News • New study

Rethinking the six-hour rule for stroke victims

Neurologist who coined the phrase "Time is Brain" says message is not so simple anymore. Rather there should be no hard-and-fast rule governing when therapy can be given because strokes progress differently in different patients.

In 1993, neurologist Camilo R. Gomez, MD, Loyola Medicine, coined a phrase that for a quarter century has been a fundamental rule of stroke care. "Unquestionably the longer therapy is delayed, the lesser the chance that it will be successful," Dr. Gomez wrote in an editorial 25 years ago. "Simply stated: time is brain!"

But the "time is brain" rule is not as simple as it once seemed, Dr. Gomez now argues in his most recent paper, published in the August 2018 Journal of Stroke & Cerebrovascular Diseases. Dr. Gomez is a Loyola Medicine stroke specialist and nationally known expert in minimally invasive neuroendovascular surgery.

It is still true that stroke outcomes generally are worse the longer treatment is delayed so it remains critically important to call 911 immediately after the first signs of stroke. But, Dr. Gomez reports, the effect of time can vary greatly among patients. Depending on the blood circulation pattern in the brain, emergency treatment could greatly help one patient, but be too late for another patient treated at the same time. "It's clearly evident that the effect of time on the ischemic process is relative," Dr. Gomez wrote.

About 85 percent of strokes are ischemic, meaning the stroke is caused by a blood clot that blocks blood flow to an area of the brain. Starved of blood and oxygen, brain cells begin dying.

"It is no longer reasonable to believe that the effect of time on the ischemic process represents an absolute paradigm."

Camilo R. Gomez

Traditionally, there was little physicians could do to halt this ischemic process, so there was no rush to treat stroke patients. But in his groundbreaking editorial, Dr. Gomez wrote that rapid improvements in imaging technologies and treatments might enable physicians to minimize stroke damage during the critical first hours. "It is imperative that clinicians begin to look upon stroke as a medical emergency of a magnitude similar to that of myocardial infarction (heart attack) or head trauma," he wrote.

As new treatments such as the clot-busting drug tPA became available, doctors did indeed begin treating strokes as emergencies. In select patients, intravenous tPA was shown to stop strokes in their tracks by dissolving clots and restoring blood flow. Initially, tPA was recommended in select patients within three hours of the onset of symptoms. This therapeutic window later was lengthened to 4.5 hours.

But Dr. Gomez said there should be no hard-and-fast rule governing when therapy can be given because strokes progress differently in different patients. Time is not the only important factor. Also critical is the blood circulation pattern in the brain.

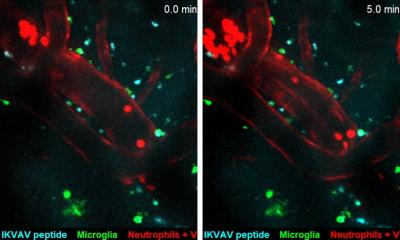

After an ischemic stroke strikes, a core of brain tissue begins to die. Around this core is a penumbra of cells that continue to receive blood from surrounding arteries in a process called collateral circulation. Collateral circulation can keep cells in the penumbra alive for a time before they too begin to die. Good circulation slows down the rate at which the cells die.

In his latest project, Dr. Gomez used computational modeling to identify four distinct types of ischemic stroke based on the collateral circulation. "It is no longer reasonable to believe that the effect of time on the ischemic process represents an absolute paradigm," Dr. Gomez wrote. "It is increasingly evident that the volume of injured tissue within a given interval after the time of onset shows considerable variability, in large part due to the beneficial effect of a robust collateral circulation."

Dr. Gomez added that this computational modeling "represents a first step in our journey to enhance clinical decisions and predictions under conditions of considerable uncertainty."

Source: Loyola University Health System

14.08.2018