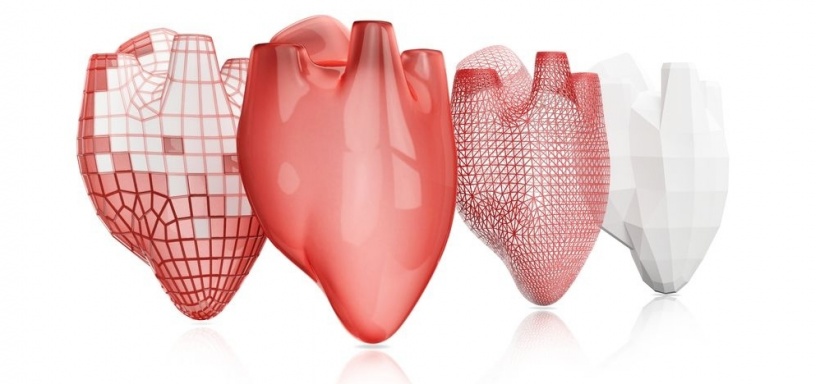

Article • Organ-sized models

Spain takes medical 3-D print to heart

3-D print technology is expanding to cardiology surgery and interventional procedures. Research is scarce in Europe but a group of Spain-based cardiologists are currently developing 3-D print models to assess their value in the heart.

Report: Mélisande Rouger

Everything is new in cardiology, so we need more studies.

Dr. Edwin Tadeo Gómez

Traumatology and maxillofacial surgeons have been using 3-D models to improve their performance for about a decade. Practicing on organ-sized models enables surgeons to prepare for the intervention better than any image, and considerably reduces complications during and after the act. Cardiologists and interventional cardiologists are catching up and a group of specialists in Spain are working to introduce 3-D print in the treatment of congenital heart disease, Dr Edwin Tadeo Gómez Gómez, one of the leading researchers, explained during our interview. ‘Using 3-D models facilitates interventional procedure planning and reduces time of the procedure. Experience shows that it also diminishes complications and errors when calculating the size of devices used in trans-catheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) or when placing MitraClip or Watchman devices in closure of left atrial appendage,’ he said.

Gómez’s company Healtix is working with two organisations, TECHFIT, a Colombia-based specialist in medical 3-D design, and MIZAR, a Spanish company that produces 3-D material – using mainly titanium and thermoplastic – on the project. The group plans to work with different cardiology departments in Madrid to study the educational and clinical applicabilities of 3-D printing.

There is also reason to believe that using 3-D print models beforehand may reduce complications in heart surgery, based on results obtained in traumatology and odontology. In both fields, using 3-D models enables reduction of risk complications by 30 to 40% during surgery, shortens surgery time by half and diminishes hospital stay. But large-scale randomised studies must still be carried out to confirm this potential. ‘Everything is new in cardiology, so we need more studies. In addition, congenital heart disease is rare, affecting only 1% of the population, of whom 30% can benefit from surgical treatment,’ Gómez said.

Simulation would be another area of development in cardiology. 3-D print could significantly shorten the duration of the learning curve, for instance in TAVI interventions. Interventional cardiologists need to perform about 100 procedures to master the technique; however, by being able to practise on 3-D print models, they could need only 70 interventions to prepare. Complications during the learning curve would also be reduced by 50%, according to Gómez.

Last but not least, 3-D print models could serve to design mechanical valves and other devices for each patient, to avoid current issues with size and post surgical complications. ‘In traumatology, evidence shows that artificial hips developed from 3-D print models last longer. Using personalised valves instead of standard devices would boost surgery outcome,’ he said.

3-D medical technology is babbling in Spain. For the moment only Salamanca and Gregorio Marañon hospitals have performed a few closures of left atrial appendage based on 3-D print. Expanding the use of 3-D print technology to cardiology would be a relevant move for the country, where imaging and image analysis are covered by the national public health service. “The most expensive aspect of 3-D technology is imaging and image post processing, which represents about 80% of the total cost. In Spain, MR and CT examinations are entirely covered by the national health service, and image post-processing is done by a radiologist and not a cardiologist, so this saves a lot of money,’ Gómez said. ‘Once the model is ready to become print the intervention could cost between €400 and €1,500, depending on the material used.’

Profile:

Edwin Tadeo Gómez is a cardiologist at Gregorio Marañon University Hospital in Madrid. He has extensive experience with cardiac CT, 3-D trans-oesophageal echocardiography, 3-D post processing in cardiology, especially in congenital and structural heart disease, and interventional cardiac imaging. Born in Medellin, Colombia, in 1981, he worked as an emergency doctor at several hospitals in Colombia before moving to Spain.

08.08.2016