Easy breathe - new tools for prolonged lung support

Almost 40 years old, the idea of temporary lung assist device has reached a level where it works not only in anecdotal cases

Often a life-saving intervention, mechanical ventilation also has some serious drawbacks: the need for sedation, the risk of ventilator associated pneumonia, intubation or tracheostomy related complications. In 1972, Donald Hill from Pacific Medical Centre, Los Angeles, reported the first successful long-term mechanical lung assist device with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

After 75 hours of support of a 24-year-old multiple trauma patient with aortic rupture, the shock-lung syndrome was reversed and the patient recovered [Source: NEJM 286:629-634].

Three years later, a Mexican woman who believed her unborn child would have a better life in the USA, journeyed to Los Angeles. En route, when her membranes ruptured she arrived at Orange County Medical Centre. The child was born but her lungs could not supply enough oxygen. Despite turning up the ventilator to the highest settings, oxygen tension dropped to 12 mm of mercury.

Involved in developing the membrane lung, thoracic surgeon Robert Bartlett brought in a machine from the laboratory. About 150 severe respiratory failure patients had already been treated with the device; 10-15% survived. However, all were adults, not infants, not newborns. In a strict sense probably without informed consent, he explained what they were going to attempt. Without English and being illiterate, the mother signed with an X and disappeared, perhaps fearing her baby’s outcome as well as her own of deportation. After three days of bypass, Esperanza -- the name nurses gave the baby — completely recovered.

How ECMO works

Back then, three days of support was an incredible success. Today, a three-day treatment is likely to be regarded as short-term therapy. ECMO acts temporarily as a patient's lung while recovering from an underlying condition. After cannulation of the femoral or neck vessels, a portion of the patient's blood flows through to an extracorporeal membrane oxygenator, where carbon dioxide is removed and blood is oxygenated and then pumped back into the vascular system.

Cannulation, homeostasis and coagulation management are the critical points. Johannes Gehron, head perfusionist at the Justus Liebig University Hospital Giessen explained: ‘I must consider not only the current state but also the coming days. The patient interacts with the ECMO system. Any change in his clinical situation may result in ECMO adjustment for optimum performance, but currently there is no simple clinical measurement method to detect such a change.’

ECMO to pECLA

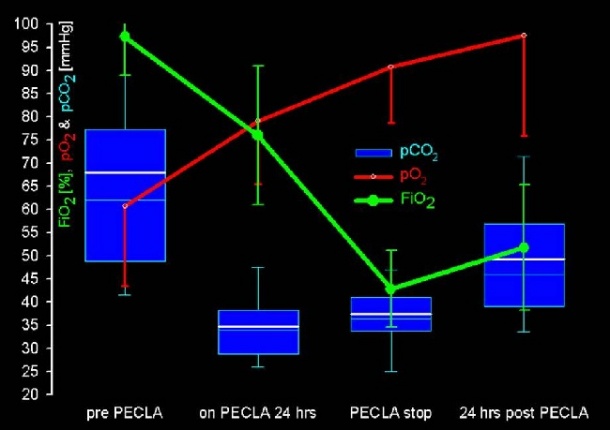

In 1996, a working group of perfusionists, intensivists and cardiac surgeons at the University Hospital Regensburg, developed a new method: the pumpless extracorporeal lung assist (pECLA) device, an arterio-venous bypass system without a pumping unit. The patient’s mean arterial pressure is responsible for blood flow through a low-resistance gas exchange module.

With the arteriovenous, pumpless mode, the extracorporeal blood flow is limited; as a result, oxygenation capacity from extracorporeal gas exchange is lower compared to venovenous ECLA employing higher blood flows. For that reason, pECLA focuses on treatment of predominately hypercapnic patients. The use of a smaller cannula for arterial access (13-15Fr) allows appropriate blood flows to decarboxylate the blood.

