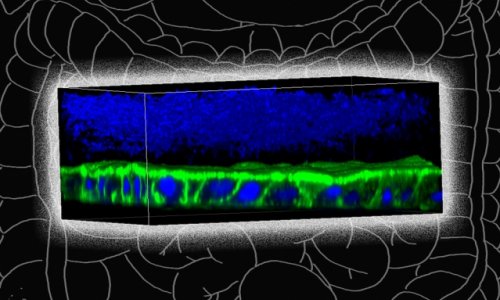

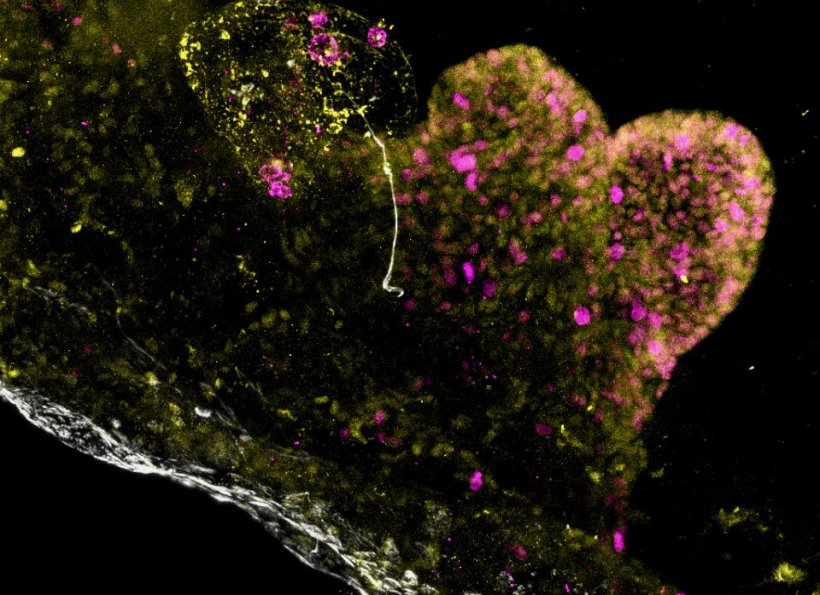

Image source: Jones BC, Benedetti G, Calà G et al., Nature Biomedical Engineering 2026 (CC BY 4.0)

News • Gastric multi-regional assembloid

Lab-grown mini-stomachs to boost understanding of rare diseases

Researchers at University College London (UCL) and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) have developed the first-ever lab-grown mini-stomach that contains the key components of the full-sized human organ.

Known as a multi-regional assembloid, the pea-sized mini-stomach is the first to contain the fundic region (the upper portion of the stomach), the body (the central region where food is mixed with acid and enzymes), and the antrum (the lower part of the stomach that breaks down food before entering the small intestine). These components form the mucosa, the inner surface of the stomach, which is essential for acid digestion, protection against auto-digestion and hormone regulation.

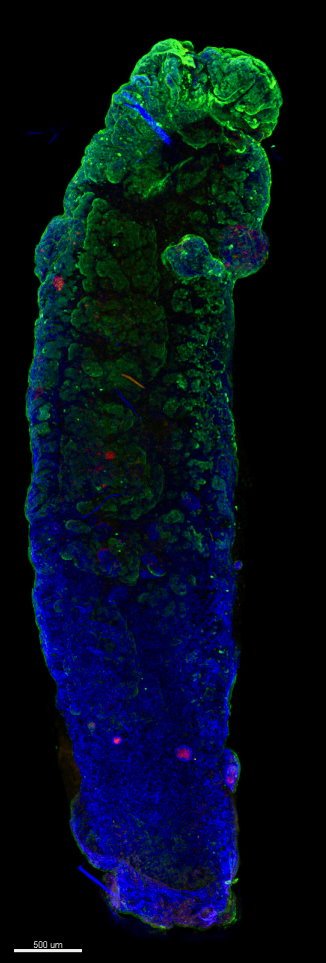

In a paper published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, the researchers explain how they isolated stem cells from patient stomach samples and grew them under special laboratory conditions in a petri dish to create mini-stomachs, known as organoids, that mimic the behaviour of a human stomach.

Image source: adapted from: Jones BC, Benedetti G, Calà G et al., Nature Biomedical Engineering 2026 (CC BY 4.0)

They grew separate organoids for each of the three main stomach regions and then combined – or “assembled” – them into a single version, known as an assembloid version. This is the first time this has been successfully achieved.

The research team found that not only did each component part retain the characteristics of the area of the stomach from which it was grown, but those component parts communicated with each other in the same way that the full-sized human organ does. The assembloids were also able to produce stomach acid, which is a key function of the stomach and helps the body digest food. Researchers then used this technique to model a very rare genetic stomach disease, which they say could open up the possibility of using the system to study more common gastric disorders that have so far been poorly understood.

