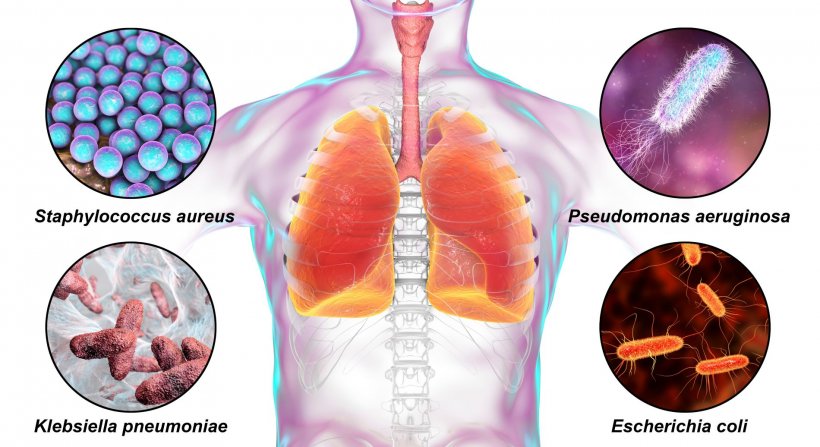

Image source: Shutterstock/Kateryna Kon

Article • Where are the infectiologists?

‘The hygiene plan is nothing but a fig leaf’

Nosocomial infections cause more deaths than traffic accidents – a stunning discovery made in a recent German study. Worse: infectious diseases long thought eradicated in Europe, such as measles, tuberculosis (TB) and, more recently, syphilis, are also implicated.

Report: Anja Behringer

The increasing number of patients places an additional financial burden on healthcare. But – and this might be the good news – hospital hygiene finally receives top priority in German hospitals. Hygiene campaigns began ten years ago and today sanitiser dispensers are ubiquitous throughout any hospital. Alas, to little avail. No significant improvement can be reported despite the fact that a slew of new professions and specialisations have been created: physician hygiene specialist, nurse hygiene specialist, hygiene risk assessor, or infectiologist. We appear to be losing the battle against hospital-acquired infections (HAIs). The problem is exacerbated by an ageing population, more susceptible to diseases, and by antibiotics losing their efficacy.

What can be done? Hygiene was the dominant topic, dissected from back to front during the European Health Congress, held in Munich. Results were not particularly encouraging – passing the buck appeared to be the chosen approach.

Hand hygiene – the be-all and end-all in the battle against microorganisms

The quantifiable – and increased – use of sanitisers does not allow any conclusions as to the quality of the handwashing procedure

Johanna Knüppel

‘Wash your hands after going to the loo and before meals’ – generations of children have learned this advice, and it’s as valid today as 50 years ago; according to the World Health Organisation, 60% of all infectious diseases are transmitted by hand contact.

For Johanna Knüppel, expert and speaker of the German Nurses Association (Deutscher Berufsverband für Pflegeberufe – DBfK) in Berlin, the root cause of the long known and still unsolved problem is the glaring lack of staff, time and space. She does concede that the handwashing campaign did sharpen awareness, but, she asks, how do we disinfect? ‘The quantifiable – and increased – use of sanitisers does not allow any conclusions as to the quality of the handwashing procedure. According to manufacturer information, the substance should be applied for 30 seconds. If nurses were to follow these instructions, they would spend 2.5 hours per day sanitising their hands.’ No wonder, people try to cut sanitising corners – and increasingly, hospital managers understand the problem. Even the clinical bigwigs display ‘organised neglect’, as Professor Walter Popp, Vice President of the German Society of Hospital Hygiene (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Krankenhaushygiene) and Medical Director at Hykomed GmbH, in Dortmund, Germany, noted when he observed his colleagues in the operating room. It’s not even hand sanitising that worries Popp but ‘the way they handle patients with ears not covered’. A detail that goes unnoticed – and which is a symptom of the problem. The infection protection guidelines issued by the German Commission for Hospital Hygiene and Infection Prevention (Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention – KRINKO) are increasingly vague, as Popp underlines. Moreover, he adds, nobody knows from where all the needed hygiene specialists are supposed to come; and, even if they did exist, they alone could not level off the heap of problems.

