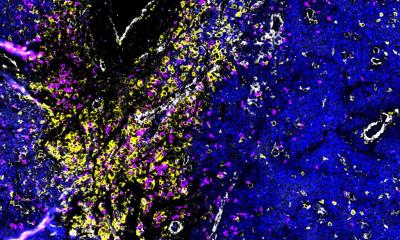

What remains particularly challenging is that tumours continue to develop: they do not stand still in their evolution and are very heterogeneous. It helps to combine experience from the clinic and the laboratory. The team here at the West German Cancer Centre (WTZ) includes numerous dedicated minds: 50 doctors work with the nursing staff on the wards, 15 employees work in the research laboratory, up to 15 work in the diagnostic laboratory, and around ten work in the clinical trials center.

One of the research groups has developed a new mouse model that can be used to understand the processes in human cells even better. ‘It enables us to determine with greater precision which lymphomas respond to which CAR Ts’, says the doctor, describing the steps used to further characterise the chimeric antigen receptor cells. All this helps the researchers to develop individualized therapy approaches and generate preclinical data. ‘Our genetic perspective sets us apart from other hospitals. And even though we have been working on immunotherapy for years, our projects have received new attention since the 2018 Nobel Prize was awarded for the discovery of immune checkpoints.’ Since then, even more extensive research has been conducted on how the patient’s own immune system can be activated to fight against the tumour.

There are also other cancer therapies that can work without chemotherapy. One such therapy that is successful for various chronic and acute leukemias, for example, is certain tablets that do not have a DNA-damaging effect – meaning that they conserve normal tissue – and that intervene by intercepting critical intracellular signaling events in cancer cells. They are extending the chances of survival from months to years already today.

The search for such new chemical substances that can be used to combat life-threatening cancers in a more targeted manner is also the task of a new project. It was launched just a few months ago and is receiving 19.4 million euros in funding from the state government of North Rhine-Westphalia. Under the acronym CANTAR (CANcer TARgeting), scientists are building up a unique network of experts from chemistry, biology, and medicine throughout Germany. The project is being led by the University of Cologne and will run until July 2026. Other participating institutions include the Universities of Duisburg-Essen, Dortmund, Düsseldorf, Aachen, and Bonn, as well as the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Physiology and the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases.

‘If we identify the specific drivers of cancers, we can block them. In addition, we are interested in understanding how cancer cells can ward off an attack from the body’s own immune system’, says Reinhardt, who directs the research on this topic at the Essen project location. Thus, the Department of Hematology and Stem Cell Transplantation and its partner organisations are taking their research in many directions – with the common goal of progressively reducing the use of chemotherapy.

Source: University Duisburg-Essen

30.10.2023