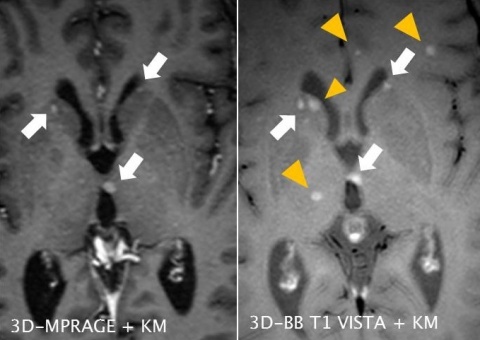

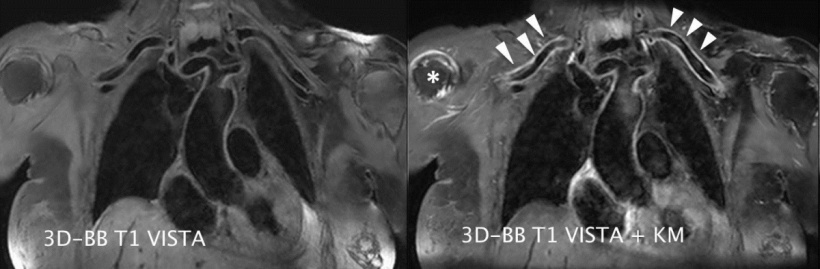

3D-MPRAGE sequence as well as a 3-D-Black-Blood Sequence (arrowed), although several of the white matter lesions detected in the FLAIR sequence show contrast medium absorption in the black-blood sequence that cannot be detected in the conventional sequence (circles). The existence of contrast medium absorption in these lesions shows the degree of disease activity and directly affects the patient’s clinical management.

Article • Black-blood

Seeking time-efficiency and high contrast

Black Blood Imaging may not sound helpful – but it is. The MRI specialist can work with clearer contrasts and gain greater certainty in tumour diagnosis as well as the detection of inflammatory changes in tissue.

Report: Sascha Keutel

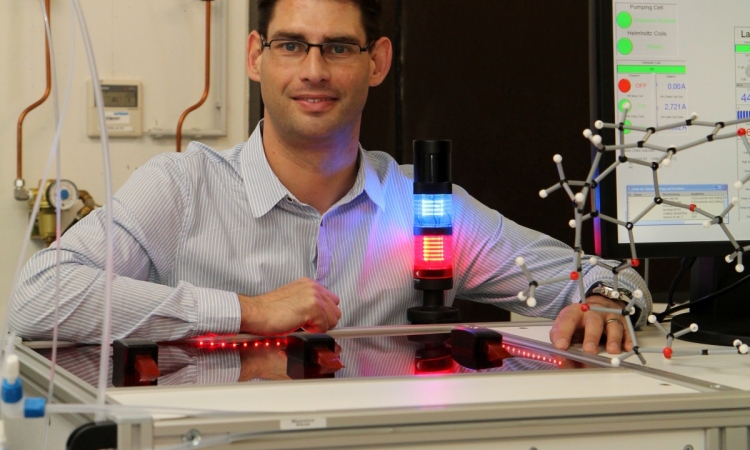

MRI procedures can be divided into those that show blood flow as bright (bright blood) and those that show it as dark (black blood). Although the latter method has numerous advantages compared to conventional imaging it is not yet used in clinical routine, according to Dr Tobias Saam, Head of Magnetic Resonance Imaging at the Inner City branch of the Institute for Clinical Radiology at the Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich.

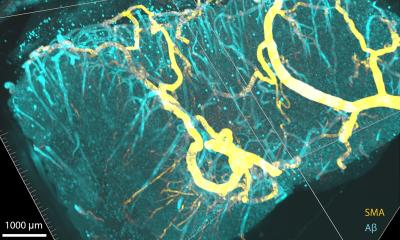

Black-blood sequences primarily visualise the actual walls of the blood vessels rather than blood flow. These sequences are routinely used for cardiac imaging and to identify artery dissections. However, they have great potential in imaging atherosclerotic plaques and inflammatory changes in the vascular walls.

Up to recent years, black-blood sequences could only be shown in 2D, and running these was very complex. ‘It used to take us up to 40-50 seconds to visualise a section of the intracranial vessels of 2mm thickness. It took five to six minutes to acquire a small number of images. A new 3D procedure, which we developed along with Philips Healthcare, now makes it possible to acquire images of the entire head, and with even better resolution, within the same space of time, so the procedure is now much more time efficient,’ Dr Saam explains.

The procedure visualises significantly higher number of masses

The new 3D Black-Blood T1-TSE Sequence does not require prepulse for blood suppression and is therefore particularly time-efficient. In a first study on intracranial tumour imaging Saam’s team showed that the new procedure visualises a significantly higher number of masses compared to conventional sequences. ‘This new 3D black-blood one Tesla sequence with variable flip angles allows us to detect more metastasses than with 3D gradient echo-sequences that are normally used for tumour detection. The difference is significant. The procedure also has fewer flow artefacts than 2D-TSE sequences,’ Saam explains. ‘This is of clinical relevance because the earlier we can detect metastases or lesions the better we can treat them.’

A further effect of the new sequence: With conventionally used gradient sequences blood and lesions appear bright. The black-blood sequence shows masses/lesions brightly, but not the blood, which is shown as dark. ‘This makes it easier to detect lesions, as there is less distraction from bright blood vessels,’ he adds.

Advantages for the visualisation of vascular walls

Vasculitis is a comparatively rare disease often with unspecific clinical symptoms; its early detection poses a particular challenge for all clinicians. Vasculitides are primarily based on changes in the vascular walls. Diagnostic difficulty increases because any luminal changes detected are usually unspecific and they can also manifest as a result of other diseases. Therefore, the validity of conventional imaging procedures is often limited. So far, the gold standard for imaging large vessel vasculitis has been PET-CT. However, Saam sees considerable advantages in the new procedure. ‘Black-blood technology enables us to directly visualise the vascular wall, to it’s possible to detect - at an early stage and with the help of contrast media - thickening of the walls, which can be evidence of atherosclerosis or inflammation of the vascular walls. Therefore we can use the procedure for direct imaging of inflammatory changes of intracranial as well as extracranial arteries.’

Black-blood imaging can reveal central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis

The specialist cites central nervous (CNS) system vasculitis as an example: ‘We cannot visualise this with other imaging procedures. In this case, black-blood imaging is the only procedure that makes this possible. This capability has recently caused a lot of interest amongst neurologists,’ Saam points out. ‘Although this still has to be evaluated in larger studies, the procedure definitely has potential. ‘We are already having patients referred to us whose doctors are excited about it.’

Profile:

Tobias Saam studied medicine at Heidelberg University where he also gained a doctorate in 2003. In July 2010 he wrote his habilitation on ‘Methodical Development and Clinical Evaluation of High Resolution MRI of Atherosclerotic Plaques in the Carotid Arteries’. Since 2006, Dr Saam has worked at the Institute for Clinical Radiology at the Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU) in Munich and has headed Magnetic Resonance Imaging since 2013. His numerous honours for work on MRI use to detect atherosclerotic plaques include the Coolidge Award.

16.04.2015