Total artificial hearts and ventricular assist devices today

Artificial hearts, originally designed to bridge the time on the waiting list for a heart transplant, in recent years have increasingly become an independent treatment option for patients with chronic heart failure (HF).

Discussing this trend with Professor Roland Hetzer, heart surgeon and chairman of the DeutschesHerzzentrum Berlin (DHZB, German Heart Institute Berlin), he explained that the DHZB, a specialist centre for heart treatment, has the most comprehensive programme worldwide for the implantation of artificial hearts. In the past 23 years over 1,670 of these devices have been implanted in HF patients.

‘The original concept of artificial heart developers was to create a total artificial heart (TAH) for permanent replacement of the natural heart,’ he said. ‘Clinically, TAHs were used for the first time in 1969 in Houston and then again in Salt Lake City in 1982, but the complications associated with TAHs were so heavy that the American government stopped their long-term use. Since that time TAHs, where the natural heart is removed, were only used to bridge the time to heart transplantation, in a so-called bridge-to-transplant therapy. As a kind of side-product of the TAH development, mechanical circulatory support systems for a heart left in place had been developed. These systems, generally called ventricular assist devices (VADs), assist either the left or right ventricle, or both at once. Because VADs were, after all, more suitable for a bridge-to-transplant therapy, they then almost replaced TAHs. Both systems, the TAH and the VAD, can only replace the pumping function of a failing heart. Regulatory and hormonal functions have not been taken into account up to now.’

If TAHs failed to permanently replace a heart, could VADs be an option to permanently replace the natural heart?

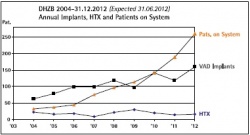

‘Heart transplantation is, beyond controversy, still the best therapy for chronic heart failure. I personally oversee patients living for 28 or 29 years with an implanted natural heart. However, mainly due to organ scarcity, a heart transplant is an option only for a highly select group of patients, to a degree that I call it a casuistic therapy. In addition to this, significant improvements have been made in VAD technology. Therefore, we have increasingly used VADs for permanent therapy in recent years. I’ll give you some data: At the beginning of the 1990s, we still performed 120 heart transplants at the DHZB per year; in 2011 only 34 and this year just 13, so far. By contrast, implantation of VADs has increased: In recent years we had around 170 and for 2012 we anticipate 200 implants – and I think this trend will continue.

‘Why? I think the rate of heart failure will increase because the more successful we are in treating acute heart disease, such as acute infarct or acute myocarditis, the more of these patients will eventually, after further years, develop chronic heart failure. In the demographic curve you see that, in the patient group beyond 70-75 years of age, chronic heart failure is by far the most prominent heart disease, but we only perform heart transplantations up to the age of 65-70 years due to increasing complication rates beyond this age. Therefore the only way to treat this patient group even nowadays is to implant a VAD.’

Is VAD implantation difficult?

‘The surgical procedure is not very demanding and I think it is so standardised that every cardiac surgeon can perform it. Particularly for older patients it’s a good therapy because they don’t have a great trauma and are immediately better. The oldest patient in whom we have successfully implanted a VAD is 83 years old.’

How does a VAD work?

‘Nowadays, practically all such assist devices follow the rotational principle, working like a fast-running turbine with a rotor producing continuous blood flow. These small turbines are becoming smaller and smaller at present weighing about 90 to 130 grams. This year we are expecting pumps that are not larger than my thumb. The pumps are implanted into the body and only the energy source is located outside, connected by a cable running through the skin. For the patient, the energy support is relatively easy to manage and he or she can wear it in a bag on the body, which means mobility is possible.’

Isn’t the continuous blood flow unhealthy?

‘As I implanted the first rotational pump in humans in 1998, of course I was quite curious whether something unusual would happen because of this non-physiological blood flow, but we did not see any immediate sequel. Now, after a while, we can see that some things may develop, for instance aortic valve incompetence, some coagulation disorders, or the formation of some abnormal small vessels in the bowel that might bleed. Of course, since we only have experience over about eight years, we don’t know what this type of circulation might cause in humans after 20 years. It has been speculated that arteriosclerosis or hypertension might be accelerated, but this is not proven.’

How long can patients live with a VAD?

‘Patients who have had such rotational pumps the longest have had them for nine years. We estimate that the current generation of VADs technically may last around 15 years and, of course, they can be exchanged if there is technical wear. In addition the devices are being continuously improved to increase their durability. There is an energy transmission concept, for example, using plugs that are screwed to the skull to avoid infections or cable breaks. Then there’s the possibility of transferring energy via induction through the intact skin. So, I think in the coming years the implantation of assist devices will probably be one of the most frequent therapy modalities we will have.’

PROFILE

With over 40 years’ experience, Professor Roland Hetzer ranks among the most experienced cardiac transplant surgeons worldwide. He studied medicine in Mainz and Munich universities and then surgery at the Hannover Medical School, and was a clinical fellow in cardiovascular surgery at the Pacific Medical Centre in San Francisco and Stanford University.

Back in Germany as a senior physician at the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery at Hannover Medical School, he qualified as a professor and established his research in heart transplantation.

He became a professor at the Free University Berlin In 1985 and subsequently established the DHZB, German Heart Institute Berlin, of which he is chairman and medical director of cardiac surgery.

Prof. Hetzer performed Germany’s first successful TAH implant, the Bücherl total artificial heart, as a bridge to transplantation, in 1987. Then, in 1998, he implanted the first VAD with a rotational pump worldwide. Named after its inventor, Michael DeBakey MD, the event heralded the worldwide success story of rotational pumps.

Additionally a professor at the Humboldt University of Berlin, he is also medical director of the Heart Centre in Cottbus.

02.11.2012