The findings suggest that policymakers in low-income and middle-income countries may need to re-examine the burden and impact that dementia places on their health services.

As the average age of the global population increases, dementia and other age-related illnesses are increasing in prevalence. Recent estimates have suggested that over 24 million people live with dementia worldwide, with 4.6m new cases every year. However, a number of studies have suggested that the prevalence of dementia in the developing world is between a quarter and a fifth of that typically recorded in developed countries.

Now, research announced at the International Conference on Alzheimer's Disease and published online today in the journal The Lancet suggests that this figure has been underestimated and that levels of dementia in the developing world may be much closer to those in the developed world.

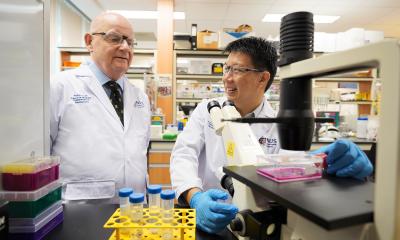

The research was conducted by the 10/66 Dementia Research Group, an international collaboration whose funders include the Wellcome Trust. The 10/66 Dementia Research Group is part of Alzheimer's Disease International. The group is so named because less than one tenth of all population-based dementia research has been directed towards the two-thirds or more of all people with dementia who live in developing parts of the world. It aims to provide by far the most extensive source of information regarding dementia in low- and middle-income countries.

Professor Martin Prince from the Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, who leads the group, believes that a number of factors may have led to researchers failing to identify a significant proportion of cases of dementia.

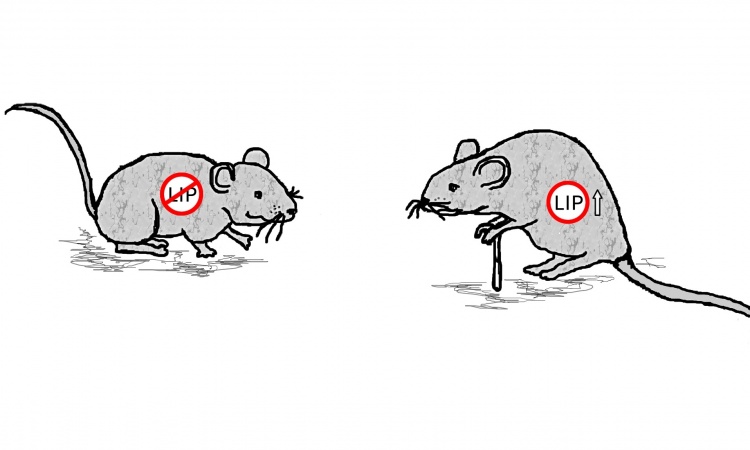

"It's likely that cultural differences may be partly responsible for researchers missing cases of dementia," says Professor Prince. "Our evidence suggests that relatives in developing world countries are less likely to perceive or report that their elders are experiencing difficulties, even in the presence of clear evidence of disability and memory impairment."

The research group assessed almost 15 000 people over the age of 65 in 11 countries, including India, China, Cuba and Peru. The assessment consisted of interviews with the participant and, typically, a family member, as well as a physical examination and a blood test. The criteria used by the 10/66 researchers were developed and validated cross-culturally across Latin America, Africa, South and South-east Asia in an attempt to enable valid comparisons to be made between different countries and cultures even when a high proportion of older people had received little or no education.

According to the study, prevalence of dementia in urban settings in Latin America is comparable with rates in Europe and the US, though the prevalence in China and India is lower.

Dementia leads to associated disability, such as memory impairment, affecting the quality of life of the patient. However, pilot studies carried out by the group suggest that dementia also places a high burden on the carer and that this is exacerbated by lack of knowledge of the disease and its likely progression.

"You could question the point of labelling someone as having dementia if their relatives do not acknowledge it as a problem," says Professor Prince. "Our data suggest that even if it is not recognised as dementia, the illness places a heavy burden on both the elderly patient and their relatives. Being able to estimate accurately the true population of people living with burden is the first important step towards putting into place appropriate health and social care systems."

The 10/66 investigators are now analysing their data to examine the burden and impact of dementia in different countries, relative to that of other chronic diseases. This will include the effect of dementia on disability, dependency, strain on the carer, and the economic cost of dementia and other diseases. These data, in conjunction with the prevalence estimates now published, will enable policymakers in low-income and middle-income countries to prioritise more effectively, as they begin to invest more heavily in the prevention and control of chronic non-communicable diseases.

The research has been welcomed by Marc Wortmann, Executive Director of Alzheimer's Disease International, which supports the 10/66 Dementia Research Group.

“Behind every case of dementia, there are relatives who are also affected, and both patients and carers need support," says Mr Wortmann. "Alzheimer’s Disease International hopes that the World Health Organisation will use these findings to make raising awareness of and tackling dementia a priority in all parts of the world."