Vulnerable plaque imaging

Looking for the perfect modality

What's the ideal solution for vulnerable plaque imaging? 'A non-invasive imaging procedure with high spatial and temporal resolution, and without radiation exposure, and which provides information on coronary plaque composition precisely and in series.'

Report: Axel Viola

Quite a tall order, as Prof. Grigorios Korosoglou is well aware. Whilst this perfect method is not – yet – available ‘it would enable us to determine whether and where vulnerable plaques have accumulated, meaning plaques that are at risk of rupture and which will most likely cause a myocardial infarction within the next few years.’

Today, there is no method available to detect vulnerable plaque, not even at the department of cardiovascular imaging at Heidelberg’s University Hospital, which is headed by Prof. Korosoglou. ‘Coronary angiography shows stenoses and is the current gold standard in the diagnosis of coronary heart disease. But there is no modality that can tell us which plaque is unstable and thus a potential source of a future cardiac event such as a myocardial infarction.’

Currently, interventional or surgical therapy for patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) is geared towards obstructive lesions: only those lesions are treated which significantly narrow the coronary artery lumen. ‘But today we know that a myocardial infarction is not necessarily caused by these lesions,’ Prof. Korosoglou explains, ‘but by those which were not considered significant in angiography.’

While certain diagnostic procedures can identify potentially dangerous plaque based on plaque morphology, most of these techniques are ‘not clinically established’, Prof. Korosoglou underlines, ‘such as intravascular ultrasound, known as IVUS. This invasive procedure is based on virtual histology to identify plaque with a large necrotic core and spotty calcifications. Studies have indicated that a large necrotic core correlates with plaque at risk of rupture.’

Cardiac CT is used routinely to classify patients with suspected CHD and is considered by the European Society of Cardiology to be a modality that will play an increasingly significant role. Cardiac CT is particularly useful because it not only visualises stenosis but also allows the characterisation of the coronary artery walls and the composition of atherosclerotic plaque. Recent CT studies have indicated that patients with a high number of non-calcified so-called low attenuation plaques have a significantly higher risk for future cardiac events, such as a myocardial infarction or sudden cardiac death.

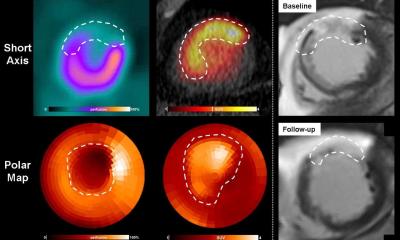

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another modality which might offer the possibility to identify vulnerable plaque but it also is, as the Heidelberg-based cardiologist explains ‘still in the experimental stage. There is for example the attempt to use iron-containing nanoparticles in MRI to visualise inflammation-rich plaques. Plaque macrophages take up the intravenously applied nanoparticles. Thus MRI provides information on the accumulation of macrophages in the plaque which is considered a surrogate parameter for plaque instability and by extension unstable cardiovascular disease.’ MRI, however, still has certain technical limitations: the spatial resolution of the MRI scans is not yet sufficient to provide detailed images of the coronary plaques.

There is another high potential among the imaging modalities, as Prof. Korosoglou points out: ‘Fluorine-18 positron emission tomography combined with computed tomography, known as PET/CT, might become clinically relevant.’ Fluorine-18 is a radiotracer that was previously used to visualise bone formation. Recent clinical studies with acute myocardial infarction patients have shown increased fluorine uptake in ruptured plaques. Moreover increased fluorine uptake was reported in patients with seemingly stable CHD – in exactly those plaques that had been classified as particularly at risk of rupture according to the IVUS scores.

Thus PETC/CT might be a non-invasive modality to detect plaques at risk of rupture or even the early stages of the rupture before the cardiac event – the infarction – happens. Not all plaques, however, take up fluorine-18: particularly patients with a high degree of calcification seem to be metabolically inactive with regard to fluorine-18.

‘These very different approaches show that there are many aspects of atherosclerosis which we have not yet understood. We used to think, for example, that the degree of calcification correlates directly with the risk of a future cardiovascular event. Today we know it might be possible that only moderately calcified and metabolically active plaques are those with the high risk of rupture,’ he summarises. Conclusion in a nutshell: There is much work to be done in atherosclerosis research.

PROFILE:

Professor Dr Grigorios Korosoglou has headed Cardiac CT in the Internal Medicine and Cardiology Department at University Hospital Heidelberg since 2010. In 2012 he also became head of Cardiac MRI there and was also appointed Deputy Medical Director of the Department of Cardiology and Angiology at GNR Clinic Eberbach.

03.12.2014