In 2015, a 10-point plan to push back HAIs and antibiotic resistance, published by the then German Federal Ministry of Health, was met with enthusiasm. One of the few clearly phrased items in the plan: a special program designed to recruit additional hygiene staff by the end of 2016. When, after a transition period, the hygiene recommendations became binding, the target date was moved – to the end of 2019. Recruitment turned out to be sluggish. The Federal Ministry of Health put the blame squarely on the hospitals and regional governments. What the ministry failed to see: candidates are not rejected by the hospitals; candidates simply do not exist. After all, working conditions in hospitals are not particularly attractive.

Recommended article

Article • Microbiology & hygiene

HAIs are one problem – MDROs another

In view of the increase of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO), the WHO has declared antibiotic resistance one of the biggest threats to global health. MDROs have become a major problem particularly in hospitals. Professor Dr Georg Häcker from the Institute for Microbiology and Hygiene at the University Hospital Freiburg, explains some strategies to prevent hospital-acquired infections (HAIs).

Hygiene is rising to a top priority

Whilst physicians are the worst of role models, nurses are busy trying to implement instructions that are not grounded in any reality – a reality in which patients who have not yet been screened for microbes are parked in a hallway until rooms become available and where cleaning service contracts are put out to tender each year and the cheapest providers usually are awarded the contract without employees’ competence being checked. The good news: physicians, at least in Germany, tend to be more reluctant to prescribe antibiotics. In Germany, 25 percent of all patients receive antibiotics, in southern European countries the rate is twice that number – 55 percent in Greece, for example, Popp points out. With increasing migration, infection control has become an international issue. While MRSA is retreating, the non-resistant variant of this bacterium causes thousands of deaths each year, according to a German Society for Infectiology report. In Germany, there are 400,000 to 600,000 treatment-associated infections each year, 10-15,000 of which are fatal. They are connected with hospital and non-hospital care as the Federal Ministry of Health has explained on its website since 2015. However, one third of these infections could be prevented with hygiene protocols, including measures such as appropriate equipment sterilisation.

Well-meant programmes from ABS to APS

ABS doesn’t work, since the freshly certified ABS experts, once they do exist in a hospital, don’t have time for education and recommendations

Walter Popp

‘Since the “Microbial Threat” conference, held in Copenhagen in 1998, the 2001 EU report on “Prudent Use of Antimicrobial Agents in Human Medicine”, so-called Antibiotic Stewardship Programmes (ABS) are considered necessary to rein in antibiotic resistance by rational anti-infection protocols. ABS programmes have proved to influence resistance, costs and use positively, and have become an important component of patient safety in modern healthcare,’ the ABS Initiative’s website states.

Popp begs to differ. In his opinion, first there is no sufficient data pool on the administration of antibiotics in hospitals. Secondly, he claims, ‘ABS doesn’t work, since the freshly certified ABS experts, once they do exist in a hospital, don’t have time for education and recommendations.’ Johanna Knüppel agrees. ‘The main task of hygiene experts in nursing is handling the hygiene plan – which is nothing but a fig leaf anyway.’

The Aktionsbündnis Patientensicherheit e.V. (APS), an initiative founded in 2005 to focus on patient safety, is optimistic, since its first international day of patient safety was held with WHO support: ‘APS will continue to point out the issues that obstruct safe patient care.’

To make a long story short: Improvements, or even solutions to the hygiene problem, are not in sight even though everyone is busy working on them. And politics? In the political arena, cynics would say, the motto ‘only a dead patient is a good patient’ appears to prevail. The ones still alive need to try to be well informed and prepare themselves for their hospital stay, for example when surgery is scheduled. The best way to begin: Ask your family doctor to screen you for multi-resistant bacteria, try to eradicate them and make your immune system fit for the hospital environment. If you do this, you enter the OR as a ‘healthy’ person, and your chance of leaving the OR and hospital in the same healthy state increases considerably.

18.11.2019