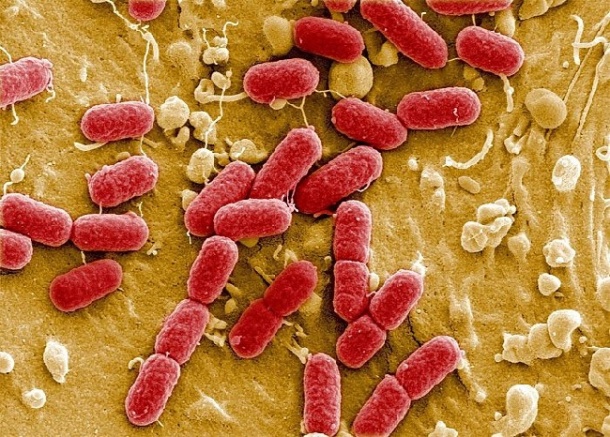

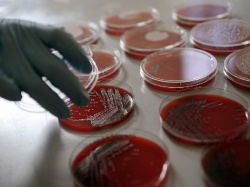

Well organised against EHEC

In late May, a particularly aggressive and new strain of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) posed an enormous challenge for northern German hospitals. In Hamburg, the focus of the epidemic, more than 1,000 people fell ill, about 180 of them seriously, after getting into contact with the bacterium.

Report: Meike Lerner

Many of the precise consequences of the pathologies were unknown. 150 patients who suffered complications were referred to the University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE). It was a challenge for both clinicians and management. Within hours several isolation units with highly specialized staff had to be set up, the number of dialysis systems had to be increased significantly and 400 units of plasma concentrate had to be available every day. Professor Jörg F. Debatin, Medical Director and CEO of UKE, told Meike Lerner (European Hospital) how the University Hospital Hamburg managed this gigantic task with the help of its well established interdisciplinary cooperation, fast and efficient structures and non-bureaucratic support from other institutions.

When faced with a sudden crisis such as the recent E. coli outbreak in Germany, Prof. Jörg F. Debatin explained that coordinated action and interdisciplinary cooperation are initially vital. ‘We were lucky, so to speak, since these management approaches are well established at UKE, so we could respond immediately to the EHEC outbreak and set up a crisis management team,’ he explained. ‘This team consisted of about 20 people from different areas – obviously clinicians, mainly nephrologists and gastroenterologists, later on also neurologists, but also key staff from nursing care management, logistics and hygiene, microbiologists, the blood bank and medical technology. Moreover, the interdisciplinary intensive care team and the interdisciplinary emergency team played a crucial role in the process.’

Another important issue, he pointed out, is flexibility. ‘Our new hospital, with its modular design, turned out to be a major advantage because it provided us with sufficient room to manoeuvre. But, above all, it was the flexibility of our staff that was really impressive – they were prepared to work across departments and even professional lines.

‘Reorganising the tasks and schedules of 8,500 employees is quite a management task, but it can only be done successfully if everybody moves in the same direction and if everybody pulls his or her weight. It worked out great. As a matter of course the cardiologists, for example, helped out in the internal medicine department because the internists were more than busy with the acute care of the EHEC patients.

‘Another advantage was the fact that all our ICU beds are centrally managed. This allowed us to set priorities quickly and to establish two HUS (haemolytic uremic syndrome) units with 12 beds each, without having to neglect the other 1,300 ICU patients.

‘In addition, the electronic patient record proved invaluable. The fact that all patient data are available in digital format and accessible from anywhere in the hospital significantly facilitated both interdisciplinary cooperation and bed management. We always knew exactly the status of resources and patients, which helped us to identify and manage reserves. Even on the busiest wards, the situation was always under control. The electronic patient record was also an advantage in terms of real-time documentation.

‘Administration of the antibody Eculizumab has to be documented tightly and exactly. During the peak of the crisis two nursing team members were relieved of their usual tasks and took care of all documentation requirements. It went smoothly -- without the EPR I’m sure this would have been a major nightmare.

When did you realise that, despite those positive basic conditions, the hospital was reaching its limits?

‘In the beginning we considered two factors to be crucial: paediatric dialysis and plasmapheresis for adult patients. While paediatric dialysis turned out to be fairly easy to handle, plasmapheresis was one of the biggest challenges throughout the crisis.

‘Every day, 60 patients required a plasmapheresis, which meant that we had to immediately increase our capacities tenfold. We managed by recruiting UKE staff who were familiar with plasmapheresis no matter what their actual field of work was. We had cardio technicians, cardio surgeons, nurses from the anaesthesia department and people from the blood bank help out. We also received fast and non-bureaucratic support from external institutions, such as the Association for Home Dialysis, office-based physicians and other hospitals.

‘In this critical initial phase, we transferred ten percent of the patients who suffered from less severe haemolytic uremic syndrome to hospitals in Hannover and Berlin. When we started to administer Eculizumab towards the end of the first week after the outbreak we were able to reduce the plasmapheresis procedures, which freed up some resources.

EHEC became a Germany-wide problem. How did coordination and communication work nationally?

‘Kudos to the German medical community! Within twelve hours, the German Society for Nephrology managed to agree on a nationwide review protocol for Eculizumab. This means that the patients can be sure to be treated according to the same high standards, no matter which hospital they are in. Praise also for the cooperation of all hospitals and healthcare institutions. They all went out of their way to help – some even sent staff to support us, for example from the University Hospital Heidelberg, the Armed Forces Hospital and the Association for Home Dialysis. Not to forget the industry: companies responded immediately and made additional dialysis equipment available.

As a university hospital UKE is also involved in EHEC research. In this sudden crisis, what were its tasks and how did it coordinate that work with other university hospitals?

‘From a scientific point of view it was important to design methods very quickly for the collection and reporting of data. We focused on issues surrounding data collection and archiving, and drafting questionnaires. This is crucial for the follow-up and is the domain of epidemiologists and statisticians in our Clinical Trial Centre.

‘As far as coordination with other institutions is concerned the exchange of knowledge has top priority. All scientists at UKE who were involved in this crisis are eager to analyse the data quickly and comprehensively. We thus hope to be able to present initial scientific insights from UKE physicians on this endemic shortly. ’

16.06.2011