MERS-CoV: Global action needed?

With so much unknown about the pathogenicity of the virus, fears spread over transmission during massive religious gatherings

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recently formed an international emergency committee to decide whether Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) should be ascribed Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) status, amid reports of a lack of information from the worst affected countries.

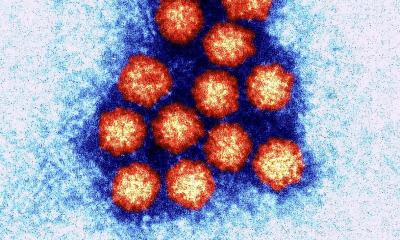

Source: NIAID/RML

The 15-strong committee of experts will report to WHO’s Director General with technical advice to determine whether MERS-CoV requires the PHEIC, in which case the committee would recommend temporary global measures to control the spread of the virus. MERS-CoV has already killed more than 50% of the 80 people it has infected in nine countries.

The first emergency talks on the virus coincided with the start of Muslim festival Ramadan, when more than two million international pilgrims make the Umrah pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia – where 66 cases have been recorded. Another mass gathering in Saudi Arabia this October, the Hajj, attracts more than three million pilgrims, which will put MERS-CoV transmissibility to its greatest test.

The committee heard a review of the situation from the WHO Secretariat and briefings from representatives of countries where MERS-CoV has occurred. However, the Director General announced that the committee was to reconvene on 17 July because ‘additional information was needed in a number of areas’.

The lack of available information on the virus is explained by a short supply of samples, according to Professor Christian Drosten, Head of the Institute of Virology at the University of Bonn Medical Centre. ‘European labs have driven the process, from the discovery of the virus to the development of diagnostic tools and the development of first recommendations for clinical treatment,’ he explained. ‘However, no samples have arrived in Europe from any affected Middle Eastern countries… The gap is really in the epidemiological field, where research has to be done in – and supported by – the affected countries.’

Professor Drosten has identified the first virulence factor, an interferon induction antagonist, and is now focusing on how and where the virus is spreading and trying to locate its source. ‘We’re working on a few samples from imported cases in Germany and we’ve conducted a small collaborative study with a lab in Saudi Arabia.’ However, he added: ‘Much more would have to be done, with more than one pair of collaborating labs.’

Although the first case was diagnosed in Spring 2012, medical professionals still did not know what the animal reservoir is or why people are becoming infected. In its rapid risk assessment dated 18 June, The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control said: ‘It is unusual to have such a degree of uncertainty at this stage in an outbreak.’

A limited human-to-human transmission

The virus displays limited human-to-human transmission mainly within families, in hospitals (patient-to-patient and patient-to-healthcare worker), and sporadic infections are occurring in towns and villages. A research report from Johns Hopkins University found that MERS-CoV is easily transmitted in a healthcare setting, based on studies in four Saudi Arabian hospitals, one of which was the source of several infections linked to dialysis patients.

However, the pattern is changing. While symptoms usually include severe acute respiratory infection, eight recent cases in Saudi Arabia were asymptomatic. And although the virus has mostly infected elderly individuals, particularly men, four of the eight were female healthcare workers and the other four, children aged between seven and 15 years.

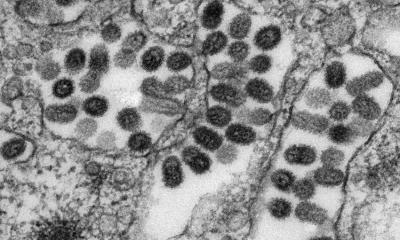

Several European labs continue to investigate the virus, many of which worked on the closely related SARS-CoV, which broke out a decade ago, although it had a much lower death rate of 9%. ‘We will have a load of valuable data from the research field coming out this year,’ Professor Drosten predicts.

Update: MERS-CoV found in dromedary camels

Antibodies specific to MERS-CoV has been found in dromedary camels, according to research published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

An international research team led by Dr Chantal Reusken, at the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment in Bilthoven, the Netherlands, gathered 349 blood serum samples from livestock in various countries (Oman, the Netherlands, Spain, Chile), which included dromedary camels, cows, sheep, and goats, as well as some animals closely related to dromedaries.

The blood serum samples were analysed for the presence of antibodies specific to MERS-CoV, as well as antibodies reactive to SARS coronavirus, and another strain of coronavirus labeled HCoV-OC43, which can also infect humans and is closely related to a bovine form of the virus.

The Netherlands researchers found no evidence of cross-reactivity between antibodies for MERS-CoV and those for SARS or HCoV-OC43, confirming those findings using highly specific virus neutralisation tests.

The results suggest that the presence of MERS-CoV specific antibodies is likely to indicate previous infection with MERS-CoV, or a closely related virus, at some point in the animal’s history.

No MERS-CoV antibodies were found in blood serum taken from 160 cattle, sheep, and goats from the Netherlands and Spain. However, antibodies specific to MERS-CoV were found in all 50 serum samples taken from dromedary camels in the Oman – samples originating from a number of several locations there, suggesting that MERS-CoV, or a very similar virus, is circulating widely in Oman’s dromedary camels.

Lower levels of MERS-CoV-specific antibodies were also found in 14% (15) of serum samples from two herds of dromedaries (105 camels in total) from the Canary Islands, not previously known to be a location where MERS-CoV is circulating. No antibodies specific to the virus were detectable in tests on 34 animals closely related to the dromedary, such as Bactrian camel, alpaca and llama sampled in the Netherlands and Chile.

‘The dromedary camels that we tested from the Middle East (Oman) were more often positive and had much higher levels of antibodies to MERS-CoV than the dromedary camels from Spain,’ the researhers pointed out. ‘The best way to explain this is that there is a MERS-CoV-like virus circulating in dromedary camels, but that the behaviour of this virus in the Middle East is somehow different to that in Spain.

‘As new human cases of MERS-CoV continue to emerge, without any clues about the sources of infection except for people who caught it from other patients, these new results suggest that dromedary camels may be one reservoir of the virus that is causing MERS-CoV in humans. Dromedary camels are a popular animal species in the Middle East, where they are used for racing, and also for meat and milk, so there are different types of contact of humans with these animals that could lead to transmission of a virus.’

The team called for further animal studies for MERS-CoV in the Middle East, to identify the virus that triggers these antibodies in dromedaries, and compare this with the virus from human cases. It also urged follow-up of new human cases to gather information about patients’ contacts with animals and animal products, such as camel milk.

Further details: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(13)70164-6/abstract

Profile:

Christian Drosten MD is Professor of Virology and head of the Institute of Virology at the University of Bonn Medical Centre, Germany. He studied medicine at the University of Frankfurt/M Medical School and joined the Virology Department at the renowned Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, where, in 2002, he became laboratory head for Molecular Diagnostics before accepting his current role in 2007. The Institute’s diagnostic laboratories serve a 1,300-bed University hospital, covering all human viruses with a full spectrum of diagnostic techniques and strong focus on molecular diagnostics. Research focuses on emerging viral diseases, using coronaviruses, alphaviruses and flaviviruses as main model organisms.

26.08.2013