Head and Neck Radiology

The Radiologist’s Fear of Spaces

Imaging the head and neck is only rarely practised in radiology training and is highly complex and particulate, which is why, during our discussion with Professor Birgit Ertl-Wagner, Head of MRI at the Institute for Clinical Radiology at Grosshadern Hospital, Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, she pointed out that many radiologists are not comfortable with orientation around this area. When outlining the difficulties for us, the professor even created a kind of Google map of very significant areas in head and neck radiology.

Report: Sascha Keutel

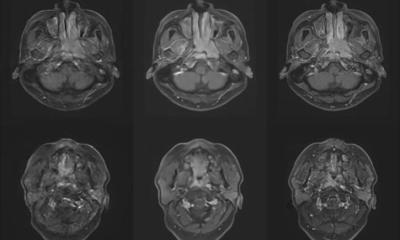

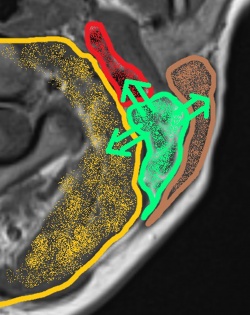

‘Radiology and surgery of the head and neck divides different parts of the neck into different “spaces”,' she explained. ‘These are separate areas of different size and different content in the neck that have a topographical connection and are usually surrounded by fascia components. Another reason why the neck, and particularly the subject of head and neck imaging, scares some radiologists is that this is the part of the human body with the narrowest cross-sectional area. All structures situated in this part of the body are positioned in the smallest space, and indeed a lot of important structures can be found here, from top to bottom and vice versa: the entire supply of the brain – arterial and venous blood, the spinal cord, spine and, additionally, the complex postural muscles which facilitate the flexibility of neck movement. Respiration and nutrition obviously also run through the neck.

‘To cap it all off, everything in this area runs simultaneously and with a low cross-section: there is little space and volume for so many processes. To tackle this situation the structures are grouped into different compartments or spaces, similar to the floor plan of a building. The walls of these spaces within the neck correspond with the fascial planes that mark the borders between the individual spaces.

‘It’s rather complicated. Many radiologists, and particularly those not specialised in head and neck imaging, find it difficult to locate these spaces because they are not situated at right angles, like those on a floor plan, but rather nested and interlaced. The fascia structures can only be identified with enough experience.

‘At first glance, the entire area looks like a terribly confusing map. Therefore, it’s all the more important to attribute any masses/pathologies to the correct spaces because mistakes may result in a wrong diagnosis.

‘The differential diagnoses vary depending on which space you are looking at. It is important to be aware of the pathology, because tumours have different ways of spreading. In some spaces a tumour, or infection, may spread intracranially, in others they won’t. Others in turn have connections with the mediastinum through something that is appropriately known as “danger-space” and constitutes a type of “connecting door” into the mediastinum that makes it possible for tumours or infections to spread in a mediastinal direction. If you are not aware of these paths these processes can be overlooked and/or wrongly assessed.’

PROFILE:

Prof. Dr. Birgit Ertl-Wagner is Head of Magnetic Resonance Imaging at the Institute for Clinical Radiology, Klinikum Grosshadern, Munich, since 2009. In November 2012 she was awarded the W2-Professorship for Clinical and Experimental MRI at the University of Munich. Along with structural, MRI-based diagnosis her specialties include cerebral flow-, perfusion- and pressure quantification with MRI, diffusion tensor imaging and functional MRI techniques. She trained as a radiologist and neuroradiologist. She spent several periods as a researcher in the US, most recently as William R. Eyler Fellow of the RSNA in 2012. In 2013 Ertl-Wagner was presented with the Therese von Bayern Award and the Felix Wachsmann Award of the German Society of Radiology.

21.04.2015