Keeping everything under control in the ICU

During intensive care, hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance are widespread in diabetics as well as non-diabetics. However, whether the normalisation of blood glucose levels with insulin therapy improves the prognosis of such patients is still debated.

Karoline Laarmann reports

Adequate clinical studies and sufficient personnel resources to cover glucose monitoring and control in all hospital departments is missing, says Professor Christophe De Block, at the Department Endocrinology and Diabetology, University of Antwerp, Belgium. However, he believes that a strict glycaemic control does have beneficial effects on patient’s outcome.

The Leuven I Study in 2001 (van den Berghe et al), the first randomised trial on intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients, showed an improvement on the morbidity and mortality of surgical intensive care unit (ICU) patients, when blood glucose was maintained ≤ 110 mg/dl. In recent times, a couple of other studies refute that intensive glucose control reduces mortality. Instead, in the NICE-SUGAR trial (2009), for example, intensive glucose control in critically ill adult patients increased the number of hypoglycaemic events and even the mortality risk by 10%.

‘The conclusions of those current studies must be handled with caution,’ Prof. De Block advises. No decent study design has yet been designed that evaluates the outcome of strict glycaemic control over a long period of time, he points out. ‘Usually, strict glycaemic control is applied only during 3-5 day stay in ICUs or coronary care units, then the outcome is evaluated later, after 90 days – so no one knows what happens between day five and day 90. Therefore, it’s difficult to make a firm recommendation on an effective glucose control management.’

In this regard, another problem is that, while in the ICU, a patient’s blood sugar levels are monitored on a frequent basis, following transfer to a hospital ward, glucose monitoring loses priority. And, there are no trials investigating the influence of glucose control on patient groups moving from an ICU to a hospital ward. ‘Whereas, in the ICU one nurse tends two patients, in other departments three nurses take care of 20 patients,’ the professor points out. ‘Achieving strict glycaemic control requires extensive nursing efforts. A tight glucose control means that glycaemia has to be measured every two hours. The measuring itself takes 3-5 minutes. In other words, one hour a day would be reserved only for measuring glucose values and adapting insulin infusion.’

At Antwerp University Hospital, Prof. De Block and team have developed a peri-operative glucose management programme which takes three parameters into account:

● adoption of a safe target between 80 to 150 mg/dl

● a reliable administration route (preferred an Intravenous/IV Route)

● frequency of glucose monitoring.

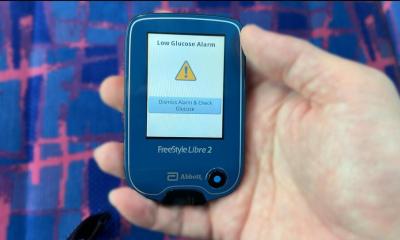

A strict protocol must be observed to achieve an adequate frequency of glucose measurement. Preferred are computer-driven glycaemic control protocols taking into account the actual glucose value, rate of insulin infusion, and also the rate of change (increase/decrease) of glycaemia. In recent years, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems have become available to measure interstitial glucose levels every five minutes, day and night.

In a 2010 study by Holzinger and colleagues showed that the use of real-time CGM technology reduced the number of hypoglycaemic events – the limiting factor to apply strict glucose control - significantly. ‘But, because these systems measure glucose levels of interstitial fluid, instead of in arterial or venous blood, they have to be correctly calibrated and interpreted with the necessary caution,’ Prof. De Block emphasises.

Thus, while it has been shown that continuous glucose monitoring technology can help to administer insulin infusion and avoid glucose variability, nonetheless the accuracy of CGM still must be improved. ‘Several international researchers are working on a proper algorithm to add to the technical CGM tool -- like our group, and the groups of Roman Hovorka, University of Cambridge, UK, Greet Van Den Berghe, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium, and Professor Thomas Pieber at the Medical University Graz, Austria.’

28.02.2011