rfMRI reveals mind moving matter

Exploring how the human brain operates

‘We finally have tools to non-invasively study the human brain in normal subjects and diseased patients,’ says Professor Stefan Sunaert, Head of Translational MRI at the Department of Imaging & Pathology, Leuven University Hospital (Belgium)

The technology that enables us to perform such ground-breaking studies is functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or, more precisely, resting fMRI (rfMRI), the most recent further development of fMRI that visualises brain function.

rfMRI can show and quantify the brain regions involved in a certain process. ‘But how the brain works exactly is something we still need to discover and learn in order to understand disease,’ points out Prof. Sunaert, who chaired the New Horizons Session Imaging of the mind at ECR 2013.

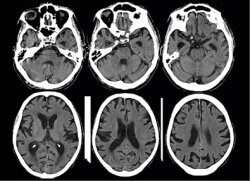

Resting brain activity is identified by visually examining changes in brain perfusion. The MRI procedure uses the different degrees of magnetisation of oxygen-poor venous and oxygen-rich arterial blood to create a blood oxygen level dependent signal (BOLD). Based on this signal, brain activity can be visualised and displayed in a colour code. Every activity of the brain is associated with a BOLD signal. Thus, the functional organisation of a brain and its changes caused by disease can be examined. Unfortunately, the signal is buried under ‘noise’. ‘It took us a long time to prove that the noise is not only artefacts but that it covers the BOLD signal, which indeed correlates to certain brain activities,’ Prof. Sunaert explains.

The research on resting-state functional connectivity unearthed a number of networks, of patterns of synchronous brain activities: the executive control component, sensory/motor component, auditory component, up to three different visual components, two lateralised frontal/parietal components and the temporal/parietal component. The elements of these networks are located in different brain regions and, in a healthy person, these are always simultaneously active.

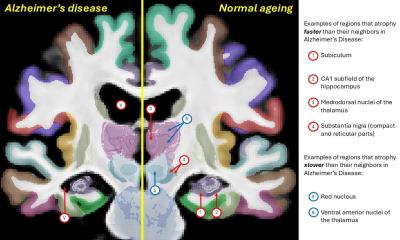

A network that is already particularly well understood is the default mode network (DMN), a web of brain regions that becomes active when a person is awake but in a state of calm. It is activated by reflection, remembering or daydreaming and it correlates negatively with other networks involved in the visual perception of the outside world. The DMN activity changes over time. ‘With age, the network connectivity decreases. And that is also what happens in Alzheimer’s disease,’ explains Professor Andrea Falini, Head of Neuroradiology at the Istituto Scientifico San Raffaele in Segrate near Milan. Falini’s research focuses inter alia on the differences between natural ageing processes and the development of Alzheimer’s – which all occur in the DMN – aiming for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. ‘Early diagnosis is mandatory for new therapeutic strategies,’ the Italian neuroradiologist stresses.

Some neuroradiologists are apprehensive about possible abuses of rfMRI; for example, ECR chairman Prof. Sunaert mentioned several applications he finds personally very disconcerting: In one fMRI-based study the neural responses of children in connection with markers were examined. Results confirmed that food logos activate some brain regions in children known to be associated with motivation.

Professor Sunaert also pointed out that a US company claims to be able to use BOLD signals to tell lies from truth, a modern version of the lie detector. ‘That’s really scary,’ the professor said, shuddering. ‘Would you undergo an fMRI exam if the technology were able to identify lies or erotic thoughts?’ he asked the audience. Not one participant raised a hand.

03.07.2013