Article • MR Fingerprinting and Compressed Sensing

The impact of a radiological transformation

MR Fingerprinting and Compressed Sensing are two procedures that will facilitate much faster MR sequencing than currently possible – and more. ‘MR Fingerprinting will revolutionise MRI scanning,’ according to Dr Siegfried Trattnig, head of the Centre of Excellence for High-Field MRI at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria. ‘It will completely change the way MRI scans are currently being carried out.’

Report: Michael Krassnitzer

Image courtesy of Prof. Trattnig, Medical University of Vienna, Austria

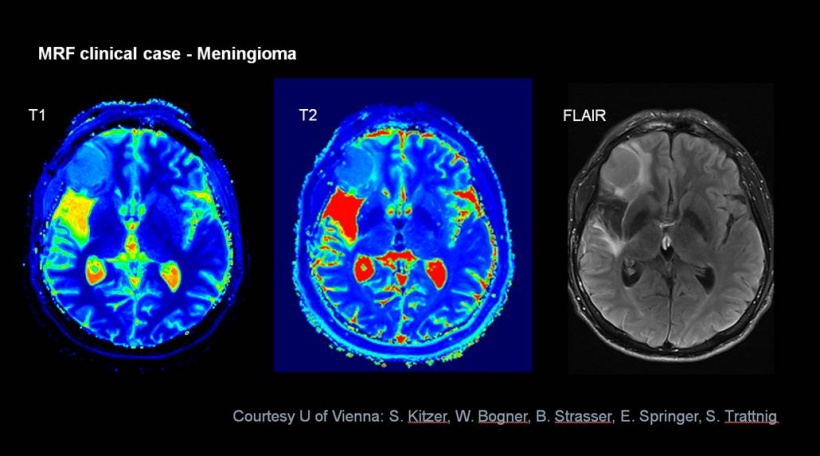

MR Fingerprinting (MRF) will make it possible to produce very individual quantitative maps of a patient’s tissue, so-called T1 and T2 maps (the longitudinal relaxation time T1 and the transverse relaxation time T2, together with the proton density, are the basic parameters of MRI). They virtually create an MRI fingerprint of a patient, as Trattnig explains: ‘The maps created with MRF are not dependent on the sequence or the scanner. No matter whether a patient is examined in Vienna, Heidelberg, or New York: MRF always delivers the same results. This is therefore the first ever chance to standardise MRI and to use it advantageously in multicentre studies.’

One stop shopping

MRF also opens up other opportunities: ‘T1 and T2 maps can be used to produce the conventional contrast images that radiologists are familiar with, arbitrarily,’ Trattnig confirms. This speeds up processes significantly. Trattnig refers to it as ‘one stop shopping’. ‘An individual sequence, which lasts about five minutes, produces all quantitative data – T1, T2, proton density – and additionally we are able to produce all the contrast images from this data hitherto produced with the previous conventional imaging procedure.’

Image courtesy of Prof. Trattnig, Medical University of Vienna, Austria

The principle behind this is not that easy to explain. ‘MRF is a fundamentally new approach for carrying out MRI scans,’ Trattnig explains. So far, MR images were built on the T1 or T2 relaxation curves with fixed sequence parameters (such as TR time or flip angle). However, MRF has no fixed parameters. ‘A single spiral sequence acquires a large number of images, with the parameters for each individual one of these images varying at random,’ the radiologist explains. Within 30 to 40 seconds, 3,000 to 5,000 images with different TR times and flip angles are being created. On their own, these images are of low quality as only individual points of a k-space are reconstructed.

However, if one of these points (pixels) is tracked on all images, one obtains a meaningful signal intensity curve over time for this pixel. This signal intensity curve represents the MRI ‘fingerprint’ for the patient. It is then compared with a database (dictionary). This database can calculate the Bloch equations using the randomly selected sequence parameters and the expected T1 and T2 relaxation times of the tissue examined.

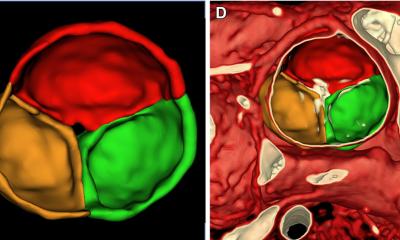

Using a pattern recognition tool, the best match of the patient’s MR Fingerprint (the individual signal intensity curve) with the database is established and this best match shows the patient’s precise T1 and T2 distribution, as well as proton density distribution within the tissue based on T1 and T2 maps. Cardiac imaging is one of the possible clinical applications. T1 mapping is becoming increasingly important for dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or myocarditis. ‘T1 mapping without MRF however is time-consuming, with a sequence taking up to 8-10 minutes,’ explains Trattnig: ‘With MRF, we can create T1 and T2 maps with a single breath hold and then produce contrast images synthetically using the data.’

Image courtesy of Prof. Trattnig, Medical University of Vienna, Austria

Compressed Sensing

Compressed sensing also accelerates MRI – but in a different way. The general public is aware of data compression from mp3 or JPG files. JPG typically facilitates the reduction of a file size to a fraction of a compressed image. This means that a large proportion of the acquired data is irrelevant to accurately display the image.

An MRI scan usually takes so long because a large number of points is read from the MRI raw data matrix (k-space) to produce images. ‘Many points in the k-space are actually irrelevant for the specific examination,’ Trattnig explains. The best example for compressed sensing is MRI angiography, for which only the blood vessels are relevant but not the surrounding tissue. According to an overview study, compressed sensing can speed up MRI angiography by factor 12.5.

Areas of application

The patient can breathe normally whilst k-space data is continuously being acquired and then retrospectively reconstructed

Siegfried Trattnig

Whilst MR Fingerprinting is still at an experimental stage, compressed sensing is already being trialled in clinical routine. A new 3-Tesla scanner from Siemens is already offering compressed sensing for examinations of the abdomen and liver. ‘The patient can breathe normally whilst k-space data is continuously being acquired and then retrospectively reconstructed,’ Trattnig explains. It can also be used favourably in cardiac imaging for patients with arrhythmia or limited lung function. Previously, radiologists had to choose between high temporal or high spatial resolution: ‘For the first time ever, with compressed sensing, both is possible simultaneously,’ Trattnig points out. This facilitates better detection of tumours and improved differential diagnosis.

Trattnig believes that compressed sensing can also be used in paediatric radiology. At the moment, carrying out MRI scans for small children involves sedation or an anaesthetic; this can later have a negative impact on neurocognitive abilities during development. With the fast sequences made possible through compressed sensing, an MRI angiography, for instance, can be carried out much faster for small children, helping to reduce the time required for sedation or general anaesthetic considerably.

Profile:

Dr Siegfried Trattnig is a Professor for Radiology focusing on High-Field MRI at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria, where he has also been medical director of the High-Field MRI Research Scanner since 2000 and medical director of the High Field MRI Centre (HFMRC) since its foundation in 2003. The professor is also a member of more than 50 committees in all important international radiological, orthopaedic and MRI associations and has authored more than 480 specialist articles.

10.07.2018