Article • Contrast enhancement

Sonic boom with bubbles

Illuminating blood vessels, opening the blood-brain barrier and delivering drugs. What will be the next big thing that tiny microbubbles can do?

Report: John Brosky

In the beginning there was the bubble, even if no one was quite sure what they were supposed to do with it. Once injected into the blood stream, it was clear to anyone conducting an ultrasound examination that these microbubbles introduced by Bracco Imaging under the name SonoVue (sulphur hexafluoride microbubbles) absolutely and instantly highlighted blood vessels.

Twenty years later, microbubbles are popping up everywhere as clinicians continually demonstrate new and innovative applications, not only for detecting and diagnosing disease, but more recently for treating it as well. Tiny microbubbles in the blood have already revolutionised medical imaging, yet hold a promise for going much further.

In September 2016 Bracco brought together in Geneva scientists and clinicians from globally renown research centres for the 9th Global R&D symposium entitled Bubble World to explore the numerous opportunities for microbubbles, not only to see-and-treat disease in the human body, but to explore and discuss future potentials for medical and non-medical applications.

Diagnostic Imaging

There is a long list of things where microbubbles have proven to add value to clinical practice, according to Professor Peter Burns, Chairman of Medical Biophysics at the University of Toronto.

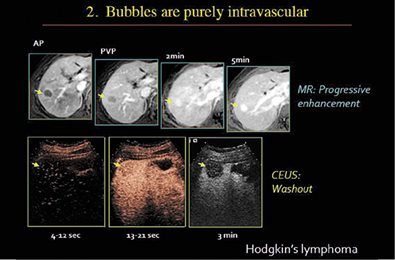

One of the first, the most successful, and most widely used application of microbubbles is for the identification and differentiation of cancer from other vascular entities. Cancerous tumours are known to create their own blood vessels, but no one had ever seen so quickly and clearly these micro networks until microbubbles illuminated them on the ultrasound screen. SonoVue highlights where there is blood flow and where blood is not flowing but should be, Burns explained. Ischemia imaging with ultrasound in combination with bubbles can answer clinical questions such as whether myocardial function has been successfully restored after an intervention.

A closely related area is imaging inflammation to identify malignancy, he said, as an emerging practice and an alternative to the current standard of care. Following conventional practice, he said, ‘Younger people being diagnosed with this condition will receive 20 abdominal CT exams by the time they are 20 years old. 'Bubbles are the only true intravascular contrast agent in diagnostic medicine and magnificent amplifiers of ultrasound with a sensitivity that is capable of identifying individual bubbles,’ Burns said in his presentation.

Therapeutic applications of micro bubbles

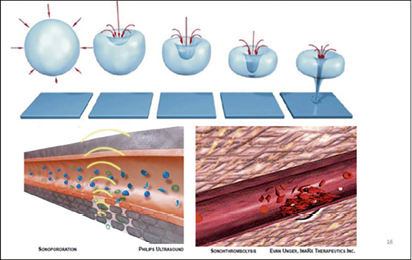

In November 2015 Professor Kullervo Hynynen was part of a scientific team that achieved a world-first in human medicine by using microbubbles to open temporarily the blood-brain barrier. The technique opens a new approach for delivering drugs to fight brain cancer, as well as creating a novel approach to treating neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

The Chair of the Image-Guided Therapy group at the University of Toronto, Hynynen worked with colleagues at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre to apply focused ultrasound beams at a point where microbubbles were circulating. The vibration of millions of bubbles under the sonic signal caused the tight network of interlocking cells to loosen enough for a limited flow to pass out of the blood vessel and into brain tissue. Today, only 2% of drugs for treating a brain tumour actually reach the tumour because they are blocked by the blood-brain barrier. Opening this barrier with microbubbles allows a significantly greater dose of chemotherapy to penetrate to tumour tissue. ‘This also presents the possibility to deliver novel drugs, such as DNA-loaded nanoparticles, viral vectors, or antibodies to the brain to treat a range of neurological conditions,’ he told colleagues in Geneva.

Piercing this barrier also allows the body’s own natural defence mechanisms to fight disease. Hynynen said researchers found, in animal studies, a partial restoration of memory after brief blood-brain barrier opening, which they believe is the result of two effects. First, the body’s own agents of the immune system were able to attack and reduce the amyloid plaque that is characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease, and second, the treatment stimulated growth of neurons.

Jessica Foley, the Chief Scientific Officer at the Focused Ultrasound Foundation in Charlottesville, Virginia told scientists at the symposium that the high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) platform for one company has already received regulatory approval to treat the brain and that many other companies are now seeking approval. ‘There are more than 35 companies advancing HIFU technology, an exponential growth after many years of this being a research tool,’ she said, adding that 100,000 patients have been safely treated using HIFU to destroy tumours.

‘Breaching the blood-brain barrier opens up a new frontier to non-invasively deliver therapies for a number of brain disorders,’ she said. ‘Microbubbles loaded with a therapeutic and activated with focused ultrasound have the potential to penetrate the blood-brain barrier and treat tumours. There are powerful synergies here.’

The future of ultrasound imaging

This is a true revolution and we are only at the beginning.

Prof. Michel Tanter

It can take 20 years from the discovery of such headline-making achievements until they come into routine clinical practice, cautioned Professor Michel Tanter from the advanced engineering College of Physics and Chemistry in Paris, France. He then launched into a presentation of yet another break-through potential for microbubbles in super resolution ultrasound medical imaging.

Building on work that won a Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 2014, his group has demonstrated the first ultrasound-based microscopic imaging technique that allows clinicians to non-invasively look deep inside living tissue for the early detection of cancer tumours or cardiovascular and neurologic pathologies.

‘This is a true revolution and we are only at the beginning,’ Tanter said. ‘Yet we can be sure the technique will become more powerful with even faster image processing capabilities emerging and smaller, enhanced microbubbles.’

Bubbles outside the body

Microbubbles are popping up in multiple fields outside medicine as scientists apply them to solving problems as diverse as cleaning tools, and even endodontic treatment, to smoothing the powerful churning of turbines to produce electricity.

Professor Michel Versluis is from the Physical and Medical Acoustics Physics of Fluids Group at the University of Twente, in the Netherlands, which is part of a consortium of two other universities that recently won funding of €36 million from the Dutch government to advance their work.

Using ultra-fast optical imaging of microbubbles, his group hopes to increase the efficiency of catalytic reactions to optimise processes for various energy and materials sources, such as fossil fuels, biomass and solar energy. Mohamed Farhat, Senior Scientist at the Polytechnic University in Lausanne, Switzerland is investigating the potential of microbubbles to fix problems caused by cavitation in hydraulic machines. ‘Bubbles produced in industrial flow processes cause nothing but problems for noise and vibration, due to cavitation. ‘Turbines crack, plants are shut down and the costs of these effects are very high. What we are asking is how we can turn these bad bubbles into good bubbles?’ he said.

New horizon

Dr Peter Frinking, Senior Scientist at Bracco Research in Geneva, agreed that it took 20 years for the current generation of microbubbles to reach the point where today they are advancing science as well as enhancing diagnostics and patient therapies.

‘What will be the next big thing? What does all this mean for the next generation of microbubbles?’ he asked the scientists.

‘We need a greater understanding of the acoustics, the biology and the potential applications, which is what this symposium has been all about. We may not be able to predict the future, but we certainly want to be ready for it,’ Frinking concluded.

06.11.2016