Teamwork

Emergency ultrasound

Resuscitation is always a desperate attempt by an entire team to save a human life. If a reversible cause can be discovered, a patient’s chances of survival increase considerably. All medics therefore know the ‘4 Hs’ and ‘HITS’.

Report: Brigitte Dinkloh

Imagine you had a diagnostic tool that could either confirm or exclude four of these very quickly. Wouldn’t this be fantastic?

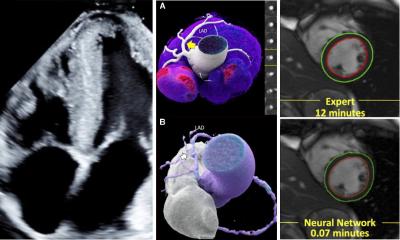

Actually, it’s not so much a case of ‘wouldn’t it’ but ‘isn’t it’. With the help of emergency ultrasound, a cardiac tamponade can be diagnosed or excluded at a glance. Modern ultrasound technology also facilitates the mobile use of devices beyond the hospital. Suitable ultrasound scanners are driven, or flown respectively, to accident scenes in ambulances and helicopters.

Eberhard Reithmeier MD, a consultant in the Department of Anaesthetics and Intensive Care at the Regional Hospital in Feldkirch, Austria, has worked with emergency ultrasound for years.

‘This diagnostic discipline brings together radiologists, internists, surgeons and anaesthetists who carry out standardised examinations and “speak the same language”, ‘despite their different backgrounds,’ he says. ‘In this, and for training, interdisciplinary cooperation is at the forefront.’

Ruling out cardiac tamponade

Emergency ultrasound is, for example, used when doctors are looking for the cause of hypotension in a patient. Is the heart not working sufficiently? Is the patient dehydrated? Is it a case of tension pneumothorax?

‘You don’t have to be a cardiologist to see that the left ventricle is beating empty, Dr Rathmeier points out. ‘If this is the case, we rescan the inferior vena cava .and will see that this collapses breath-synchronously.’

In this situation, a lack of volume can quickly be differentiated from acute heart failure. A pneumothorax as well as acute right ventricular strain can also be diagnosed with precision.

One of the advantages is the availability of imaging diagnostics in locations with no CT scanner. ‘This has mainly become possible because of ever smaller and cheaper devices,’ says Reithmeier. The scanners are now available from about €8,000 and, thanks to their dimensions, range from real ‘handhelds’ to laptop size, so are also suitable for preclinical use. ‘In a few years I think it will be the norm to have these devices in all ambulances,’ he believes. ‘Currently, it’s down to lobbying by individuals for this type of investment from the respective emergency medical service providers.’

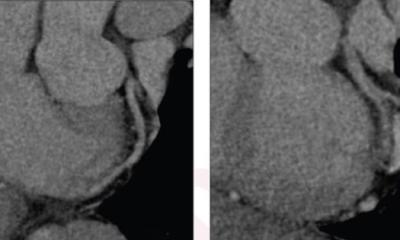

It is up to each individual hospital how ultrasound and CT are used in the shock room. Ultrasound has an important advantage when it comes to the examination of haemodynamically unstable patients. The significantly faster E-Fast examination can confirm the presence of free fluid in the abdomen. Many shock room algorithms then point the way directly into the operating theatre with the need to carry out a CT scan.

However, the consultant does not believe that ultrasound is in competition with CT scanning for the majority of patients in the shock room who are haemodynamically stable. ‘The current S3 guideline on polytrauma/treatment of patients with severe and multiple traumatic injuries illustrates the problem very well.’

In the intensive care unit (ICU) things look very different: ‘We’ve seen that emergency ultrasound in the ICU can considerably reduce the number of chest X-rays and also the number of CT scans required. Why should I expose a patient to unnecessary radiation when there is an equally good, or even better, and definitely faster procedure available without radiation?’

The fact that emergency ultrasound has an important place on the intensive care ward is now an accepted standard and has therefore become part of teaching. ‘A specialist in intensive care must be able to diagnose a pulmonary oedema on an ultrasound scan if he wants to be awarded the European Diploma in Intensive Care (EDIC). ‘This is now already part of the test,’ the anaesthetist and intensive care expert says.

Monitoring venous catheter insertion

The general rule is that interdisciplinary cooperation achieves the best results for the patient. During his time in Ulm, the radiologist undertook the ultrasound scanning in the shock room, but in Feldkirch it is in the hands of the surgeon or anaesthetist. ‘This is done simultaneously, while the other medics care for the patient based on the shock room ABC,’ he explains.

The insertion of central venous catheters is now almost exclusively carried out under ultrasound guidance. The first studies to confirm that the use of ultrasound for the insertion of venous catheters has advantages were published in the 1990s. ‘During the first years of my training the so-called landmark procedure was still being used. These days it’s almost always the ultrasound guided puncture that’s is being taught,’ Dr Reithmeir reflects.

A place in anaesthetics He is pleased that ultrasound also has its place within anaesthetics. ‘The entire field of local anaesthesia has been revolutionised by neuro-ultrasound. When nerves in the arms or legs are anaesthetised this is now almost always done with ultrasound guidance. It is quite something, even for experienced anaesthetists, when they see the needle approach the nerve ‘live’ for the first time, followed by the dispersal of the local anaesthetic around the nerve. Why wear a blindfold when you can see?’

Standardised training

As emergency ultrasound scans are performed by representatives of different medical disciplines training standards are needed to assure quality. There have always been calls for this. ‘A joint concept for emergency ultrasound covering three different countries was implemented in 2008,’ Reithmeier reports. ‘Experts from different countries and different medical disciplines came together and agreed on a joint concept, which resulted in a number of emergency ultrasound courses now being offered by the DEGUM, OEGUM and SGUM (Ultrasound in medicine societies in Germany, Austria and Switzerland).

Although not mandatory, there is growing interest in them, because training provides more assurance when scanning and, in times of an increasing need for documentation, training provides a level of support that should not be underestimated. The next important step for the near future will be to integrate these course contents into existing, internal clinical training systems and into specialist medical training.’

Profile:

Eberhard Ernst Reithmeier MD a medical graduate and qualified anaesthetist from the University of Ulm, and, in 2005, he qualified as a specialist in accident and emergency care. In March 2014, he became an anaesthetics and intensive care consultant at the Regional Feldkirch Hospital, Austria, and he teaches ‘Ultrasound with a focus on Anaesthetics’ for the German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (DGAI).

25.10.2016