‘The procedure is reserved for patients without severe functional impairment of cardiac pump function,’ explained Alois Philipp, one of the inventors and chief perfusionist at the Regensburg University Hospital. For pumpless use, the mean arterial blood pressure should at least be 60mmHg. Due to a lower risk of bleeding and the associated decrease in transfusion requirements, patients with abnormal clotting particularly profit from pump-free therapy. In principle, PECLA can be used in all forms of respiratory failure.

The iLA

Developed in cooperation with Jostra AG, this technology is currently sold as the iLA Mechanical Ventilator by Novalung GmbH, Heilbronn, and has two major indications: Pulmonary lung failure (i.e. ARDS) and breathing pump failure (i.e. exacerbated COPD). Depending on the clinical needs of the patient, and extracorporeal blood flows required to support gas exchange appropriately, the iLA can be used in pumpless, arteriovenous and pump driven venovenous modes within the approved ranges for blood flow of 0.5-4.5 L/min.

Dr Torsten Rinne, Medical Director at Novalung, said: ‘With arteriovenous use, nearly complete carbon dioxide removal is achieved at gentle flow rates in range of 0.8-1.5 L/min, allowing reduction of aggressive mechanical ventilation in ARDS patients. In acute hypercapnic lung failure, such as exacerbated COPD, the device is increasingly used to avoid intubation and to support spontaneous breathing. New technologies like the upcoming Novalung venovenous lung assist device will also aim to support the patient’s mobilisation better.’

Hemolung respiratory dialysis

Not yet on sale is the Hemolung, developed by Dr W J Federspiel, Professor of Chemical Engineering, Surgery and Bioengineering at the McGowan Institute of Regenerative Medicine, and founder of ALung Technologies, a Pittsburgh-based medical start-up company. The Hemolung is expected to allow patients in acute respiratory failure to avoid intubation and mechanical ventilation or, as an adjunct, shorten the time spent on the ventilator in an ICU. The dialysis-like system effectively supplements lung function through a single, 15-French small, double-lumen cannula, preferably inserted via jugular vein and removing up to 50% of retained carbon dioxide from the blood while administering up to 25% of oxygen.

A pilot study of the Hemolung device is currently underway in German clinics (including Essen, Goettingen and Bonn) to demonstrate the safety and performance of the device. Actually, 12 out of 20 patients are enrolled. A US-based pivotal trial to gain FDA clearance will follow. ‘We are very excited about the early results from our clinical trial in Germany,’ said Nicholas Kuhn, Chief Operating Officer at ALung. ‘We look forward to completing our clinical trial and introducing the Hemolung to physicians and patients in the near future.’

The time seems ripe for new devices: In Germany, for example, the number of ECMO rose from 719 in 2005 up to 2057 in 2009 – an increase of 286% in five years! How? Just before the rally started, the therapy was reimbursed in the DRG system. Depending on the hospital’s negotiating skills, an ECMO or ECLA generates revenue of €600 via €6,800 up to €32,000.

Another reason for the start-up companies’ hope: in 2010 the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) published the Conventional Ventilator Support versus ECMO for Severe Adult Respiratory Failure (CESAR) trial, the first randomised controlled trial with parallel economic evaluation. 180 patients (90 in each arm), aged 18–65 years with severe, but potentially reversible, respiratory failure, were randomised from 68 centres to either conventional management (CM) in referring hospitals throughout the UK, or to consideration of interventional treatment at the ECMO centre at Glenfield Hospital, Leicester. Of the 90 patients randomised to the ECMO arm, 68 received that treatment. In the ECMO arm, 33 of 90 patients (36.7%) died or were severely disabled six months after randomisation, compared with 46 of 87 (52.9%) in the CM arm [Source: Health Technology Assessment 2010; Vol.14: Nr.35]. This equated to one extra survivor for every six patients treated and is promising compared to the 10-15% survival rate at the early beginning in Orange County in the 1970s.

Text by: Holger Zorn

28.02.2011