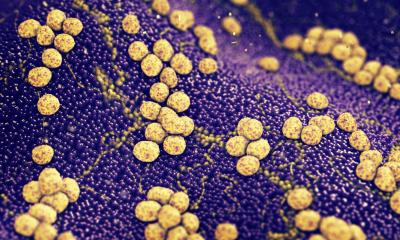

MRSA

Breast cancer drug eats superbug

Researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences have found that the breast cancer drug tamoxifen gives white blood cells a boost, better enabling them to respond to, ensnare and kill bacteria in laboratory experiments. Tamoxifen treatment in mice also enhances clearance of the antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogen MRSA and reduces mortality.

“The threat of multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens is growing, yet the pipeline of new antibiotics is drying up. We need to open the medicine cabinet and take a closer look at the potential infection-fighting properties of other drugs that we already know are safe for patients,” said senior author Victor Nizet, MD, professor of pediatrics and pharmacy. “Through this approach, we discovered that tamoxifen has pharmacological properties that could aid the immune system in cases where a patient is immunocompromised or where traditional antibiotics have otherwise failed.”

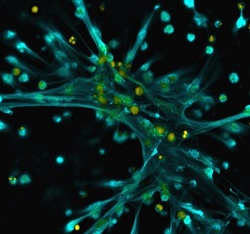

Tamoxifen targets the estrogen receptor, making it particularly effective against breast cancers that display the molecule abundantly. But some evidence suggests that tamoxifen has other cellular effects that contribute to its effectiveness, too. For example, tamoxifen influences the way cells produce fatty molecules, known as sphingolipids, independent of the estrogen receptor. Sphingolipids, and especially one in particular, ceramide, play a role in regulating the activities of white blood cells known as neutrophils.

“Tamoxifen’s effect on ceramides led us to wonder if, when it is administered in patients, the drug would also affect neutrophil behavior,” said first author Ross Corriden, PhD, project scientist in the UC San Diego School of Medicine Department of Pharmacology.

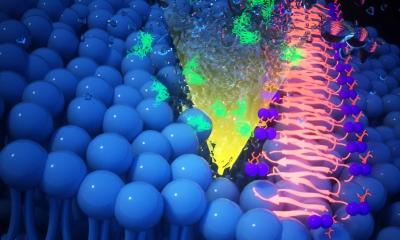

To test their theory, the researchers incubated human neutrophils with tamoxifen. Compared to untreated neutrophils, they found that tamoxifen-treated neutrophils were better at moving toward and phagocytosing, or engulfing, bacteria. Tamoxifen-treated neutrophils also produced approximately three-fold more neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), a mesh of DNA, antimicrobial peptides, enzymes and other proteins that neutrophils spew out to ensnare and kill pathogens. Treating neutrophils with other molecules that target the estrogen receptor had no effect, suggesting that tamoxifen enhances NET production in a way unrelated to the estrogen receptor. Further studies linked the tamoxifen effect to its ability to influence neutrophil ceramide levels.

The team also tested Tamoxifen’s immune-boosting effect in a mouse model. One hour after treatment with tamoxifen or a control, the researchers infected mice with MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), a “superbug” of great concern to human health. They treated the mice again with tamoxifen or the control one and eight hours after infection and monitored them for five days.

Tamoxifen significantly protected mice — none of the control mice survived longer than one day after infection, while about 35 percent of the tamoxifen-treated mice survived five days. Approximately five times fewer MRSA were collected from the peritoneal fluid of the tamoxifen-treated mice, as compared to control mice.

There are two caveats, the researchers said. First, while tamoxifen was effective against MRSA in this study, the outcome may vary with other pathogens. That’s because several bacterial species have evolved methods for evading NET capture. Second, in the absence of infection, too many NETs could be harmful. Some studies have linked excessive NET production to inflammatory disease, such as vasculitis and bronchial asthma.

“While known for its efficacy against breast cancer cells, many other cell types are also exposed to tamoxifen. The ‘off-target effects’ we identified in this study could have critical clinical implications given the large number of patients who take tamoxifen, often every day for years,” Nizet said.

Source: University of California, San Diego Health Sciences

22.10.2015