Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Why ECMO? Why an airbag?

There is little evidence on respiratory support with extracorporeal systems – enough of an argument for most of those doubting the procedure not to use it, or even make it available.

However, the requested prospective, randomised – and ideally double-blind studies involving large numbers of patients – are unlikely ever to be carried out. And why should they? After all, no one ever requested these types of studies for air bag use – yet they are still being fitted.

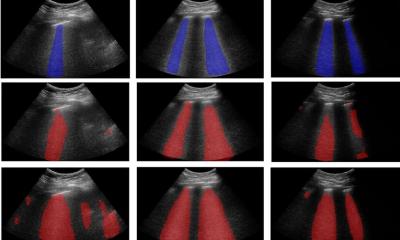

ECMO, i.e. extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, takes the strain off a patient’s own lungs for a few hours or days, and in exceptional cases even weeks, by supplying pre-oxygenated blood. A catheter is inserted into a hollow vein close to the heart and transports blood along a gas exchange membrane, filters out carbon dioxide and enriches it with oxygen and, most often powered through a centrifugal pump, transports it back to a venous vessel near the heart.

The procedure became possible through the development of the membrane lung by Dr Theodore Kolobow, and first used successfully in an adult in 1972 by Dr Donald Hill. Even the first large, prospective randomised study, published in 1979, appeared to point towards the end for this then relatively new type of treatment. Out of 90 adult patients with arterial hypoxia, 48 were exclusively treated with mechanical ventilation and 42 patients additionally with veno-arterial ECMO. In both groups, four patients survived (8.3% vs. 9.5%). Due to the lack of survival benefit patient recruitment for the study stopped early. ‘ECMO can support respiratory gas exchange but did not increase the probability of long-term survival in patients with severe acute respiratory failure,’ the authors concluded [JAMA. 1979 Nov 16;242(20):2193-6].

However, ECMO therapy for infants is different. First successfully used in 1975 by Dr Robert Bartlett, in 1991 the Extracorporeal Life Support Organisation (ELSO) reported that out of 3,528 infants with predicted mortality of 83%, 80% in fact survived thanks to ECMO.

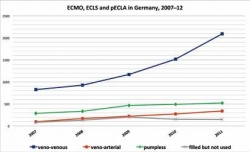

The lack of real options to treat acute, progressive lung failure on the one hand and advances in membrane technology on the other, have continued to maintain interest in ECMO. Continuously increasing cases leave us with no choice. Consider the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 and 2010, with talk of 18,500 dead worldwide. Epidemiologists now estimate there were in fact 284,500 victims, 80% of them aged under 65 and 51% in Southeast Asia and Africa [Lancet Infect Dis. 2012 Sep;12(9):687-95].

At the time, researchers from Australia and New Zealand collected data on frequency, clinical characteristics, complications and survival of patients with severe influenza-associated ARDS. 15 out of 187 intensive care wards treated 68 patients with ECMO. The average age was 34.4 years, the length of ECMO support a median of 10 days, and mortality was 21% [JAMA 2009 Nov 4;302(17):1888-1895]. Sceptics view the fact that these patients cannot be compared to those who – being less severely ill – were not given ECMO, as further proof of a lack of evidence. They also similarly view the results of the CESAR trials published in 2009. Out of 790 patients examined, 180 were admitted and randomised 1:1. 90 patients were to receive conventional treatment, the other 90 via ECMO. Ultimately 68 patients (75%) were given ECMO, 57 (63%) were still alive after six months – compared to 41 out of 87 (47%) in the conventional group [Lancet. 2009 Oct 17;374(9698):1351-6]. Although this result is significant, with a relative risk of 0.69, a 95% confidence interval of 0.05-0.97 and p=0.03, critics claim that only one patient made the difference between a significant and non-significant result.

So, what would help to convince the critics? Maybe take a look at medical history. All it took to establish vitamin C as a valid treatment of scurvy among sailors were a few lemons, a keen eye and conviction. Nobody then had the idea to randomise sailing crews before they set off on months-long journeys. Or let’s take a trip in the car: Nobody these days would seriously request that only every other new car should be fitted with airbags and then to check, a year on, in which group more passengers survived accidents…

26.04.2013