News • Photoacoustic imaging

Breast cancer surgery without lab testing and pathology reports may soon be a reality

Proof-of-concept research investigates whether photoacoustic imaging can be used in place of traditional tissue staining procedures during cancer surgery to determine if all of the tumor has been removed

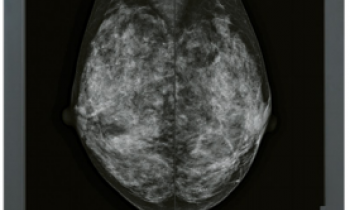

Determining where breast cancer ends and healthy tissue begins is a critical part of breast cancer surgery. Surgeons are used to working closely during surgery with anatomic pathologists who generate pathology reports that specify the surgical or tumor margin, an area of healthy tissue surrounding a tumor that also must be excised to ensure none of the tumor is left behind. This helps prevent the need for follow-up surgeries and involves quick work on the part of medical laboratories.

Thus, any technology that renders such a pathology report unnecessary, though a boon to surgeons and patients, would impact labs and pathology groups. However, such a technology may soon exist for surgeons to use during breast cancer surgery.

Assessing tumor margin with light during surgery

This is proof of concept that we can use photoacoustic imaging on breast tissue and get images that look similar to traditional staining methods without any sort of tissue processing

Deborah Novack

A proof-of-concept study undertaken by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (WUSTL) and California Institute of Technology (Caltech) has been looking at ways photoacoustic and microscopy technologies could enable surgeons to quickly and accurately assess the tumor margin during breast cancer surgeries. The research suggests it could be possible for surgeons to get answers about critical breast tumor margins without employing a clinical laboratory test.

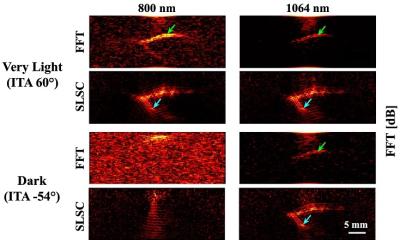

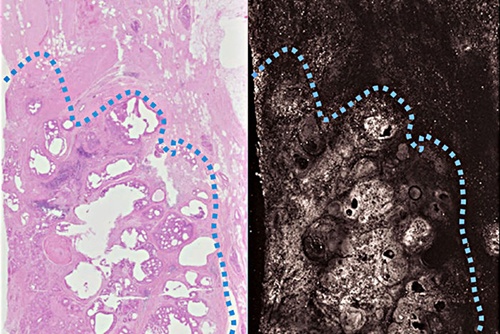

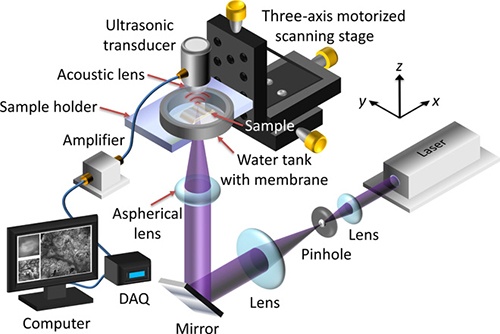

This new technique based on light and sound uses photoacoustic imaging. The researchers scanned a tumor sample and produced images with enough detail to show whether the tumor was completely removed during surgery, a WUSTL news release explained. The researchers scanned slices of tumors secured from three breast cancer patients. They also compared their results to stained specimens.

The photoacoustic images matched the stained samples in key features, according to the WUSTL news release. And the new technology produced answers in less time than standard analysis techniques. But more research is needed before photoacoustic imaging is used during surgeries, researchers noted. “This is proof of concept that we can use photoacoustic imaging on breast tissue and get images that look similar to traditional staining methods without any sort of tissue processing,” Novack added.

Once ready, this technology may well change how surgeons and pathologists collaborate to treat breast cancer patients and those with other chronic diseases that include growths that must be excised from the body.

Current pathology procedures take time, not always useful during cancer surgery

At present, standard breast cancer operation procedures involve surgical and pathology teams working simultaneously while the breast cancer patient is in surgery. Excised tissue is frozen (surrounded by a polyethylene glycol solution), sliced into wafers, stained with a dye, and microscopically analyzed by the pathologist in the clinical laboratory to determine if all cancerous tissue has been removed by the surgeon. “The procedure takes about 10 to 20 minutes. However, freezing of tissue can result in some distortion of cells and some staining artifact. That is why frozen sections are often preliminary—with a final diagnosis based on routine processing of tissue,” according to LabTestsOnline.

Additionally, fatty breast specimens do not make good frozen sections, which requires surgeons to complete procedures uncertain about whether they removed all of the cancer, the researchers noted. “Right now, we don’t have a good method to assess margins during breast cancer surgeries,” stated Rebecca Aft, MD, PhD, Professor of Surgery at WUSTL and co-senior study author.

Up to 60% of breast cancer patients require follow-up surgeries

With three-dimensional photoacoustic microscopy, we could analyze the tumor right in the operating room

Lihong Wang

More than 250,000 people in the US are diagnosed with breast cancer each year, and about 180,000 elect to undergo surgery to remove the cancer and preserve healthy breast tissue, WUSTL reported. However, between 20% to 60% of patients learn later they need more surgery to have additional tissue removed when follow-up lab analyses suggest tumor cells were evident on the surface of a tissue sample, Caltech noted in a news release. “What if we could get rid of the waiting? With three-dimensional photoacoustic microscopy, we could analyze the tumor right in the operating room and know immediately whether more tissue needs to be removed,” noted Lihong Wang, PhD, Professor of Medical Engineering and Electrical Engineering in Caltech’s Division of Engineering and Applied Science. Wang conducted research when he was a Professor of Biomedical Engineering at University of Washington’s School of Engineering and Applied Science. “Currently, no intraoperative tools can microscopically analyze the entire lumpectomy specimen. To address this critical need, we have laid the foundation for the development of a device that could allow accurate intraoperative margin assessment,” the study authors penned in Science Advances.

What is photoacoustic imaging and how does it work?

Photoacoustic imaging’s laser pulses create acoustic waves within tissue, which make way for intraoperative images with enough detail to expose cancerous tissue as compared to healthy tissue.

According to the Caltech news release:

- Photoacoustic imaging (also called photoacoustic microscopy or PAM by the researchers) employs a low energy laser that vibrates a tissue sample;

- Researchers measure ultrasonic waves emitted by the vibrating tissue;

- Photoacoustic microscopy reveals the size of nuclei, which vibrate more intensely than nearby material;

- Larger nuclei and densely packed cells characterize cancer tissue.

“It’s the pattern of cells—their growth pattern, their size, their relationship to one another—that tells us if this is normal tissue or something malignant,” said Deborah Novack, MD, PhD, WUSTL Associate Professor of Medicine, Pathology, and Immunology, and co-senior author on the study.

Whether in surgical suites or emergency departments, technological advancements continue to bring critical information to healthcare providers at the point of care, bypassing traditional medical laboratory procedures that cost more and take longer to return answers. Successful development of this technology would create new clinical collaborations between surgeons and anatomic pathologists while improving patient care.

Source: DarkDaily/Donna Marie Pocius

06.12.2017