Senior author Dr Giovanni Giobbe (UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health) said: “Traditional organoids and animal models fail to replicate the regional architecture and functional diversity of the human stomach. Recent advances in gastric assembloid technologies offer the potential to model region-specific physiology and disease phenotypes in vitro. Our multi-regional gastric assembloids replicate the antrum-body-fundus structure and function, including acid secretion, and are uniquely positioned to unravel disease mechanisms in rare gastric disorders.”

Co-Senior author Professor Paolo De Coppi, UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health and a consultant paediatric surgeon at GOSH, said: “With these newly developed miniature stomachs, we have now been able to test treatments for a very rare gastric condition. But these are just preliminary findings and more research is required. This is a major step forward and could have implications for much more common diseases of the stomach lining, which millions of people suffer from.”

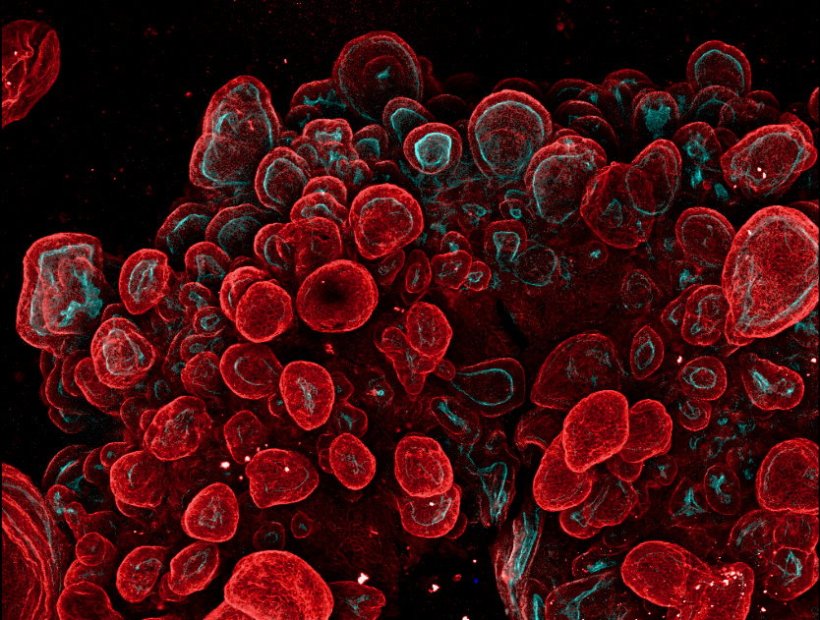

After confirming that the assembloid model worked, the researchers grew multi-regional mini-stomachs from the stem cells of children with a very rare stomach disease called Phosphomannomutase 2-associated Hyperinsulinism with Polycystic Kidney Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (PMM2-HIPKD-IBD). Some children with this condition not only have problems with their kidneys and blood sugar but also show unusual changes in their stomachs, suffering from antral foveolar hyperplasia. These changes include the growth of small lumps (growths), which may lead to bleeding, inflammation, or even increase the risk of stomach cancer. These growths form because of problems with how stomach cells function.

Image source: Jones BC, Benedetti G, Calà G et al., Nature Biomedical Engineering 2026 (CC BY 4.0)

The mini-stomachs allowed the researchers to test their hypothesis about what causes the disorder and to test possible treatments. The benefits of testing treatments in this way should include reducing how long it could now take to get it approved for use in patients with PMM2-HIPKD-IBD. With the assembloid laboratory model derived from patients, researchers can produce useful data to be used for clinical approval and speed up the process to get this new treatment to patients.

Co-author Dr Kelsey Jones, a consultant in paediatric gastroenterology at GOSH, said: “This is an important development towards a personalised treatment for patients with this rare and complicated genetic condition. It provides an example of how working with patients to understand the scientific basis of disease can lead to real benefits for them and their families.”

The research has been funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research GOSH Biomedical Research Centre, with contributions from the Oak Foundation and GOSH Charity. GOSH Charity will now support the direct continuation of this work – which will include the testing of repurposed drugs to treat PMM2-HIPKD-IBD.

Professor Marian Knight, scientific director for NIHR Infrastructure, said: "This innovative work using miniature stomachs showcases how researchers in NIHR infrastructure are driving the UK’s life sciences edge. Working with patients living with rare diseases has led to the discovery of potentially life-changing treatments. If this experimental approach can be used for other conditions, it will bring hope to many patients struggling to get the treatments they need."

Source: University College London

27.01.2026