Article • Integrated diagnostics

Radiologists, pathologists and geneticists gather around a digital table

Radiology, pathology, medical genetics and laboratory medicine under one roof: many hospitals are toying with the idea of ‘integrated diagnostics’ but it was the medical management at Geneva’s University Hospital that dared to take the first step and consolidate all these diagnostic disciplines in a single organisational unit: The Diagnostic Department.

Report: Daniela Zimmermann and Michael Krassnitzer

‘Our long-term vision is a “diagnostic board” within which radiologists, pathologists and geneticists collaborate to create a detailed and structured diagnosis that goes far beyond mere imaging,’ underlines Christoph Becker, Emeritus Professor at the University of Geneva and, until 2019, Head of Radiology at the University Hospital Geneva.

In Geneva, joining these disciplines was above all an administrative-organisational procedure, the Swiss radiologist explains. This is not about radiologists doing the pathologists‘ work, or vice versa, he emphasises: ‘We aim to do away with the insular approach of the diagnostic disciplines and arrive at a closer cooperation of the diagnostic specialists.’

Integrate diagnostics – how?

Becker considers three aspects are crucial for diagnostics integration, first the organisational-administrative aspect. Since this is determined to a large extent by local factors – such as geography; the hospital’s organisational structure; distances between departments; budget – no general recommendations can be made. The second aspect is the digital infrastructure where, as Becker points out, significant differences need to be taken into account: ‘Radiology launched the digitisation project 20 years ago and thus is almost fully digitised. In the lab, digitisation has also progressed very well.’ Pathology, however, has only recently begun to digitise, one reason being the sheer complexity of the endeavour.

‘Whilst today, radiology images are digital from the beginning, a tissue sample is, obviously, analogous. ‘The analogous sample and all necessary analytical steps have to be digitised. This requires much more computer power, since colour and high resolution are basic requirements,’ Becker points out. In Geneva, the first steps towards digital pathology and a comprehensive digital infrastructure for the entire medical imaging complex are currently being implemented. A central digital archive is planned in which all acquired image data in the University Hospital are stored – radiology images as well as images and videos created in other departments, e.g. dermatology, or images from endoscopies.

Successful workflow

The third crucial aspect of integrated diagnostics is a workflow that allows to identify and remove discrepancies in diagnostic procedures: today it may well happen in complex clinical situations that different diagnostic disciplines arrive at different conclusions in their assessment of findings. This should be avoided by intelligent diagnostic processes aiming at a synthesis of the diagnostic findings: Diagnostic specialists and their tools must be able to communicate more directly about discrepancies in their assessment.

A first small step was made several years ago at the University Hospital of Geneva. ‘During an image guided biopsy in the radiology department, a pathologist is present and has access to the necessary technical infrastructure for staining and microscopic evaluation in order to assess the sample right away for its quality. If the sample is insufficient, or cannot be used for whatever reason, a second sample is taken immediately. ‘The pathologists like being on site because they appreciate the direct communication with colleagues. The patients also benefit because they don’t have to come back for a second biopsy,’ Becker explains.

A specialist’s time is very valuable, and the time spent to align the different complex diagnostic findings during the tumour board meeting reduces the number of patients who can benefit from common decisions

Christoph Becker

Today, treatment strategies for individual patients are often decided jointly in multidisciplinary meetings including all necessary clinical specialists. Typical examples are the tumour boards in oncology. ‘These tumour boards are time-consuming and difficult to organise,’ the radiologist points out, ‘because to get the different specialists to meet at a certain time, at a certain place, is not easy. A specialist’s time is very valuable, and the time spent to align the different complex diagnostic findings during the tumour board meeting reduces the number of patients who can benefit from common decisions,’ Becker underlines. Therefore, discrepancies between the findings of the individual diagnostic disciplines should be identified early on and resolved before the tumour board convenes. ‘Ideally, radiologists, pathologists and other diagnostic specialists should provide a consensual integrated diagnostic report, which is then the input for the tumour board,’ Becker explains. ‘While this might not be necessary in all cases, he adds, ‘it will be very useful in many special and complex cases, with a clear benefit to both treating physicians and patients’.

