Article • Digital pathology

Today’s tissue for tomorrow’s research

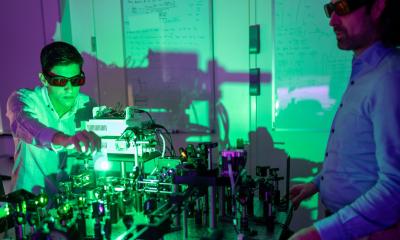

Specialist biorepositories are helping advance personalised medicine by supporting the availability of human tissue for research using digital pathology techniques. The pivotal role of the Glasgow Tissue Research Facility (GTRF) in making tissue available to shape new therapies and treatments was outlined in a presentation to the online “Transforming Digital Pathology – Integrating AI to Move towards Precision Pathology” event.

GTRF Head of Research Dr Jennifer Hay explained how the unit utilises “digital pathology to enable high quality and high quantity research.”

The GTRF, set up in 2019 and based at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, works with the NHS, pathologists, researchers and industry, to provide a high-quality research service for precision medicine. It works closely with the NHSGGC Biorepository, which is an operational unit of the NHS Research Scotland hub responsible for the governance associated with the collection, storage and use of human tissues to make it available for medical research and clinical trials as well as ensuring that legal and ethical requirements are met.

In her presentation, “Today’s tissue for tomorrow’s research”, Dr Hay said: “NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde Biorepository is a unique service within the NHS and provides a wide range of human tissue and biomolecular material for the medical research community. The GTRF links in with the Biorepository to provide a unique service for researchers in digital pathology.”

Recommended article

Article • Digital pathology

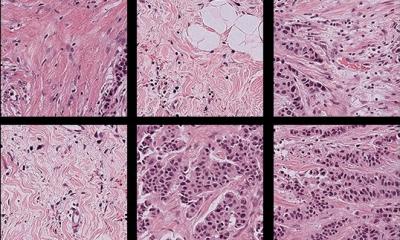

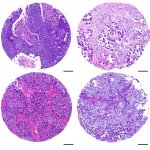

An exciting new era for tissue microarrays

A new generation of tissue microarrays are delivering more efficient and time-effective solutions to answering complex clinical and scientific questions. Sitting at the core of this new approach is digital pathology, allowing specific and targeted analysis of small areas of tissue.

Applications for access to tissue are made directly to the biorepository, scrutinised by an expert panel for ethical and scientific merit, and released to researchers for approved studies. She continued: “GTRF bridges the gap between the NHS, University of Glasgow and industry for tissue-based research. It supports the process from tissue acquisition through to analysis to provide first-class digital pathology, TMA construction, image analysis, and histology services.”

With tissue-based research underpinning the development of precision medicine, which is changing the approach to disease, diagnosis and treatments, GTRF has an increasingly important role to play. “Histopathology-based techniques have vastly improved in the last five years and, with increasing demands for high-quality research projects, services for tissue-based research are expected to grow to meet these requirements,” added Dr Hay.

Researchers need to be “tech savvy” and “IT literate”

Tissue images from breast, bladder, colorectal cancer, prostate, renal and other organs and parts of the body, are stored on a GTRF server accessible via a website log-in, enabling approved researchers to view, download, share or annotate images. The tissue microarrays (TMAs) contain some 250 patients on one side with linked data.

There is a different language between IT and scientists but we need to start talking in the same way. It is a steep learning curve to understand the language of IT but it is necessary

Jennifer Hay

GTRF has supported a range of research projects, including major colorectal cancer studies on imaging and deep learning, new therapies, and assessing whether tumour-budding in colorectal cancer is ready to be applied in clinical practice. The centre also has a role is utilising Big Data to improve patient diagnosis and prognosis, with stored images used to develop software tools that enable automatic delineation of tumour areas. In addition, it has been a partner in the INCISE (INtegrated TeChnologies for Improved Polyp SurveillancE) study, which aims to transform bowel screening in the UK by developing a tool that can predict which patients with precancerous growths in their bowels will develop further polyps.

However, Dr Hay said several challenges remain in digital pathology research in areas such as governance involving ethics, documentation, data sharing agreements and anonymisation when using human tissue. She also emphasised the need for researchers to be “tech savvy” and IT literate. “There is a different language between IT and scientists but we need to start talking in the same way,” she said. “It is a steep learning curve to understand the language of IT but it is necessary.”

As for the future of digital pathology research, she said data storage was a consideration, while grant funding needs to factor in IT support and storage costs. She also pointed to a benefit of digital pathology being minimal tissue usage. “Tissue is vitally important for patients and pathologists but now we can ‘cut once and have multiple analysis’ from on piece of tissue as there is a huge data output which can be mined for years to come,” she said.

Other topics discussed at the event organised by DigiBase included looking at where the biggest bumps in the road to full digital pathology are; progress in clinical pathology digital implementation; AI in cellular pathology; AI and digital diagnostics for global health applications; accelerating acute diagnosis; and computational problems in computational pathology. (MN)

Profile:

Dr Jennifer Hay is Head of Research at the Glasgow Tissue Research Institute and a qualified Biomedical Scientist. Her role includes project managing TransSCOT which is the translational arm of the SCOT trial, an “international, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial” involving adult patients with high-risk stage II or stage III colorectal cancer. She is also a work package lead for the INCISE research project.

20.05.2021