100 years of suture technology

We have known since the beginning of Octoberwho will receive the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in Stockholm,this December. Since 1901, according to Alfred Nobel’s legacy,the award has been given to the person(s) who ‘has made the most important discovery in the field of Physiology or Medicine’ – this year Sir John Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka share that great accolade for reprogramming adult cells.A hundred years ago, in 1912, it was French surgeon Alexis Carrel, who received a Nobelfor the development of a procedure for the reconnection of blood vessels and his work on the transplantation of tissue and organs – Carrel paved the way for modern vascular surgery and organ transplantation.

The precipitating event was, as so often, emotional: In 1894 the then French President Marie Francois Sad Carnot diedas the result of an assassination attempt in the Silk City of Lyon – his portal vein had been severed and nobody was able to reconnect it. Carrel, aged 21 years and a licentiate of the University of Lyon, bought the finest needles and learnt the classic techniques of the Canut – the term for the respected local silk workers. He developed the Carrel suture for end-to-end and end-to-side anastomosis of blood vessels and was able to transplant thyroids and kidneys in animals, publishing his results in 1902 (Source: Lyon Med 98:859).

Today, vascular surgery is one of the youngest stand-alone medical disciplines and is characterised by high dynamics. Aortic surgery is one key focus. Aneurysms of the thoracic and abdominal aorta can be treated along with stenosis of the blood vessels supplying the kidneys or carotid artery.

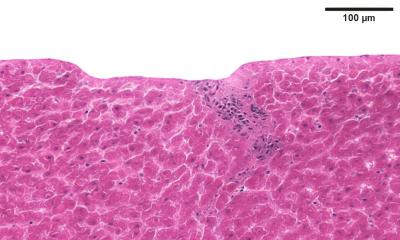

The suture materials of the previous century were not suitable for this. Catgut, for instance, developed in 1868 by the English surgeon and pioneer of antisepsis, Joseph Baron Lister, consisted of strings from sheep guts disinfected in carbolic acid. Although made durable by tanning, these were broken down in the body enzymatically and disintegrated over time.

With the discovery of the textile fibres Polyamide 6 and Polyamide 6.6, better known as Perlon and Nylon, it was only a matter of time until these man-made fibres were also used for surgical sutures. In 1935 Synthofil A, a suture made from polyvinyl alcohol, came on the market, followed in 1939 by Supramid, a perlon suture especially developed for surgery. Not long after, other non-resorbable fibres made from polypropylene and polyester complemented the range. Through copolymerisation of the substances glycolic acid and lactic acid it was finally possible to develop a synthetic material (Vicryl)that is not broken down enzymatically like catgut, but by the body’s own fluids. Plaited and coated, this material is highly tear resistant and facilitates the use of finer sutures.

For other hollow organsanastomosis can only be created through sutures techniques with great difficulty, and often not at all – the leak rate would be just too high. Here, started in 1908 by the Hungarian Humer Hültl, the staple suture technique was developed (see EH 2/2011 p. 4-5), which is actually what really made diabetic surgery possible (see EH 3/2011 p. 5-7).

A large part of suture materials is not used for the connection of tissues or organs but for wound closure. However, staples, clips or glue arefrequently used in place of sutures. The market is large and with an average annual growth rate of 2.2% also relatively stable. In 2007, analysts at Medmarket Diligence LLC, the Californian market research company for medical products, forecast a market volume of US$ 281 million for sutures, US$151 million for stables, US$80 million for clips and US$93 million for glues for the most important European markets in Germany, UK, Italy, France, Spain and Benelux (Source: Medmarket Diligence, LLC, Report #S180, ‘Worldwide Surgical Sealance, Glues, Wound closure and Anti-Adhesion Markets 2008-2015’, published: Oct 2010). France was listed in this analysis with US$ 42 million for suture materials – a multiple of the money awarded to Alexis Carrel a hundred years ago.

A little lesson in suture material

Surgical sutures can be resorbable, absorbable or non-resorbable. They are made from biological or synthetic material. Biological material can be of animal (sheep gut) or botanical origin (cotton, silk). Synthetic sutures consist either of synthetic material (polyamides, polyester, polypropylene) or steel (stainless steel). Surgical suture material is divided into monofilament, polyfilament (plaited, twisted, twined), pseudo-monofilament (sheathed individual fibres) and coated (gummed individual fibres).

02.11.2012