Article • Wound infection

The importance of suture material

Wound infections after surgery are not uncommon and can be fatal. In Germany, postoperative wound infections are now the most common type of hospital acquired infection (HAI), with a proportion of 24%.

Report: Bettina Döbereiner

An expert on infection prevention and control, Professor Axel Kramer, who directs the Institute for Hygiene and Environmental Medicine at the University of Greifswald, Germany, believes that suture material may be an underestimated aspect of prevention. Postoperative wound infections are typical complications that occur after surgery. They typically develop through entry of pathogens, mostly bacteria, via the skin or mucous membranes into the surgical site.

According to the Hospital Infection Surveillance System KISS, 1.6 out of 100 surgical interventions in German hospitals lead to surgical site infections; this results in some 267,000 postoperative wound infections annually (2014 figure). These are only estimates – precise data is lacking. However, the fact is that some of these nosocomial infections could be prevented – between 20-60% of them, Kramer estimates. In terms of the total number of postoperative wound infections annually this would represent between 53,000 – 160,000 fewer cases.

How best to prevent SSIs is one of Kramer’s specialist research areas. At the 4th Forum on Infection Prevention and Control held by the German Medical Technology Association (BVMed), in Berlin last December, he explained his recommendations for the best options of prevention.

His urgently recommended strategies to tackle SSIs include eradication of existing infections before elective surgery, standardised pre-operative skin antiseptics, sterile covering of the surgical area, no shaving (if required then clipping instead of shaving), aseptic, tissue-conserving working methods, sterile clothing, surgical hand disinfection, intact surgical gloves (if necessary double gloving), surgical masks and perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis (PAP) and – to complement all this – the respective suture material.

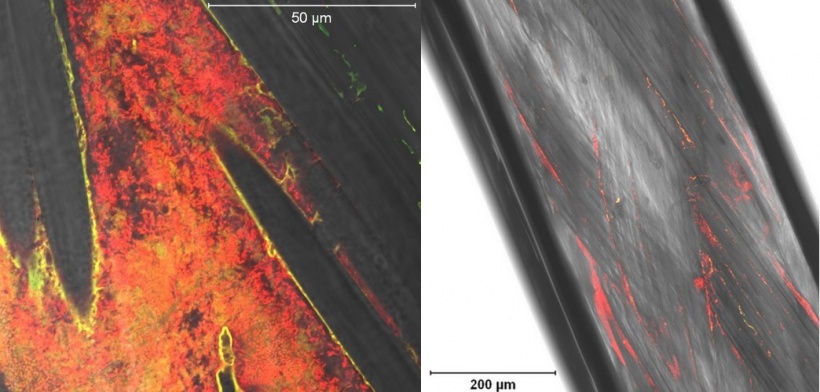

Underestimated implants

The surface of a conventional, sterile suture (braided vicryl) with a length of 150cm has, Kramer calculated, the same surface area as the side of a CD cover. ‘This means that, during the formation of a biofilm, around 325 billion pathogens can colonise this area and, in the case of multi-layer biofilms even up to a trillion pathogens,’ he explained. ‘The suture material is in fact an implant, but unfortunately often not recognised as such,’ Kramer points out.

This implant bears the same risks as other implants. The number of pathogens required to cause infection is far lower around the suture material. Therefore, the probability of infection via the suture material, particularly in body areas with high bacterial colonisation, such as the colon with its complex intestinal flora, is markedly high. It is also possible, Kramer says, that a biological film may form around the suture and thus protect the pathogens from immune defence. The suture can almost act like a ‘slide’ into deeper layers of tissue and cause infection there.

Triclosan coated sutures

Kramer therefore recommends the use of antiseptic-impregnated suture material, particularly for visceral surgery. The number of SSIs here is significantly higher than the average 1.6, at 9.36 per 100 surgical interventions. However, even if all measures of prevention are adhered to, invasion of pathogens, such as from the intestine, can never be completely prevented even with antimicrobial suture material, Kramer emphasised.

Currently, the only antimicrobial suture material available is coated with the antimicrobial substance Triclosan. Impregnation with Triclosan prevents the biofilm development on the suture material. However, there is a gap in effectiveness against the fourth most common cause of SSI, P. aeruginosa. However, irrespective of this, the benefits of antimicrobial suture material continue to be controversial.

For abdominal surgery, four meta analyses now confirm a reduction in the SSI rate through the use of Triclosan-coated sutures. However, a PROUD study showed no significant impact on superficial (A1) or deep (A2) surgical site infection after elective, median abdominal laparotomy. However, says Kramer, after consolidating the data from the PROUD study with data from four further studies it was possible to document clear superiority of the antiseptic suture material (Diener et al 2014). Potentially positive results have so far also been achieved in breast cancer surgery and heart surgery.

For Kramer the trend, at least for abdominal surgery, is obvious, even though more proof is still required. He is convinced by the benefits. The University Hospital Greifswald has therefore been using antibacterial suture material since 2005.

Self-control with checklist reduces SSI rate

Irrespective of the research situation it is obvious that only a combination of a whole bundle of measures will lead to success in the prevention of wound infections. Kramer therefore suggests specific bundles of measures to combat SSIs, which each surgical department should establish, train its staff in and then monitor. At the Centre for Colon Cancer, in Greifswald, this has been successfully implemented since 2009. Surgeons control adherence to all-important measures of prevention via a checklist prior to commencing surgery. This has led to a stable reduction of superficial (A1) and deep (A2) SSIs by an average of 60% in the period between 2011 and 2015, Kramer says.

Conclusion: If postoperative wound infection was to be reduced by more than half through suitable measures of prevention, such as seen in this example from Greifswald, based on the aforementioned prevalence rate in Germany, this would save around €1.8 billion – and, most importantly, it would spare many patients the unpleasant and sometimes even deadly effects of wound infections.

Profile:

Professor Axel Kramer MD is a specialist in Hygiene and Environmental Medicine and former head of the Institute for Hygiene and Environmental Medicine at the Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University Greifswald, Germany. In this role he combines teaching with research, as well as the management of infection prevention- and control for the University Hospital Greifswald. He is a member of the commission for ‘Hospital Infection Prevention- and Control at the Robert Koch Institute’ and a founder member of the German Society for Hospital Hygiene (DGKH), having been its president from 1990 to 2010.

25.07.2016