Article • Diagnostic toolkit

New cardiac genetic testing panels

As new cardiac genetic testing panels become available, cardiologists have been warned not to lose sight of the importance of comprehensive clinical evaluation. While genetic testing is helping to identify more people at risk of inherited conditions, experts stress they are only part of the diagnostic toolkit.

Report: Mark Nicholls

This was outlined in a session entitled ‘The new cardiac genetic testing panels: implications for the clinical cardiologist’ held during the British Cardiovascular Society Conference in Manchester this June. With the emergence of new genetic tests for cardiac disease, Professor Cliff Garratt raised issues ‘the cardiologist needs to know’ in making the modern diagnosis.

Sanger Sequencing remains the standard to confirm a single genetic variant but new tests – next generation sequencing – which can be applied to a large number of genes, are now facilitating more testing, more cheaply and in the same timescale with panels of genes.

Garratt, who is Professor of Cardiology at the Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, Professor of Cardiology at Manchester University and Hon Consultant Cardiologist at Central Manchester University Foundation Trust, explained: ‘We can have them highly targeted at 5-15 genes for LQT, for example, or a less targeted panel for 20 genes, though the disadvantage of the panel approach is that you have the problem of background genetic noise.’

Advances in genetic and genomic technology are enabling many more patients with a rare disease to benefit from genetic tests, either to establish or confirm a diagnosis; or assess the genetic status of other family members and gene panel tests are now making it possible to test simultaneously all the genes known to be associated with a condition.

Despite having the benefits of genetic testing, Garratt issued a clear warning that, whilst genetic testing is proving valuable, it is not an alternative to making a clinical diagnosis. ‘It will not solve your clinical problems but will help management of patients who you have a proper diagnosis for,’ he said.

During the same session Dr Shehla Mohammed outlined the work of the UKGTN (United Kingdom Gene Testing Network) in the evaluation process for genetic tests. The role of UKGN is strategic; it involves healthcare commissioning and evaluating new genetic tests for clinical utility and validity with screening for 698 disorders, 872 genes and 46 panel tests. ‘It’s about promoting equity of access of genetic tests for individuals who have, or are, at risk of genetic disorders,’ Mohammed explained.

UKGTN works with 30 member laboratories across the UK, many affiliated to regional genetic centres and some linked with specialist services and follows the ACCE model process for evaluating genetic tests of: Analytic Validity; Clinical Validity; Clinical Utility; and Legal and Ethical and Social implications. ‘The reasons for doing genetic testing is for diagnosis, treatment, prognosis and management, pre-symptomatic diagnostic testing and genetic risk assessment,’ Mohammed added. ‘The UKGTN promotes high quality, equitable and appropriately identified genetic tests.’ It has the capability to deliver effective cascade testing in inherited cardiac disorders.

Genetic testing is probabilistic and forms part of a comprehensive clinical evaluation

Kay Metcalfe

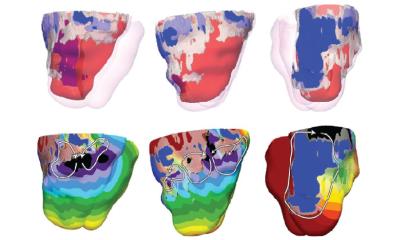

Dr Kay Metcalfe, NHS Consultant Clinical Geneticist at St Mary’s Hospital Manchester, discussed panel testing for Sudden Cardiac Death SCD syndromes. Underlining Garratt’s point, she added: ‘Family screening helps identify those at risk, but the challenges of the exome and genome sequencing approach are the large amount of data generated. Genetic testing is probabilistic and forms part of a comprehensive clinical evaluation.’

Dr Paul Clift, from Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham, spoke about genetic testing in the context of Marfan syndrome and other familial thoracic aortic aneurysm syndromes but stressed the importance of physical and clinical assessment in such conditions in association with genetic testing. According to Clift, Marfan remains a clinical diagnosis but fibrillian-1 (FNB1) gene testing aids that diagnosis and there are advantages with panel testing giving rapid genotyping allowing a detailed management strategy for patients. ‘Panel testing in aortopathy allows for early genotyping for suspected hereditary aortopathy, risk stratifies management strategy for patients and families.’

Profile:

Cliff Garratt is Professor of Cardiology at the Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, Professor of Cardiology at Manchester University and Hon Consultant Cardiologist at Central Manchester University Foundation Trust. His research and clinical interests focus on the mechanisms and management of atrial fibrillation and familial sudden cardiac death syndromes. He is co-chair of the Heart Rhythm UK Working group on Clinical Management of Familial Sudden Death syndromes and Vice-President (Education and Research) of the British Cardiovascular Society.

31.08.2015