Population Imaging

Ethical considerations arise from incidental findings

ECR 2015 evoked Shakespeare´s repertoire as delegates were asked to ponder the ethical implications of incidental findings in large population imaging studies in Vienna.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

”The central ethical problem of incidental findings in MRI research is whether or not these findings should be disclosed,” stated Reinold Schmuecker, professor at the Institute for Philosophy, Centre for Advanced Study in Bioethics, University of Muenster, Germany, as he closed the session on large multicentre studies. “It is similar to the central question in Shakespeare´s Hamlet - to disclose or not to disclose: that is the question.”

Incidental findings put the researcher in a situation that requires a decision between two ethical demands. In order to understand this conflict, one must remember the difference between population based imaging studies and clinical trials, he explained. An epidemiologic study investigates the health of an individual recruited from the general population and not a set of patients. The primary aim of epidemiologic research is to obtain quantitative data on diseases in the general population. Population based studies are not interventional studies, meaning their aim is to evaluate the health status of the research subject without intervening.

Ethical problems arise for instance when a whole body MRI evaluation in an epidemiologic study reveals a kidney tumor that is still treatable if immediate measures are taken. “If we follow the moral principle that most people will probably agree on, i.e. do not harm anyone and help to the best of your ability, it is obvious that a finding of this type, which is highly relevant for the subject´s quality of life and life expectancy, must immediately be disclosed,” the expert pointed out.

In the case an incidentally detected abnormality is life threatening, there is not only a general moral obligation to provide assistance but also a legal one in most countries. However, according to Schmuecker, there is a contrary moral duty and it would suggest non-disclosure, because disclosing incidental findings compromises the integrity of the study. “Disclosure provides study subjects with information about their health that is not available to the general population of which they are supposed to be representative. With this knowledge they can seek treatment earlier than they would have without the study. The disclosure of incidental findings thus leads to a biased sample, compromising the methodological validity of the study and generating knowledge that cannot be generalized to the overall population,” he said.

A classic example of biased sample is the so-called Literary Digest disaster. In 1936 the American journal Literary Digest conducted a telephone survey among 2.3 million readers in the run up to the elections between Alf Landon and Franklin Roosevelt, and very inaccurately predicted a landslide victory for the Republican candidate Landon. The journal had surveyed a huge sample but did so by telephone; Back then people who had the telephone were people of high means, who tend to vote Republican - therefore the method choice was a mistake. “This poll nicely illustrates the problem we are discussing here: when systematic sample error occurs while a study is underway, this cannot simply been remedied by increasing the sample size,” Schmuecker said.

Ethical dilemma in epidemiologic studies goes far beyond methodological issues. The results of these studies are intended to help improve preventive care for future generations; hence there is a genuine ethical conflict between the well-being of individual research participants currently living with undetected disease(s) and the well-being of future patients who might potentially benefit from the research. “In light of these considerations, the question is how we should balance the well-being of research subjects against that of future generations. In other words, are we justified to compromise the well-being of our study subjects in the name of science? Ethically, the question arises even if in the consent procedure a research subject explicitly states that he or she wishes not to be informed about incidental findings,” he said.

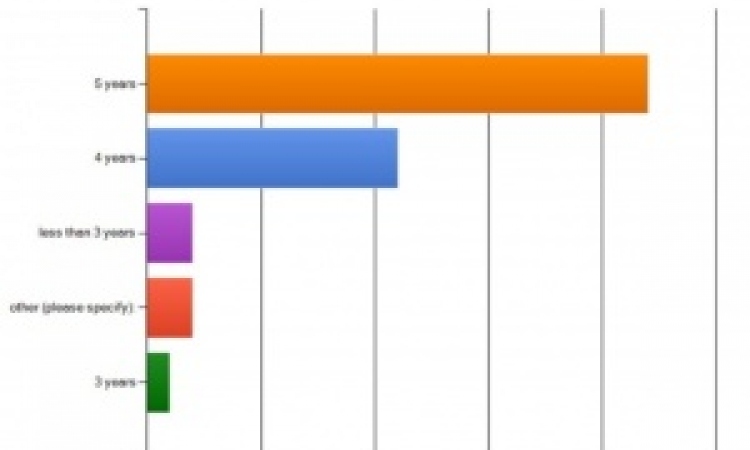

In the following panel discussion, speakers highlighted the numerous situations in which clinical findings are not clear enough to begin with. “There is a grey area between findings that are very evident, do harm and can be treated, and the ones that are harmless. But the majority of findings are in between,” said professor Fabian Bamberg from Tuebingen University Hospital in Germany, who presented the German Cohort study earlier in the session.

Myriam Hunink, a professor of radiology and clinical epidemiology at Erasmus University, the Netherlands, and adjunct professor of health decision science at Harvard University, who attended the session, asked whether a decision analysis model could be a feasible approach in this scenario. “You would need to make some samples to decide if decision analysis would be ok. We just don´t know what the imaging findings really mean and the best we can do is follow up patients until we have some outcome from the data. We have to wait until we have at least some findings and then maybe implement some of those models,” Bamberg offered.

Steffen Petersen, a professor at the London Chest Hospital at Queen Mary University in the UK, who presented the UK Biobank study, explained how intervening in epidemiological studies could potentially harm the patient. “When we do look at images and find potential harmful findings, there´s also a potential to expose the patient to radiation. You do tests, you do biopsies, there may be an infection and there may be complications. So I think that´s something we do not really quite know yet. The ideal scenario would be you do not even look at the images, they go in the box, and participants consent to that. Then you have one certainty that the patient or participant is not harmed because they do not know any more or less than they did before coming into the study. When revealing and starting to look at the images, you don´t know whether you are helping the individual and there is a huge amount of potential to harm. I´m actually much more convinced that we´re harming by disclosing rather than by not disclosing, but then again data is missing,” he concluded.

Further speakers were ESR President Gabriel Krestin, professor Norbert Hosten and associate professor Sönke Langner, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University Greifswald.

06.03.2015