Radiologists and pathologists should learn to communicate

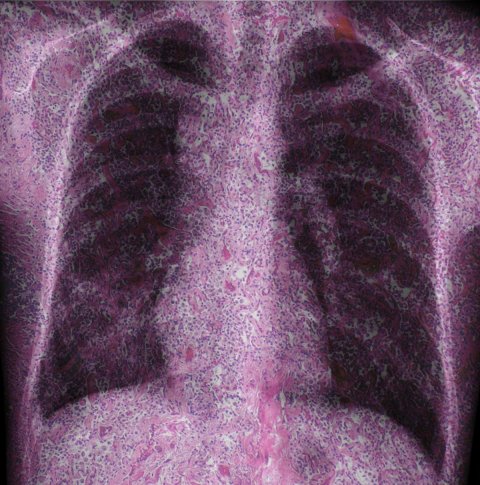

Image source: Nephron, Desquamative interstitial pneumonia -- low mag, Mashup by HiE/Behrends, CC BY-SA 3.0

Communication: this is easier said than done because, in a way, radiologists and pathologists speak different languages. While radiologists and macroscopic pathologists both assess morphology, they look at the issue at hand from very different vantage points. Radiology strives to offer an overview of body regions or organs; pathology in turn offers insights that are anatomically less comprehensive but – with the help of a microscope – go deeper to the cell and immunology level. Evaluating the results of each of these methods in a separate or ‘insular’ way can be misleading, due to the heterogeneity of tumours. For a best possible diagnostic workup it is therefore imperative to look at the complementary data in a joint context. ‘Having said that, we must also point out that modern technology increasingly enables radiologists to look at deeper-lying features of tissue structures,’ Becker concedes, adding that functional imaging has now become routine. For instance, CT perfusion shows how fast tissue takes up blood; diffusion-weighted MRI offers insights into the cellular level of the tissues, and positron-emissions tomography (PET) provides information on metabolic activities, such as glucose consumption. ‘MRI parameters, such as T1 or T2, enable us to interrogate tissue with different non-invasive parameters,’ Becker points out, adding that all data ‘need to be merged to be able to understand a patient’s exact status’.

Patient empowerment on the rise

Speaking of the patient, Becker is deeply convinced that, in the future, patients will be increasingly involved in decision-making. ‘Patients of the younger generations want to know what’s going on. Some want to be present when their case is discussed and when further steps are decided. They want to hear arguments; ask questions. In Geneva, even today some patients take part in the tumour board meeting on their case.’ This concept of ‘patient empowerment’ can be summarised with the modern slogan ‘nothing about me without me’. Studies have shown that patients, above all younger ones and women, with online access to their electronic patient records, call up their radiology findings more often than any other clinical documents.

However, patient empowerment also raises questions: when findings become ever more detailed and complex, when parameters are included that only specialists can decode, how can patients understand the findings? ‘Enter artificial intelligence,’ Becker suggests, with a smile. Why not have algorithms translate the highly complex findings in layperson’s terms, he asks. This seems the only viable solution because, as he points out, ‘manually translating these findings and integrating them in routine clinical workflow is so time-consuming that it can be done only with the help of computers.’

Profile:

Professor Christoph D Becker gained his medical doctorate and specialist radiology training at Berne University, Switzerland, followed by a two-year clinical fellowship in interventional radiology at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. He returned to Berne University Hospital as a staff radiologist and also acquired his university teaching licence. In 1994, he joined Geneva University Hospital to become head of Interventional and abdominal radiology. In 2001, he was appointed as tenured professor and Vice Director of the hospital’s radiology clinic, followed by an appointment as Director in 2004. As a full professor he also chaired the clinical department of medical Imaging and the academic department of radiology and medical informatics of the faculty of medicine. He was involved in setting up the new clinical diagnostics department. In 2019, following the end of his tenure as professor and director of the clinical and university departments he became an Emeritus Professor of the University of Geneva.

12.03.2020